Why democracy is failing and why some authoritarian regimes might just work

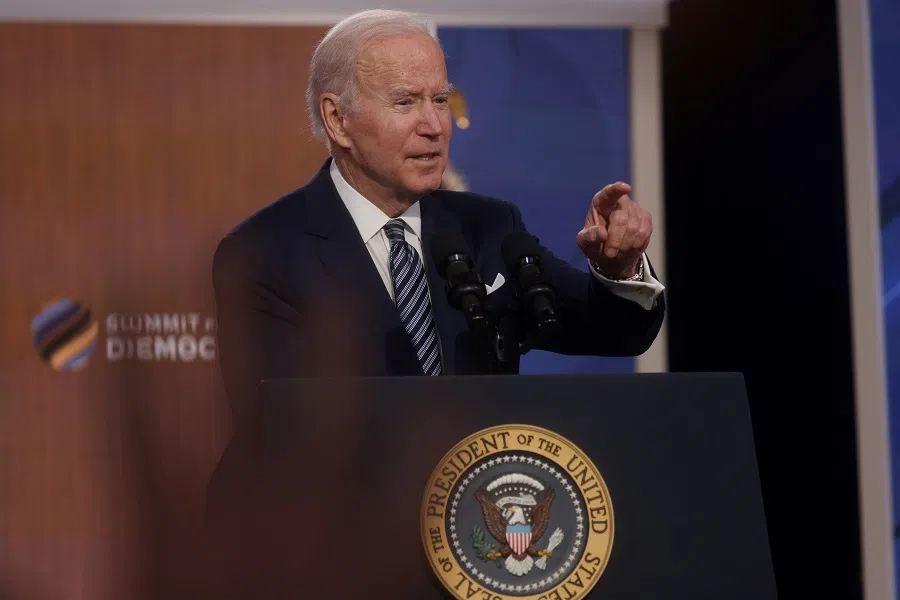

Lance Gore notes that US President Joe Biden's Summit for Democracy is one that will fade away just as quickly as it appeared. Fundamentally, the summit and the "good versus evil" dichotomy it espouses is way past its time. With democracies today, not least the US, facing issues of decline and some authoritarian regimes offering practical governance and livelihood solutions, the clash of systems is just not so clear-cut. In fact, if China irons out some of the kinks in its system, it may become a model of benign authoritarianism that others may find worth emulating.

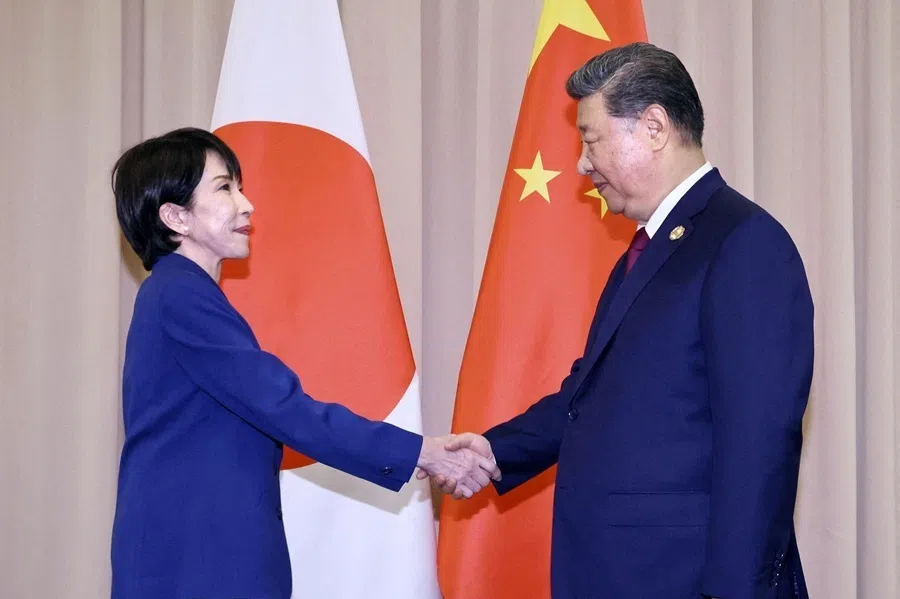

Recently, for the first time in history, top leaders or official representatives from as many as 110 countries and territories gathered for a virtual Summit for Democracy. Even so, just as the participants disappeared from the big screen at the end of the summit, the impact of this grand event will also vanish quickly, because the event put up a show of the same old song and dance which ignored the fact that the world is already quite a different place now.

