Southeast Asia and the chip wars: Navigating a decoupling world

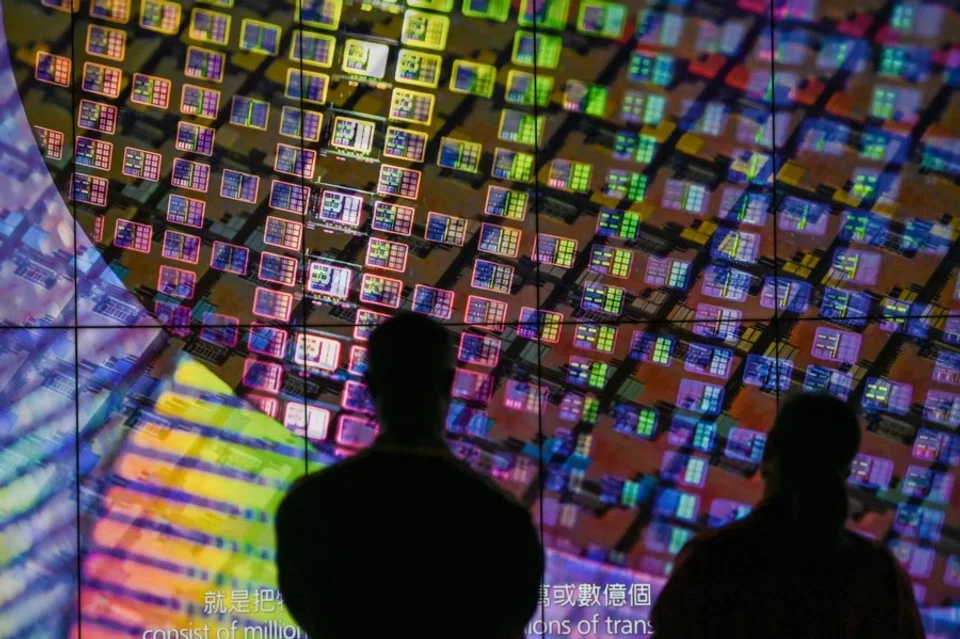

The race for some Southeast Asian countries to anchor themselves in the global semiconductor industry is open and evolving, even as it is complicated by factors like great power rivalry.

Global demand for microelectronics has boomed, even as US pressure on China has driven chip industry leaders to look elsewhere for their operations. The US, EU and Korean heavyweights in the semiconductor supply chain have turned to Southeast Asia to host a flood of new projects, with most going to Singapore, Malaysia and Vietnam.

Capturing higher value-add positions

Singapore and Malaysia established themselves in the then globalising chip supply chain in the 1960s-1970s. Vietnam is a relative latecomer but now offers greater scale and potential resources. Many of the latest projects in these countries (see table) are expansions of existing facilities with proven track records, leveraging the extant infrastructure and local workforce.

All three governments are focused on capturing higher value-add positions in the globalised chip industry. As the CEO of InvestPenang recently said, “To move out from the middle income trap… we have to move up the value chain (and away from) commoditised products.” To quote Singapore’s former minister for trade and industry, “We do not just want to provide support services (but also to) position ourselves at particular niches…that makes it hard for us to be displaced”.

This highlights how industry upgrading is key not just to growing incomes but also to economic security, in a world where states whose firms control these technologies are politicising their supply chain dominance and trying to reshore chip sector activity. However, this implies more intense competition within ASEAN and potentially diverging approaches towards US-China rivalry.

Singapore is still largely a technology taker, whose position in the global chip industry is linked to the presence of foreign multinationals.

Singapore aims to grow its manufacturing sector by 50% from 2021 to 2030 and has ambitious plans to be an artificial intelligence (AI) hub. Semiconductors are key to these goals and already account for almost half of Singapore’s manufacturing output and 7% of GDP. As the first ASEAN country to enter this industry, Singapore has a competitive R&D infrastructure and has been the preferred regional location for more complex activities. It remains globally competitive for advanced manufacturing, with front-end fabrication vendors conducting major expansions at their Singapore sites.

