Why Beijing thinks Nvidia’s H20 chip could be a spy tool

China’s investigation into Nvidia’s H20 chip reflects the growing geopolitical risk in semiconductors — where export policies, rare‑earth ties, and strategic control now define the global tech race. Technology industry professional Akhmad Hanan gives his take.

On 31 July 2025, China’s Cyberspace Administration (CAC) raised concerns that Nvidia’s H20 AI chip might contain a “backdoor” risking user data. The agency summoned Nvidia for an official explanation, requesting technical documentation.

This move came after a US proposal in May 2025 by Senator Tom Cotton, urging that exported chips be equipped with location-tracking functions to ensure their usage does not exceed permitted boundaries. For China, this is not merely a technical issue but part of the intensifying US-China technology competition.

Security concerns

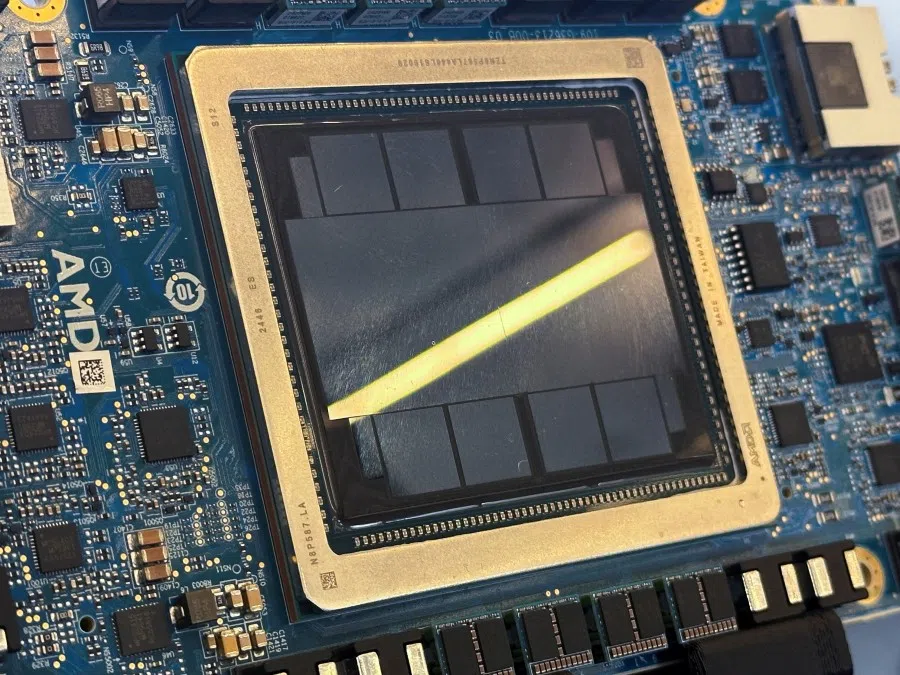

The H20 chip was designed by Nvidia specifically for the Chinese market to comply with US export restrictions first imposed in 2022 and tightened in 2023. In April 2025, the US banned H20 sales to China, causing Nvidia to incur US$5.5 billion in losses from unsold inventory and cancelled contracts.