Good vs evil outdated

Putting aside the summit's background of international politics for now, let us consider the matter on its own merits. The Summit for Democracy germinated from an ancient mode of thinking: that of the fateful struggle between good and evil.

The Cold War was supposedly a clash between democracy and freedom on one side, and the evil empire on the other. The forces of good won a resounding victory, the communist camp collapsed overnight, and with that, the third wave of democratisation began.

However, over the last two decades, democracy has been ebbing away all around the world, whereas authoritarianism and strongman politics are on the rise. The evil empire, as the narrative goes, has resurrected from the ashes, so it is time for the forces of good to fight back.

All this sounds like an invigorating morale booster, bursting at the seams with positive energy. But the sense of righteousness here masks a fundamental question: Why is there continuous turmoil in the democratic countries, whereas the forces of authoritarianism are in the ascendant everywhere?

The trend cannot be easily explained in terms of good versus evil. And yet the mythic narrative continues to be mainstream. Under the pressure to stay "politically correct", no one on the left dares to question it, while those on the right are instantly labelled as "evil" the moment they step out to call a spade a spade.

As a result, the politics in many Western countries lapses into prolonged, pointless altercation and spirals into a dead end. Meanwhile, a slew of livelihood-related problems are left untouched in the real world. The long-accumulated discontent of the general populace finally breaks out, spelling turbulence and crisis for democratic politics.

Fundamentally, it's all because there is a growing divergence between the concerns of the politicians and those of the common folk. The politicians have switched things out. The appeals of the masses are swallowed up in their existing system of discourse, melted into a morality play.

The president has never explained on what basis he is so sure that the old ways that failed can somehow "work" now. It's as if every problem can be solved by simply taking the moral high ground.

Joe Biden's high-sounding words at his summit say it all: "We stand at an inflection point in our history, in my view... Will we allow the backward slide of rights and democracy to continue unchecked? Or will we together - together - have a vision and the vision - not just "a" vision, "the" vision - and courage to once more lead the march of human progress and human freedom forward?"

Since the start of his presidency, Biden has proclaimed his desire to prove that "democracy works". Unfortunately, his policy agenda is almost entirely a repeat of the Democrats' hackneyed number. It strives to seize the moral high ground at every turn.

The president has never explained on what basis he is so sure that the old ways that failed can somehow "work" now. It's as if every problem can be solved by simply taking the moral high ground.

Biden is treading the worn-out path when America is hungry for change. No wonder he is seriously slipping in the polls. People just can't see him offering any way out. Running in circles will only leave liberal democracy behind the times.

Social cleavages in democratic societies

Putting aside the moralistic talk of essential "good" and "evil", let us analyse how democratic and authoritarian systems are actually doing - that is to say, how they perform in solving real-life problems. By doing so, perhaps we'll be able to clarify the true reason why one side is rising and the other is falling. First, let's look at democracy.

Even though "democracy" is currently held in high esteem, the original meaning of the term was connected to mob rule and oligarchic monopoly, the two extremes a democratic system is prone to slip towards. (With "political correctness" looming over them, very few dare to speak of a "mob" presently. "Populism" is as far as they can go.)

Both extremes exist in reality, and are the root cause of democratic politics going off-track, sapping democracy of its ability to solve real-life problems. For democracy to truly "work", it must resolve some fundamental issues.

It's no longer "one man, one vote", but "one dollar, one vote". That is a major reason behind the decline of democracy and the rise of populism.

The first of them is the influence of money. This is nothing new. In times of peace and prosperity, such influence is tolerated by the people. However, under the conditions of globalisation, the transnational flow of capital separates the interests of capital from those of its home country's working population. The rich-poor divide is widening all the time, so much so that the two sides have become two different worlds.