Despite this, Singapore is still largely a technology taker, whose position in the global chip industry is linked to the presence of foreign multinationals. Singapore has produced competitive companies in this sector but these are few and dependent on servicing foreign customers.

The government is clear that over the longer term, Singapore cannot compete in the subsidies arms race among the world’s largest economies to attract chip sector activity. Instead, as its then trade and industry minister said in 2021, Singapore must aspire to “create core intellectual property…to entrench…relevance…Without this, (Singapore) will just be one amongst many.”

... many Chinese companies setting up in Penang are components suppliers to US firms that can no longer source directly from China due to US export controls.

Focus on upgrading

A similar focus on upgrading within the global semiconductor supply chain is evident in Malaysia. Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim recently described moving into higher value-added chip manufacturing as “as a critical goal (and) a departure from our history”. His government’s New Industrial Master Plan 2030 aims to build chip design champions for electric vehicles and AI, and to attract advanced wafer fabrication and equipment manufacturing to Malaysia. Anwar’s international trade and industry minister heads a national semiconductor strategic task force aimed at attracting “strategic investment” to a sector that contributes almost half of Malaysia’s manufacturing export revenue.

The “endgame” for this evolution of Malaysia’s extant role in the chip supply chain — Malaysia already accounts for 13% of the global assembly, test, and packaging segment — includes a strong position in end user sectors like automotive. Many new chip projects aimed to serve electric vehicle (EV) production. Last year, Tesla established its regional headquarters in Malaysia. Chinese EV makers are also piling in, even as EVs emerge as the next front in the US-China technology wars.

Car chips are unlikely to be the only subject of international tensions, given the scale and range of foreign activity in Malaysia’s semiconductor sector. Reportedly, many Chinese companies setting up in Penang are components suppliers to US firms that can no longer source directly from China due to US export controls.

XFusion, a former Huawei subsidiary, is developing local production of graphics processing units (GPUs), a chip type that has been a primary focus of US export controls targeting China. There are also rumours of Chinese firms planning to bring to Malaysia advanced packaging technologies, which will likely soon attract new US controls. However, as in other fields like 5G telecommunications, the Malaysian government is not hitting the brakes: Anwar recently criticised “China-phobia” and made clear that Malaysia remains open to US and Chinese chip firms.

Human capital and infrastructure deficits

With its large and relatively youthful population, Vietnam is the semiconductor supply chain’s new frontier in Southeast Asia. Its government is prioritising the chip sector in economic planning and capitalising on foreign enthusiasm for alternative outsourcing locations. The 2023 visit by US President Joseph R. Biden was accompanied by announcements from US firms of local projects. Biden was followed shortly by Netherlands Prime Minister Mark Rutte, with Dutch companies announcing major investments.

However, Vietnam’s human capital and infrastructure deficits impose serious constraints on the local chip sector’s development. Electricity shortages, which forced multinationals to suspend production for several hours a day over weeks last year, are unlikely to be easily resolved. According to Vietnam’s science and technology minister, the nation’s semiconductor industry has a low localisation rate. Striking technology transfer deals with foreign industry leaders are necessary to maintain progress.

Southeast Asia’s expanding role in the global chip supply chain will complicate the politics of navigating US-China hostility, especially given the gap between the US government’s political goals and multinational companies’ choices. For example, the Biden administration is supporting the Philippines’ development of its chip sector, including with US federal funding. But this preference reflects Manila’s greater readiness to align with Washington against Beijing more than commercial and technical factors, which are leading US and European semiconductor firms to invest in Malaysia.

The quest in this demanding industry for scarce foreign investment and skilled labour will also drive zero-sum competition. Singaporean and Malaysian ministers express ambition for their respective countries to be the region’s “centre of innovation” or “the preferred digital hub”. Malaysia’s chief development bottleneck is the drain of skilled labour to Singapore, while Vietnam’s deficit of engineers to support its chip sector’s needs may approach the tens of thousands by 2030. The flow-on effects to end-user sectors will also create winners and losers within ASEAN.

This article was first published in Fulcrum, ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute’s blogsite.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)