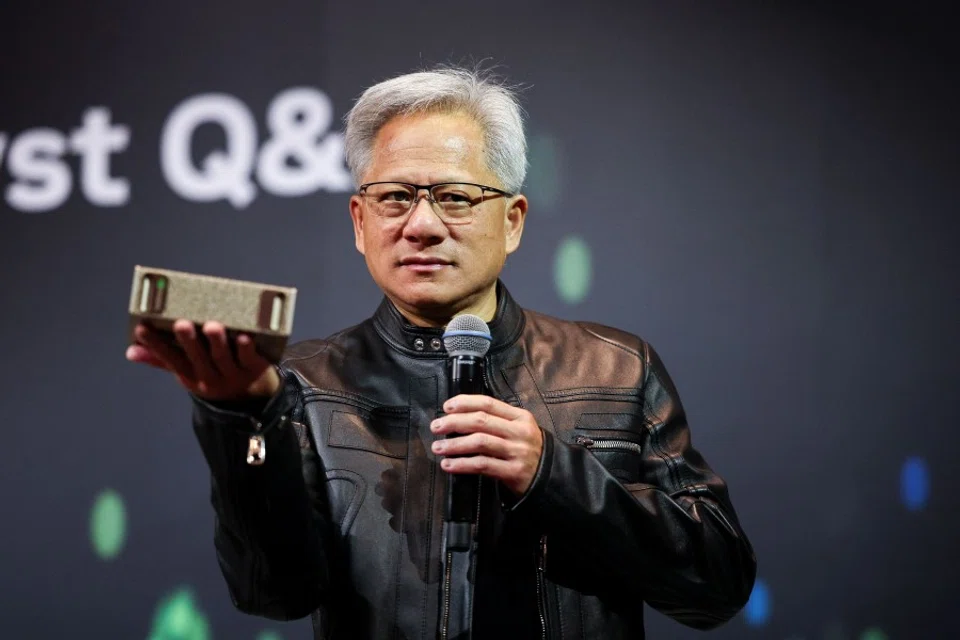

However, in July 2025, the ban was lifted after negotiations linked to rare mineral access, and the US subsequently granted licenses to Nvidia to export the H20 chip to China, reportedly following a meeting between Nvidia’s CEO Jensen Huang and US President Donald Trump. This enabled Nvidia to order 300,000 H20 units from TSMC to meet surging demand from Chinese technology firms, universities, and research institutions.

Just weeks after the ban reversal, CAC launched its investigation into the H20 chip, citing potential backdoor security risks that could enable surveillance. The US proposal to integrate location-tracking functions into chips has fueled Beijing’s suspicion that the technology could be used to monitor Chinese AI research and military applications.

China remains dependent on Nvidia chips for AI research and domestic applications, as local technology like the Ascend 910D cannot yet match the H20’s performance.

This is not China’s first assertive move against American tech firms. In 2023, Micron Technology was banned from supplying chips for critical infrastructure due to cybersecurity concerns. In 2024, the Cybersecurity Association of China called for a review of Intel products, although no formal action followed.

Since December 2024, Nvidia has also faced an antitrust investigation by the State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR) over its 2020 Mellanox acquisition, allegedly breaching commitments to fair technology access in China. These patterns reflect China’s strategy to limit US tech influence while promoting local solutions such as Huawei’s Ascend 910D chip.

Still, to what extent are China’s security concerns substantive? Analysts like Charlie Chai from 86Research suggest the move is likely symbolic. China remains dependent on Nvidia chips for AI research and domestic applications, as local technology like the Ascend 910D cannot yet match the H20’s performance. The 300,000-unit H20 order highlights this dependence.

Behind the symbolism, however, China is accelerating its drive to build a self-sufficient technology ecosystem. Through initiatives such as Made in China 2025 and massive semiconductor investments, Beijing seeks to reduce reliance on foreign technology. By pressuring Nvidia, China is not only signalling firmness toward the US but also reinforcing its domestic narrative of technological sovereignty.

Impact of H20 ban

The economic impact of this tension is significant. The earlier export ban on H20 caused major losses for Nvidia, while its reversal triggered a surge in demand that bolstered TSMC’s role as the key supplier. China’s new scrutiny could disrupt global supply chains and raise chip costs, with 2024 disruptions already adding US$200 billion to the tech industry, according to the Semiconductor Industry Association.

If China tightens regulations on Nvidia, companies like Huawei may capture market opportunities, though their production capacity remains limited. Meanwhile, global consumers — especially in developing countries — face the risk of higher electronics prices due to constrained chip supplies.

