A Singaporean in China: Can there be justice for trafficked women sold as wives?

One weekday afternoon, my husband took a day off from work and we went out for a walk around the city centre of Beijing. We came across an entrance to one of the many hutongs or old alleys that Beijing is famous for and walked in to explore.

Once we entered the labyrinth of alleyways, the hustle and bustle of the main street faded away into the background. There was almost nobody else around as we roamed through the narrow winding streets. Only after we were deep in the maze of the hutong did I realise that this little exploration could be dangerous. We had felt safe enough to walk into a secluded street in Beijing alone.

Not long after, we started to explore other hutongs at night. Once again, we were alone and there were few others each time we entered a dimly lit and unfamiliar hutong. Yet we did not feel unsafe. In our year and a half here, living in Beijing has felt as safe as living in Singapore and I marvel at how much this country has developed and progressed. However, my sense of security was shaken by some recent events.

Exposé on abduction and bride trafficking

In the past month, as successful young athletes all over the world were celebrated at the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics, another group of people grabbed the attention of many Chinese: the victims of abduction and bride trafficking.

In late January, a Chinese vlogger posted a video of a woman in a small shed on Douyin (the Chinese version of TikTok). Chained by the neck, the woman was only wearing a thin layer of clothing in the cold weather and seemed to have some cognitive issues as she could not answer the vlogger's questions. It was later revealed that she was the mother of eight children in the Feng county of Xuzhou, Jiangsu province. After her circumstances were made known, she was brought to the hospital by the authorities and was diagnosed with mental illness.

When I first read the news, I thought it was a case of a mentally unwell woman who had too many children with her uneducated husband. However, as more people spoke up and more details came to light, I realised the sinister nature of the case.

These victims range from 14-year-old girls who were abducted on their way to school, to university students who were tricked and kidnapped when they travelled to remote areas for fieldwork.

In the beginning, local officials claimed that the woman was legitimately married to a local man. Netizens reacted with disbelief and were enraged. Under public pressure, an investigative team was sent to Xuzhou and the woman was later identified to be a missing person from Yunnan and a victim of bride trafficking.

Soon, more stories about females who were abducted and sold as brides to impoverished Chinese rural villages circulated online. These victims range from 14-year-old girls who were abducted on their way to school, to university students who were tricked and kidnapped when they travelled to remote areas for fieldwork.

I had heard about child abduction cases in China even before moving to Beijing, and we used to remind ourselves to hold our children's hands when we were on the streets. But after some time, we found Beijing a pretty safe city to live in.

In fact, local parents let their children run freely in parks and malls; some even leave them at indoor playgrounds while they take a nap on the massage chairs outside. They do not seem to be too concerned about the risk of abduction, and we also became more relaxed.

Hence, these stories of trafficking sent chills down my spine and reminded me of the famous crime prevention slogan in Singapore: "Low crime doesn't mean no crime."

Contributing factors

A traditional Chinese preference for boys over girls and China's one-child policy are some of the factors contributing to bride trafficking. The implementation of the one-child policy from 1980 to 2016 led to the illegal abortion and killing of female babies in many parts of China as those families hoped to have a son "to carry on the family lineage". The resultant gender imbalance is more pronounced in outlying regions as the local women leave their hometowns in search of better lives in the cities, while no women living outside these poverty-stricken villages would want to get married to men from these villages.

The villages are usually very secluded, and the practice of buying brides is so common that almost every family does it.

However, the single men in these villages still feel the societal pressure to marry and have children, particularly sons. They are so desperate that they resort to buying wives, spending their entire life savings. Sometimes, the whole family would chip in to pay. This creates the market for human trafficking.

Various reports also explained why it is almost impossible for abducted victims to escape. The villages are usually very secluded, and the practice of buying brides is so common that almost every family does it. If a victim tries to escape, fellow villagers will alert the family immediately and the girl will be caught in no time. Once captured, she will be brutally beaten up and locked away. Sometimes, the victims are drugged by the abductors on the way to the villages and could end up overdosed and cognitively impaired for life.

The Chinese movie Blind Mountain (《盲山》) released in 2007 follows the struggles of a girl tricked and sold into marriage in these remote areas of China. Her harrowing experience mirrors the story template of real-life victims who have been kidnapped, sold and abused. Watching it, I felt helpless thinking about the plight of women in these situations and the sense of hopelessness they must feel facing it all alone.

One such initiative wants leaders to raise the maximum punishment for human traffickers and buyers to the death penalty.

Saving the helpless

On 23 February, China announced that more than a dozen local officials in Jiangsu province have been fired, punished and investigated in the Xuzhou case. Officials also announced a crackdown on the trafficking of women, pledging to investigate cases that infringed on the rights of women, children and mentally disabled people.

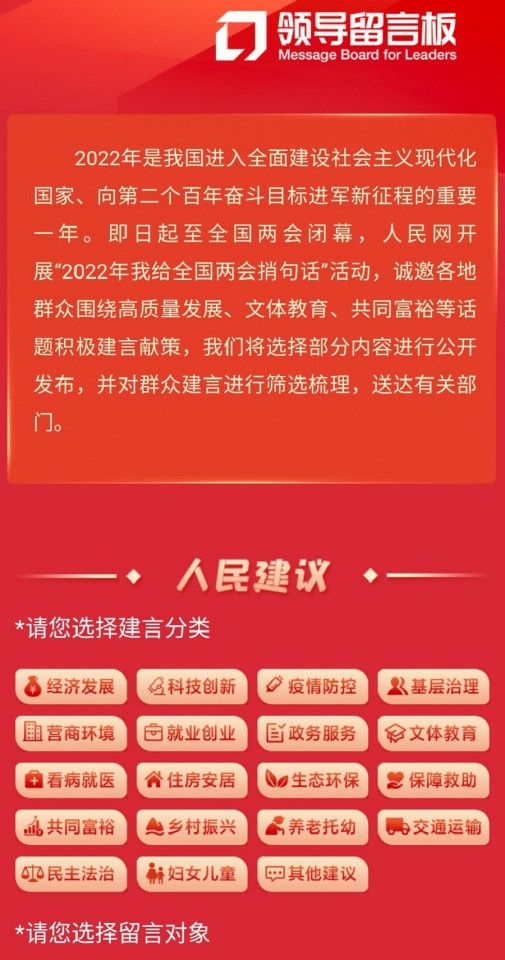

Still, the public is demanding more action from the authorities. There were calls for locals to write in to the "Message Board for Leaders" on the People's Daily Online website for the Two Sessions (两会, Lianghui) annual meetings in Beijing starting 4 March to share their concerns and wishes.

One such initiative wants leaders to raise the maximum punishment for human traffickers and buyers to the death penalty. It also advocates setting up the Amber Alert system in China, and the use of big data to search for missing women and children.

On 2 March, China's Ministry of Public Security announced the launch of a ten-month special operation to crack down on abduction and trafficking of women and children amid efforts to better protect these groups.

China has prided itself on the tremendous economic development it has made in the past few decades. Now, its people are demanding for more to be done for fellow citizens - whether these are women athletes with medals around their necks or women victims with literal and invisible chains around their bodies. It is only when a country takes care of the needy that its society can truly progress.

Related: Why extended maternity leave will not encourage childbirth in China | 'The world has abandoned me': Chinese women married into slavery? | Why China is the biggest winner of the 2022 Winter Olympics | How China's corrupt ex-police official Sun Lijun gained clout in the CCP | Elderly Chinese want a second chance at love | Chained mother of eight brings attention to abduction and sale of women in rural China | 'Leftover men' in the Chinese countryside and 'leftover women' in Chinese cities