Election campaigns require substantial funding, which allows politicians to be hijacked by capital to varying extents, such that they overlook or misrepresent what the electorate wants. The voters gradually realise that the government they elected does not seem to represent them. It's no longer "one man, one vote", but "one dollar, one vote". That is a major reason behind the decline of democracy and the rise of populism.

Secondly, there are more and more livelihood-related issues that electoral democracy cannot resolve, including the big ones like income distribution, climate change, war and peace, terrorism, medical and social insurance, infrastructure building etc., as well as smaller ones like gun control, maternity leaves, poverty alleviation, and pharmaceutical monopolies.

Electoral democracy misapplies economic market theory, assuming that competition of the every-man-for-himself kind will naturally lead to the maximisation of social benefits, fairness and justice. What's really happening is that when people jostle for gains for themselves, their respective groups, classes, races, religions etc. legally and feel fully justified in doing so, the common good is neglected. The coordination and compromising function of politics fails.

The whole range of social problems on hand - everything from gun violence, mental illness, homelessness, broken families, low-quality school education, poverty, to public security problems in the low-income communities and organised crime - cannot be dealt with comprehensively at the root. Leveraging the procedures and loopholes of the system, interest groups can openly and legitimately profit themselves at the expense of the common good, with immunity from the law.

Thirdly, there is the issue of the marginalised demographics. These include the poor, the homeless, ethnic minorities, the mentally ill, native peoples, farmers, children, the disabled, the uneducated and so on. The politicians are never truly concerned about them, because they are difficult to mobilise, have no money for campaign contributions, and seldom vote. Very few political players truly speak for these people and represent their interests.

Fourthly, there is the issue of social cleavages. It first emerged in the Third World. Because of reasons of religion, race, language, culture, historical resentment or feud etc., many of these new nations lack a common national identity. To enforce Western-style democracy on them is to provide a legal means and moral basis for separatist forces. The result is often prolonged socioeconomic listlessness, political unrest, armed conflicts or even breaking up of the country.

This dynamic has presently come to haunt developed democracies. Even some long-established countries are at risk of falling apart: think Scotland of the UK, Quebec of Canada, and Catalonia of Spain.

Now, partisan struggles have come to the point where elections are won just for their own sakes and motions are voted down just for the sake of voting them down, all in disregard of national principles and the interest of the general public.

In the US, the split occurs along ideological fault lines. Democratic politics is no longer able to bridge the gap in the electorate, giving rise to vigorous discussions in several states about seceding from the American Union and becoming independent.

How democratic elections can be implemented in a divided nation remains an unanswered question and democratic politics itself encourages social cleavage is also a fact. The US presidential election of 2020 had exposed for all to see the flaws of procedural democracy, to which the state-controlled media and netizens in China responded with booing and the clinking of glasses.

Fifthly, there is the problem of effective governance and situational response. That the rhythm of elections makes politicians short-sighted and flip-flop on policies has long been widely criticised. Now, partisan struggles have come to the point where elections are won just for their own sakes and motions are voted down just for the sake of voting them down, all in disregard of national principles and the interest of the general public.

The government's credibility dips to new lows repeatedly. Partisan fight prevented a resolution for the US debt crisis, with repercussions on the global economy as well as on the world's fight against the Covid pandemic.

Greater institutionalisation and lesser freedoms

Lastly, liberal democracy is morphing into its antithesis in some countries. In order to safeguard human rights, civil liberty, equality and justice etc., governments have come up with a plethora of increasingly detailed rules and regulations, for which more and more bureaucratic agencies are created for oversight and enforcement.

State intervention into the lives of the common folk is getting more and more serious. The cumulative consequence is that people feel less free and democratic, for they are surrounded by a minefield of easily violable laws and taboos and feel increasingly helpless in the colossal shadow of the government.

Thanks to the liberalist creed of the supremacy of the self, identity politics has proliferated, political correctness spreads like a plague, and the rule of law degenerates into rule by lawyers. The quality of life deteriorates, social discontent increases, social conflicts escalate into social cleavage, destroying the consensual basis of electoral democracy, announcing electoral campaigns resembles declarations of war. As such, liberal democracy is likely to end up somewhere neither liberal nor democratic.

