Why China’s Covid expert won’t let AI take the lead

While AI is a powerful tool, China’s Covid expert Zhang Wenhong warns it cannot replace doctors. Academic Zhang Tiankan explains why hands-on experience, intuition and human judgment remain crucial.

The entry of artificial intelligence into all industries has become an inevitable trend of the times. A commonly accepted saying goes: AI will not replace you, but people who use AI may.

This means that AI may eliminate large numbers of people; those who do not master, embrace and use AI will inevitably be phased out — it is just a question of when. An article published in the British journal Nature offers some evidence of this, though limited to the field of scientific research. Researchers found that scientists who embrace any form of AI — from early machine-learning methods to today’s large language models — have consistently made the greatest progress in their careers. Compared with peers who do not use AI, scientists who adopt AI publish three times as many papers, receive five times as many citations and reach leadership positions more quickly.

However, not everyone agrees, especially authoritative figures in the medical profession.

... if a doctor, from the internship stage onward, bypasses complete training in diagnostic thinking and directly relies on AI to reach conclusions, the doctor will be unable to judge whether AI diagnoses are correct, and will also struggle to treat complex or difficult cases that AI cannot handle. — Professor Zhang Wenhong, Director, China’s National Center for Infectious Diseases (Shanghai)

Risks to clinical judgement

At the GASA 10th Anniversary Forum held in Hong Kong on 10 January, Professor Zhang Wenhong, director of China’s National Center for Infectious Diseases (Shanghai), clearly opposed the systematic introduction of AI into hospitals’ routine diagnostic and treatment workflows. He reasons that if a doctor, from the internship stage onward, bypasses complete training in diagnostic thinking and directly relies on AI to reach conclusions, the doctor will be unable to judge whether AI diagnoses are correct, and will also struggle to treat complex or difficult cases that AI cannot handle. This loss of capability is a deep-seated, hidden risk behind technological convenience.

Zhang’s concern about comprehensively and systematically introducing AI into routine hospital diagnosis and treatment is not without justification. In essence, fully trusting AI may be worse than not using AI at all.

AI has its limitations, and medicine has its own special characteristics. Relying on AI for convenience and speed will not only prevent doctors from receiving genuine clinical skills training and acquiring real diagnostic experience, but more importantly, AI may mislead doctors, resulting in misdiagnosis and overtreatment.

No one questions that AI can process and analyse vast amounts of data far beyond human capability. Yet if the data it relies on is incomplete or biased, even a small error at the start can lead to conclusions that are drastically off target.

... each hospital’s AI has its own limitations, and in effect constitutes a form of AI information silo.

Data-sharing barriers in Chinese hospitals

In reality, medical big data differs and is limited not only across countries and regions, but even among hospitals within the same country, as data is not shared. The data that AI software can typically collect comes from publicly published papers and books. Such data are not only outdated but also limited. Because of intellectual property considerations, not all hospitals, institutions, and medical professionals convert their diagnostic experience and skills into published papers.

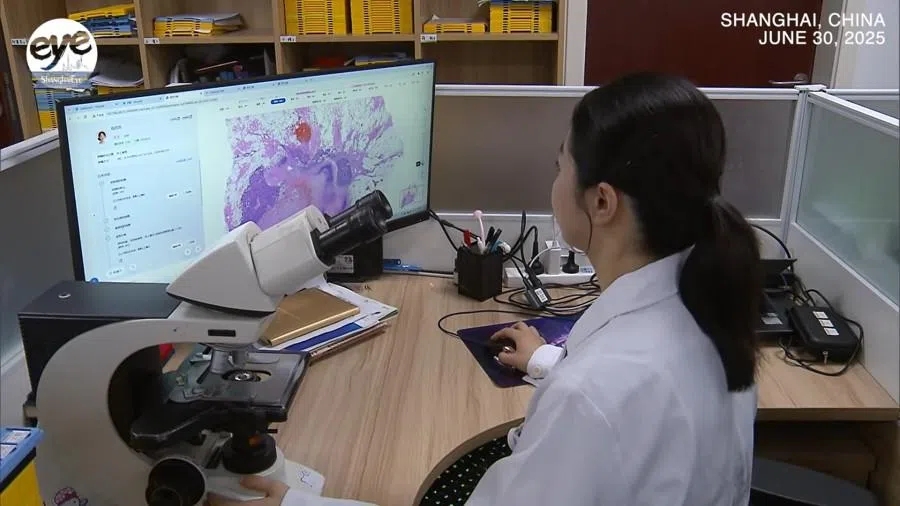

Yet the most practically useful data in clinical settings are patients’ medical records and diagnoses. Under the current medical system, these are siloed and difficult to share. Today, although China’s top-tier (Grade A tertiary) hospitals claim an AI technology coverage rate of 92.6%, this mostly refers to AI software developed from each hospital’s own data, such as Beijing Tiantan Hospital’s Longying model, Fudan Zhongshan Hospital’s chest imaging software that allows for multiple checks with a single scan, and the large model RuiPath at Ruijin Hospital. These systems range from image recognition to medical record generation and auxiliary diagnosis. The National Health Commission has also required full AI-assisted diagnostic coverage in tertiary hospitals by 2030. Nevertheless, each hospital’s AI has its own limitations, and in effect constitutes a form of AI information silo.

