Public awareness, perception and digital divide: Addressing the effectiveness of provisions on algorithm-generated recommendations in China

As governments across the world grapple with ways to regulate platform algorithms, China has pushed ahead with rolling out a set of provisions regulating algorithm-generated recommendations for internet information services. Chinese tech giants have taken prompt adaptive actions in response, but a lack of consumer awareness, prevailing attitudes and a digital divide may undermine the authorities' efforts.

With the rapid development of big data and artificial intelligence (AI), algorithm-generated recommendations are widely adopted for internet information services.

On the one hand, these personalised recommendations significantly save consumers' time and effort in exploring the vast digital marketplace. On the other hand, as highlighted by a group of US researchers, recommendations do not just "reflect" but also "shape" consumer preferences, with "the potential to fuel biases and affect sales in unexpected ways". A Chinese expert has also pointed out some side effects such as dissemination of misinformation and disinformation, infringement of user rights, and manipulation of public opinion.

China taking leap into regulating algorithm-generated recommendations

While data collection and management have progressively been regulated around the world, for instance, the EU's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), Singapore's Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA), and China's Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) and Data Security Law (DSL), the regulation of algorithm-generated recommendations remains relatively untouched. It is exciting to note that China has taken groundbreaking legislative action to do so.

In that regard, the Provisions on the Administration of Algorithm-Generated Recommendations for Internet Information Services (互联网信息服务算法推荐管理规定) came into force on 1 March 2022. The provisions provide a framework for regulating recommendation algorithms, including "applying generation and synthesis, personalised push, selection sort, search filtering, scheduling decision, and other algorithm technologies to provide information to users".

With the implementation of the provisions, prompt actions have been taken by the major tech giants:

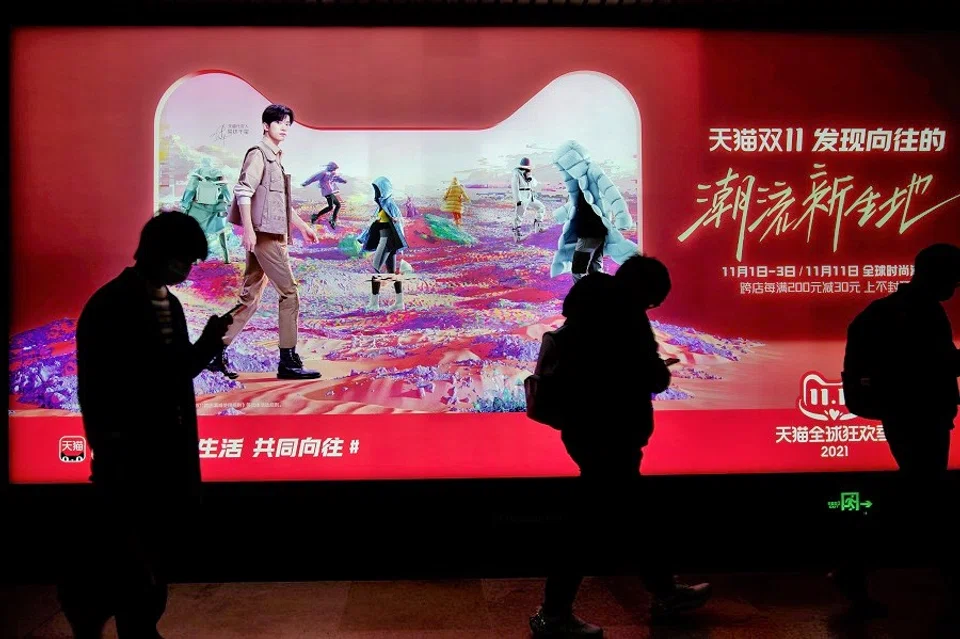

- Mainstream apps (e.g. Taobao, WeChat, Weibo and Douyin) have added buttons for users to turn off the personalised recommendation function.

- Some platforms (e.g. Taobao) now allow their users to view the list, times of collection, and use log of specific personal information as accessed by the apps.

- A few of them (e.g. Taobao, Baidu) provide users with an option to clear their previous activities (e.g. searching, browsing, purchasing, etc), or even labels as assigned by the recommendation algorithms.

However, with the tech giants' adaptive actions, is it enough to ensure the effectiveness of the legislation? Probably not.

Public awareness and perception

Internet consumers in China may not be aware of or appreciate this newly implemented regulation. They may not realise that their personal interests and rights have been infringed upon in terms of price discrimination, game addiction and induced consumption, simply by virtue of their online behaviours being captured, analysed, predicted and manipulated.

Likewise, they may not be aware that they can prevent this from happening by easily turning off the personalised recommendation function and clearing their previous activities as well as labels attached to them. It is very common for app developers to collect consumers' personal information by default, since most users would not read the "terms and conditions" carefully but just click the "agree" button immediately.

