When the arts is more than politics: Reflections on the 50th anniversary of the Philadelphia Orchestra's China tour

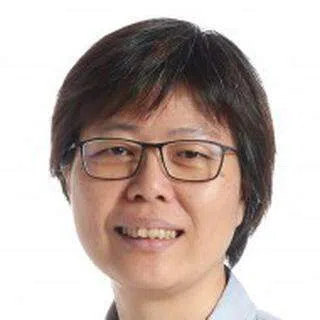

Learning of a recent performance in the US by Suzhou musicians, SPH Chinese Media Group editor-in-chief Lee Huay Leng muses on the role that the Philadelphia Orchestra's visit to Beijing had played in US-China relations in the 1970s. While no substitute for hard diplomacy, cultural exchanges can sow seeds of friendship among different peoples, and help the world reap something beautiful in the future.

At the start of the year, a group of Suzhou friends came to Singapore after visiting the US. Over a meal, as they talked about their US trip, I learned that they had been performing in Philadelphia and New York City.

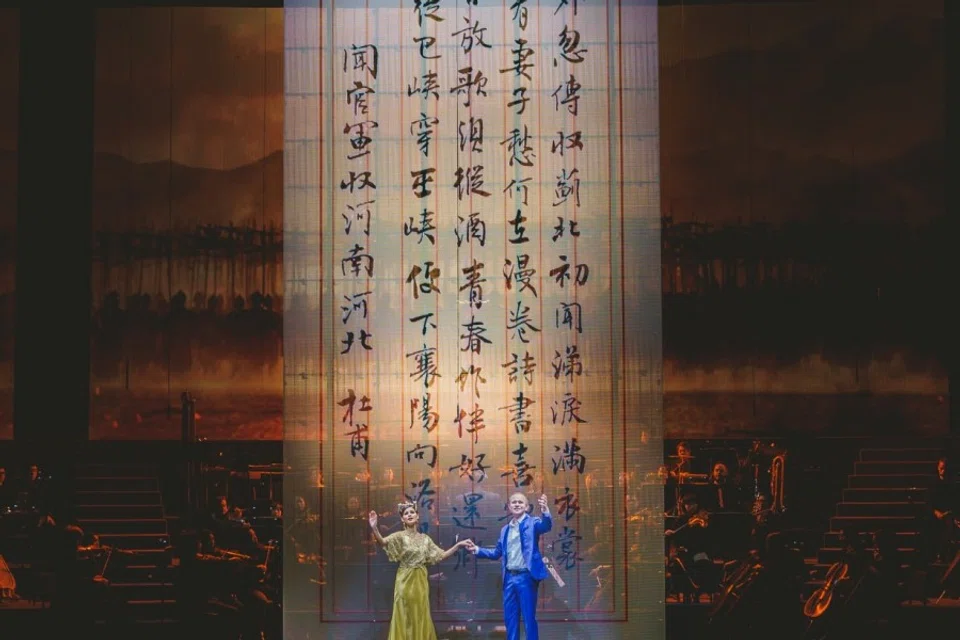

Since 2014, Suzhou has been hosting the iSING! Suzhou International Young Singers Art Festival, attracting young singers from all over the world to spread culture and the arts. This year, six young composers from different countries set melodies to Tang poems like Thoughts on a Quiet Night (《静夜思》) and Invitation to Drink (《将进酒》) by Li Bai, Farewell in the Grassland (《赋得古原草送别》) by Bai Juyi, and Ode to a Goose by Luo Binwang, with 15 singers from 10 countries performing in Chinese, accompanied by the Philadelphia Orchestra.

The performance, held in the first half of January, was called Echoes of Ancient Tang Poems. Jin Jie, member of the Standing Committee of the Suzhou Municipal Party Committee and director of the publicity department, led a group that performed at Kimmel Center in Philadelphia and Lincoln Center in New York City.

Why Philadelphia? My friend said the Philadelphia Orchestra toured China in 1973 as the first US orchestra to visit China, and so this was a Chinese New Year performance and a commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the orchestra's China tour.

Then Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai invited the Philadelphia Orchestra on a performing tour of Beijing, presumably after much thought and meticulous planning.

From 'ping pong diplomacy' to music diplomacy

Following the "ping pong diplomacy" of April 1971, then national security adviser Henry Kissinger went on a secret trip to Beijing in July, to prepare for President Richard Nixon's visit to China in 1972. In mid-1973, the US men's and women's basketball teams also visited China; in September that year, it was the Philadelphia Orchestra's turn to visit, in a show of music diplomacy.

Philadelphia was the first capital of the US following its independence, and the Philadelphia Orchestra was and is one of the Big Five orchestras in the US. Then Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai invited the Philadelphia Orchestra on a performing tour of Beijing, presumably after much thought and meticulous planning. Conducting the orchestra was 73-year-old Hungarian-born American Eugene Ormandy, who in the 1940s gave charity concerts in support of Canadian surgeon Dr Norman Bethune and his medical efforts for the Eighth Route Army.

Chinese consul-general in New York Huang Ping, Representative Dwight Evans and Philadelphia mayor Jim Kenney attended the performance of Echoes of Ancient Tang Poems. Reports quoted Huang as saying that "people-to-people exchange is a constant driving force for China-US relations".

We probably still recall that in early January, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) still required a negative Covid test within 48 hours for travellers from China, which made human movement a little inconvenient for cultural exchange. However, my Suzhou friends said that everything went smoothly at US Customs, and they got a warm reception from the audiences in Philadelphia and New York City.