The reason is straightforward: hospitals in China have little incentive to share data with AI systems, primarily due to intellectual property concerns. They ask themselves why they should provide data to AI companies, research institutions or government agencies for software development — and if such software succeeds, who benefits from the profits? Patient privacy adds another layer of caution, as any breach could trigger complex, costly legal challenges.

In reality, enormous data barriers exist both within and between hospitals. Because of these barriers, current AI databases are naturally limited, which in turn leads to potential errors and inaccuracies when relying on AI.

The management of AI software is closely linked to questions of development, oversight and accountability. Following the principle that authority should match responsibility, hospitals are reluctant to share all their data. In many cases, doctors can only access information collected within their own departments, with data from other units remaining restricted.

In reality, enormous data barriers exist both within and between hospitals. Because of these barriers, current AI databases are naturally limited, which in turn leads to potential errors and inaccuracies when relying on AI.

AI cannot replace hands-on clinical judgement

Even if AI-based diagnoses have a certain degree of credibility, the special nature of medicine means it cannot rely entirely on AI, because clinical practice requires direct observation, hands-on examination and actual surgical intervention. Practical clinical skills include many aspects, such as observing patients’ language, tone, and posture, as well as applying palpation and percussion.

Take pain differentiation as an example: rebound tenderness (common in acute appendicitis), colicky pain (common in gallstones or kidney stones), distending pain (common in intestinal obstruction or gastritis) and dull pain (such as in hepatitis) all require doctors’ hands-on examination (palpation) and accumulated experience. These most basic competencies are things AI cannot provide.

Even if AI can judge diseases based on descriptions of pain, it cannot convey patients’ painful expressions, body language or inner experiences when symptoms occur. Only through clinical contact can doctors gain real experience and perception, which then rise to intuition and theory.

Doctors, by contrast, combine clinical experience with reasoning and intuition — a uniquely human capability that AI cannot replicate.

Experience and intuition remain irreplaceable

AI has clear limitations. It depends on historical data and struggles to handle new diseases or patients with unusual conditions. While AI excels at identifying statistical patterns, it cannot grasp causality or logical relationships. It can analyse data, but it cannot be physically present in the clinic to observe patients’ posture, expressions, or suffering. Doctors, by contrast, combine clinical experience with reasoning and intuition — a uniquely human capability that AI cannot replicate.

Even the da Vinci surgical robot, which performs AI- and robot-assisted surgery with greater precision, faster operation, and endurance for long procedures, still requires human operation, whether in direct manipulation or remote real-time control.

When doctors, particularly those early in their careers, rely solely on AI-generated diagnoses and treatment plans, they risk losing a holistic understanding of diseases and the medical process, along with the hands-on experience and skills gained through trial and error. It is like learning to drive: if someone never personally grips the steering wheel or operates the pedals, relying entirely on autonomous driving software, they will never truly feel how the vehicle responds, handle emergencies or become a competent driver.

By combining AI’s insights with human experience, intuition and hands-on skills, doctors can ensure accurate diagnoses and craft truly individualised treatment plans — preserving the uniquely human heart of medicine.

Moreover, when AI automatically generates medical records, provides diagnoses and recommends treatment plans, doctors may fall into a comfort zone of full acceptance, no longer asking “why” or “what”, but simply following AI’s recommendations. This can lead to “AI bias”. Going further, when AI fail to diagnose a disease, doctors who rely entirely on AI will be left helpless.

In practice, medicine is not as some imagine — where doctors can freely feed their expertise into AI, which then generates vast datasets to treat all diseases while humans focus solely on innovation. Even the most advanced AI software cannot perform real clinical operations. This limitation reflects the unique nature of medicine and explains why it can never rely entirely on AI.

AI has an important role in modern medicine, but only as an assistant, not a replacement. It can analyse cases, flag patterns and suggest diagnoses, but the final judgement must rest with doctors, who directly examine patients and interpret tests. By combining AI’s insights with human experience, intuition and hands-on skills, doctors can ensure accurate diagnoses and craft truly individualised treatment plans — preserving the uniquely human heart of medicine.