Moreover, as pointed out by Robin Li, the founder and CEO of Baidu, during the China Development Forum in 2018, "... Chinese are not so sensitive to privacy, and on most occasions, if they can, they are willing to sacrifice their privacy for convenience or efficiency." Li's statement triggered overwhelming criticism immediately. However, it also revealed a certain truth: for the general public in China, it seems that privacy is a tradeable value.

Similarly, a cross-country comparison study (China, Germany, UK and US) found that Chinese respondents seem to focus more on the beneficial aspects (e.g. convenience, efficiency) of facial recognition technology rather than the potential risks (e.g. privacy violation, discrimination and surveillance).

Granted, China netizens' awareness of rights protection is increasing, with personal data privacy being one of their concerns. However, when convenience, efficiency and/or financial benefits (e.g., member-exclusive discount, birthday voucher) are involved, privacy violation may no longer be their major concern.

As a result, tech giants in China can still take advantage of this trade-off by capturing consumers' personal data, processing them using AI algorithms and tailoring them to consumers' individual preferences to achieve their own goals.

Digital divide

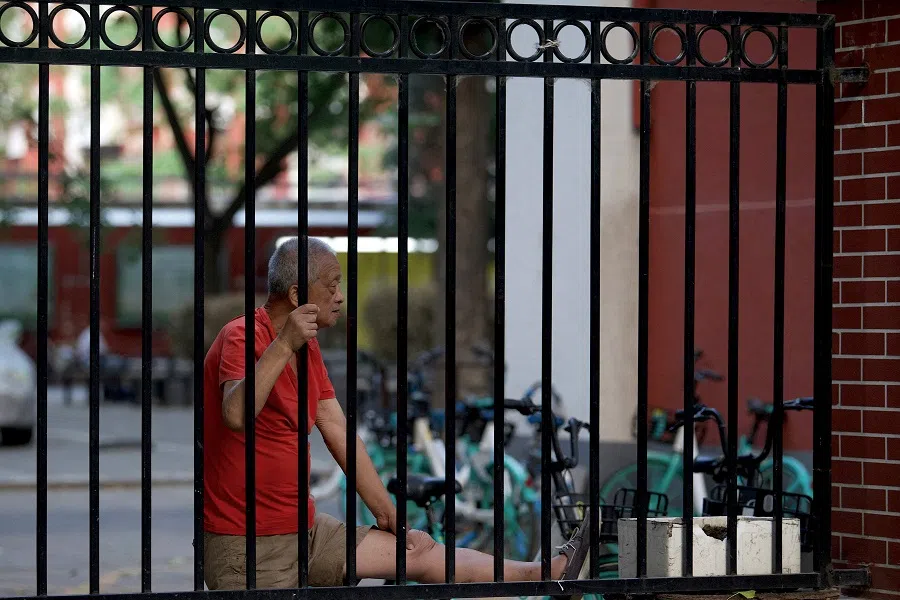

The digital divide could be another factor reducing the effectiveness of the provisions. According to the 49th Chinese Statistical Report on Internet Development by the China Internet Network Information Centre (CNNIC), as of December 2021, 43.2% of older adults aged 60 and above were internet users. This was far below the percentage of the whole population (73.0%). Also, the internet penetration rate for urban and rural regions was 81.3% and 57.6% respectively, with a gap of more than 20%.

A study of cases in China showed that the Covid-19 pandemic accelerated the pace of digital technology adoption but exacerbated the age-related digital divide.

The digital divide is no longer due to merely physical and material access to information communication technology (ICT), but the inequality of information, media skills, digital literacy, as well as usage. The ability to access, evaluate, synthesise, and use information becomes more critical.

Recent literature also suggests that the digital divide can influence "recognition and attainment of citizen's rights". Older adults, as comparatively less equipped with the knowledge and skills to properly surf the internet, are less likely to be concerned about the importance of personal information and the need to protect it.

Moreover, they may not be "tech-savvy" enough to navigate the interface of the apps to find the "hidden" button to opt themselves out for personalised recommendations, since by default, they have opted in.

In conclusion, it is noteworthy that China has taken some pioneering legislative action to regulate recommendation algorithms for internet information services, and the major tech giants have adjusted their operations accordingly. To further ensure the effectiveness of this legislation, additional steps should be taken to increase public awareness of privacy protection, as well as to address the digital divide by improving the digital and information literacy of the marginalised groups, so as to ensure information access and digital inclusion.

Related: China's burgeoning e-commerce cyberspace and its ever more complex regulations | Huawei senior executive: Trust matters in the post-pandemic digital age | How China's health code app permeates daily life and may still play a role post-Covid | A Singaporean in China: Contact tracing lays bare the lives of ordinary Chinese