I watched some online videos of the concert, and the atmosphere really seemed pretty good.

With this as a starting point, I did a search and found the book Beethoven in Beijing: Stories from the Philadelphia Orchestra's Historic Journey to China by US journalist Jennifer Lin, and the documentary of the same name, also directed by Lin along with co-director Sharon Mullally. This film is available to view on its website with a PBS account or through a one-time purchase, and in videos showing Lin at forums or giving keynote speeches, she said that through interviews and gathering information, she wanted to show China's interest in Western classical music, and record this chapter of history in 1973.

The beautiful music of the Philadelphia Orchestra changed his mind - he no longer wanted to be an "Eastern shaman" but a "Western shaman": a conductor of a Western orchestra.

Chinese-American composer Tan Dun has also spoken about the Philadelphia Orchestra's visit in the 70s. During the Cultural Revolution, the young Tan was "sent down" to Hunan, when one day while out in the fields he heard music through a loudspeaker. A friend asked him if he wanted to hear some interesting music and told him that it was called a "symphony", and the Philadelphia Orchestra was in China right then.

Tan said that was the first time he heard a "symphony", and in that autumn of 1973, he was deeply moved by the music coming out of the loudspeaker. He said during the Cultural Revolution he was the shaman (wizard) in his rural high school, conducting the band at weddings and funerals. The beautiful music of the Philadelphia Orchestra changed his mind - he no longer wanted to be an "Eastern shaman" but a "Western shaman": a conductor of a Western orchestra.

Another Chinese conductor Cai Jindong, a former professor of performance at Stanford University and now director of the US-China Music Institute and professor of music and arts at Bard College, recalled at a seminar that he was still young when the Philadelphia Orchestra visited China in 1973. Although they could still learn to play musical instruments during the Cultural Revolution, only revolutionary music could be performed. Initially learning the violin when he was in Beijing, Cai was very moved when he read news reports and saw photographs of the Philadelphia Orchestra's trip to China. Cai stressed that the trip was not just a piece of music news but a major event that society paid attention to.

The impact of music

After the Philadelphia Orchestra's four performances in Beijing in September 1973, the People's Daily published an article written by the "Morning Star of the Central Philharmonic" (央乐团晨星). It described the performance conducted by Eugene Ormandy as follows: "Their performance of Beethoven's Symphony No. 6 (Pastoral) brought the audience into picturesque scenes: clear streams and melodious birdsong; rustic and rudimentary village dances; gashes of rain and wind in lightning and thunder, followed suddenly by clear skies and lovely fields... With rich imagination and delicate sensibilities, Beethoven depicted the idyllic Vienna of the early 19th century and his state of mind as he strolled through the countryside.

"The orchestra's performance brought these scenes to life. Ormandy passionately conducted Beethoven's Symphony No. 5. The performance was rigorous, grand and passionate, especially in the transition from the third movement to the triumphant fourth movement, when emotions and musical intensity reached their peak. The orchestra gloriously performed a magnificent triumphal song, leaving the audience exhilarated."

The author ended the piece with: "On 16 September, Chinese and American musicians performed the Yellow River Piano Concerto together for the first time. The energetic and exhilarating piano performance was in harmony with the full and luxurious sound of the orchestra, deeply moving the audience. The successful collaboration between Chinese and American musicians illustrates the deep friendship between both countries."

In truth, a few months after the Philadelphia Orchestra performed in China, Beethoven was the target of criticism in the country.

While we may think that such articles are "nothing much" in today's context, it must have been difficult to publish such a detailed report of an outstanding orchestra performance of Beethoven's symphonies in the Chinese newspapers back then.

In truth, a few months after the Philadelphia Orchestra performed in China, Beethoven was the target of criticism in the country. I don't know what happened to this "Morning Star of the Central Philharmonic". At a time when Beethoven and symphony orchestras belonged to the bourgeoisie, and Beethoven's Symphony No. 5 (Fate) was considered to be advocating fatalism amid the Cultural Revolution, it is not difficult to imagine the plight of Chinese artists and how challenging it was to appreciate the arts.

In terms of impact, the Shanghai Communique released at the end of Nixon's visit to China is clearly more significant than the Philadelphia Orchestra's visit. However, in many cases, it is precisely amid ideological differences, national interests and the international political situation that sincere cultural exchanges among the masses become even more precious.

Indeed, if cultural exchanges do not take place at the right time or coincide with official expectations of warm bilateral relations, they may not happen. Even if cultural exchanges take place, years later, if the international situation and political discourse change, they may not even be remembered, much less influence the overall situation.

... the efforts of my Suzhou friends could be planting some new seeds.

Under such circumstances, they may just become an anniversary or an indicator of cold international relations at present, and seem pretty powerless. But when we say that these cultural exchanges belong to the "masses", it is precisely because they impact specific individuals or certain communities to varying degrees. It is difficult to say what these impacts would be - some people could have their hearts warmed or inspired, while others could change their lives because a seed was sown.

There is little coverage in the US about Echoes of Ancient Tang Poems, which was performed in commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the Philadelphia Orchestra's tour of China. I do not know if the Philadelphia Orchestra will visit China again in a few months. But I feel that the efforts of my Suzhou friends could be planting some new seeds.

Time, rather than the state of China-US relations, will tell whether their hard work will pay off. Who knows? Years from now, someone may recall that they had heard Tang poems sung to the accompaniment of the Philadelphia Orchestra in early 2023, and the way they had entered another cultural palace.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as "民间文化交流的力量".