This tension also affects global AI innovation. Restricting access to advanced chips like H20 could slow AI development in China, but simultaneously encourage local diversification. Huawei, for instance, has increased its AI chip investments to reduce reliance on Nvidia, with the Ascend 910D being adopted in domestic data centres and cloud computing applications.

These countries could facilitate multilateral dialogues to establish neutral technology standards and reduce US-China tension. Yet, they also risk entanglement if the two superpowers deepen technological protectionism.

However, local technology limitations may hinder progress in areas like large-scale machine learning, which require the high performance that H20 or newer chips offer. It was reported that Chinese AI company DeepSeek delayed the release of its new model after being unable to train it using Huawei chips.

Conversely, the US also faces risks, as export restrictions may push China to accelerate independent innovation, potentially eroding long-term American tech dominance.

Role of third-party countries

The role of third-party countries is increasingly relevant. Taiwan, South Korea, and the European Union have major stakes in the semiconductor industry and could act as balancing forces.

Taiwan, via TSMC, is central to H20 production, while South Korea, through Samsung and SK Hynix, competes for greater market share. The EU, via the European Chips Act, has committed €43 billion (US$50 billion) to strengthen domestic semiconductor production.

These countries could facilitate multilateral dialogues to establish neutral technology standards and reduce US-China tension. Yet, they also risk entanglement if the two superpowers deepen technological protectionism.

‘Shadow technology’ and fragmentation

On the other hand, US policy shows clear contradictions. Congressmen like John Moolenaar oppose H20 sales to China, citing concerns that the chip could enhance Chinese AI capabilities, including military use. Yet, the July 2025 export ban reversal reflects Washington’s reliance on Chinese-controlled rare earths such as gallium and germanium.

The location-tracking proposal, though intended for strategic control, only heightened Beijing’s suspicions and complicated Nvidia’s position. With 13% of its revenue — approximately US$17 billion — coming from China, Nvidia is highly exposed to pressure from both sides.

Nvidia faces the dual challenge of complying with US regulations while safeguarding its vital Chinese market, and the world risks a fragmented technology ecosystem as cross-border semiconductor collaboration falters under rising protectionism.

A neutral analysis highlights the emergence of “shadow technology”, referring to parallel tech ecosystems developed under geopolitical pressure. In China, Huawei’s Ascend 910D illustrates this trajectory, while in the US, companies like AMD and Intel could create China-specific chips to fill gaps left by Nvidia.

This phenomenon risks fragmenting the global semiconductor market, reducing interoperability that has long underpinned innovation. Data shows China’s semiconductor investment rose 40% in 2024, while the US allocated US$52 billion under the CHIPS Act to boost domestic production. Such fragmentation may raise innovation costs and reduce global efficiency, as firms are forced to develop market-specific products.

The long-term implications are significant: Nvidia faces the dual challenge of complying with US regulations while safeguarding its vital Chinese market, and the world risks a fragmented technology ecosystem as cross-border semiconductor collaboration falters under rising protectionism. Countries like Taiwan and South Korea, dependent on global supply chains, could struggle to access cutting-edge technology, while consumers worldwide may face higher chip prices and limited supply.

Strategic tools in global power contest

Avoiding this outcome requires multilateral dialogue led by neutral actors such as the EU or ASEAN, the establishment of transparent security standards, and fair trade mechanisms under institutions like the WTO.

Ultimately, the H20 chip case highlights that semiconductors have evolved beyond pure innovation to become strategic tools in the contest for global power. The latest US licensing approval and revenue-sharing requirement signal a shift from outright export bans to controlled, profit-sharing arrangements, adding another dimension to the US-China technology rivalry.

In addition to the licensing decision, the US government now requires Nvidia and AMD to pay 15% of their China chip sales revenues to Washington. This revenue-sharing mandate could significantly impact Nvidia’s profit margins from its Chinese market operations and may prompt adjustments in pricing strategies or sales volumes.

Such a policy also underscores Washington’s intent to exert ongoing economic leverage over US tech firms operating in China, turning market access into a strategic bargaining tool.