Biden has resolved none of the issues outlined above. He has not even faced up to them squarely. All he does is brandish the vacuous slogan "Democracy Works". No wonder democracy is on the decline. According to a research report by the Centre for the Future of Democracy at the University of Cambridge in 2020, global dissatisfaction with democracy has reached its highest level across the international community since 1995 when the survey began. Covering 154 countries, this report represents the most expansive survey to date on democracy.

Its results show that, over the last quarter of a century, the proportion of people in the developed countries who are discontented with "democratic politics" has grown from one-third to more than half. The corresponding proportion across the globe has climbed to 57.5%. According to a poll recently released by the Pew Research Centre, up to 57% of those polled thought that the American democratic system is not worth emulating. Only 17% saw "American democracy" in a positive light.

Could one of the reasons for the resurgence of authoritarian politics be that some authoritarian governments are performing better than Western-style democracies in tackling the problems mentioned above?

Authoritarian governments may do better on bread-and-butter issues

And now let's look at authoritarianism. In the liberalist conviction, all authoritarian governments are evil and must be opposed. But not all authoritarian regimes are the same. Just as there is malignant authoritarianism, there is also benign authoritarianism. Forms of authoritarianism are not all cast in the same mould.

A legitimate question to ask is this: Could one of the reasons for the resurgence of authoritarian politics be that some authoritarian governments are performing better than Western-style democracies in tackling the problems mentioned above?

Take two of the themes of the recent Summit for Democracy - corruption and human rights - for example. Singapore, which was not invited to the summit, has long been ranked as one of the least corrupt countries in the world. In mainland China, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)'s anti-corruption campaign, which is unprecedented in terms of scale, duration and intensity, has so far removed over 400 high-ranking officials of at least the provincial or ministerial level from power. This does not square with the traditional image of an authoritarian regime.

The post-war East Asian economic miracle was historically almost wholly achieved under authoritarian governments - the rule of one party or the dictatorship of one man.

Now let's turn to the issue of human rights. When the masses are demanding for the rights to survival, security, fairness, employment, housing, education, medical services and so on, the politicians are fighting for their right to vote and freedom of speech.

Careful analysis indicates that almost none of the desired rights listed above are covered under the abstract "human rights" advocated by the West. For young African Americans who live in ghettos, growing up in single-parent families, dropping out of school at a very early age, constantly unemployed, spending their days in the midst of narcotics, gangsters and gun violence, wasting away with an average life expectancy that is constantly falling, just what kind of human rights do they need more? For a homeless vagrant living exposed to the elements, what meaning do voting and speech have?

Just like democracies, authoritarian regimes come in all shapes and sizes.

On the other side of the world, mainland China is known not only for its economic growth, but also for one other miracle - its elimination of absolute poverty. Of the number of people successfully lifted out of poverty around the world since the beginning of this century, more than 70% are contributed by China.

The systematic, planned, sharply targeted and enormous efforts put in by the CCP for such an achievement are beyond what most democracies can do, given that a huge investment of manpower and material resources is required, and especially when there are no votes or any other returns to be gained.

Just like democracies, authoritarian regimes come in all shapes and sizes. Such regimes differ in their capacity to meet the needs of their people and in the extent to which they achieve that, but they all share one thing in common: they require the people to sacrifice some power and freedom in exchange for the meeting of those needs.

From the perspective of the common folk, human rights are more about practical issues than a question of metaphysical morality or principles. It follows then that the comeback of authoritarian regimes and strongman politics does not necessarily indicate something sinister or that villains are having their way. Instead, it reflects a great extent the demands of the masses. When the livelihood-related conditions have deteriorated far enough, even the American people may usher a great dictator into power.

If the democracies of today fail to overcome the flaws enumerated in the foregoing, they will hardly be able to compete with China in the long run. If China were able to get rid of some of its own old habits completely, level up on all fronts, become more humanised, and make substantial progress on its "whole-process democracy", it can become a benchmark for benign authoritarianism, or even an exemplar for the democratic countries to emulate.

Related: Will the Summit for Democracy unite or divide the world? | A low-confidence US, an unconvincing democracy summit | War of words: China and the US tussle for speaking rights on democracy | Beijing Olympics diplomatic boycott: Does China care? | Can there be a China-style democracy? | How the CPC plans to seize the democracy narrative