Carving contemporary expressions: The Chinese art of seal carving

Recent exhibition Carving Possibilities, presented by Siaw Tao Chinese Seal Carving, Calligraphy and Painting Society, showed how artists across generations are reinventing the ancient Chinese art form of seal carving. Former journalist Teo Han Wue shares his observations.

(All photos courtesy of Teo Han Wue.)

If you think the ancient Chinese art of seal carving is too esoteric, made and appreciated only by a shrinking bunch of old fogeys entirely out of sync with the digital age, you need to get updated.

In Singapore in particular, one often laments young people's lack of interest in the Chinese language and culture. But you'd be surprised by how the tradition is alive and thriving, going by the popularity of a recent exhibition.

Carving Possibilities, presented by Siaw Tao Chinese Seal Carving, Calligraphy and Painting Society, ended its week-long run recently at de Suantio Gallery of the Singapore Management University. The exhibition attracted a good number of keen visitors, predominantly young people.

A diverse society of carvers

Besides the exhibition proper, there was also a fully booked workshop and an enthusiastically attended curator tour in English. The organisers published a highly informative and richly illustrated English/Chinese catalogue booklet, copies of which were given out free to all visitors.

On display were more than 320 pieces of work created by 32 members of the society aged between 24 and 71, all of which aptly reflect the theme of possibilities with a clear emphasis on how this form of artistic expression can be such great fun for the creator as well the viewer.

Indeed, while the exhibition's English title focused on "possibilities", its Chinese title 嘿,篆刻还可以这样玩 (hei zhuanke hai ke yi zhe yang wan, "Hey, seal carving can be played this way") stressed the fun and playfulness that can be derived from an art usually perceived as stuffy and outdated if not humourless.

It was the first time that the society had engaged an independent curator to put together a show featuring exclusively members' seal carving works, most of which were results of their monthly yaji (雅集, elegant gatherings), much like workshop sessions, conducted by their instructor Oh Chai Hoo, a well-known painter, calligrapher and ceramicist.

The brief given to curator Michelle Lim, 33, was to show how seal carving could be presented in various interesting ways making it more accessible in keeping with contemporary life in form and spirit. In her sensitive and thoughtful curatorial essay in the catalogue, she describes such possibilities as "the contemporary frontier of Chinese seal carving" and that the exhibition "seeks to survey the state of the craft in this day and age and posits its potentials for future exploration".

Michelle met Oh Chai Hoo when she was writing about his seal carving exhibition for online magazine Plural Art Mag in 2021. She became interested in his work and joined his classes and workshops on discovering that the art form was closely akin to printmaking, which she had learnt as an art student in New York.

...the material for carving a seal need not be restricted to stone, bronze and jade, as has been customary in the tradition...

New materials, new layers of meaning

Just what exactly made this latest series of Siaw Tao's seal carving work so special and worthy of note?

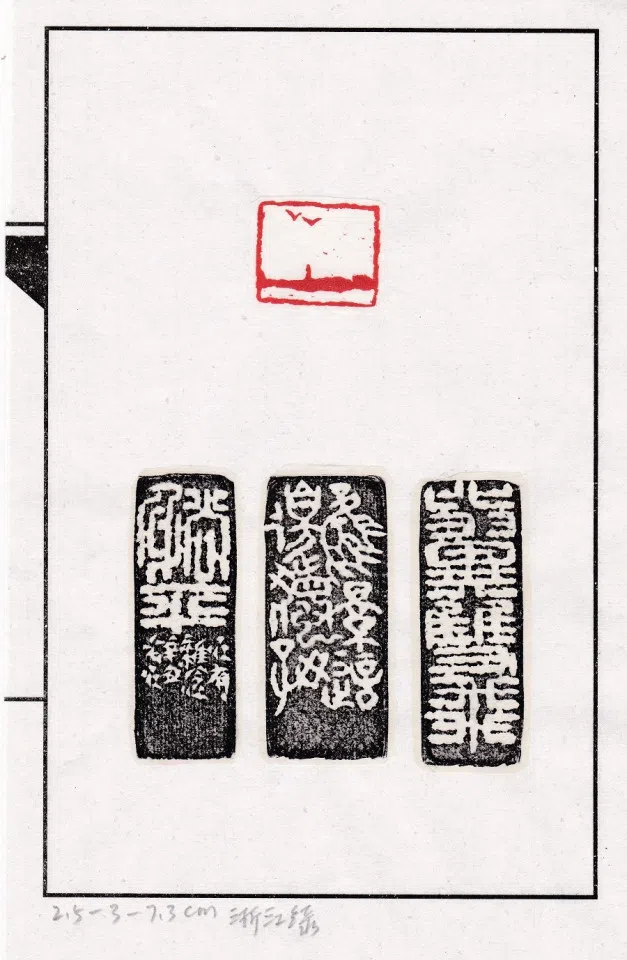

First of all, the material for carving a seal need not be restricted to stone, bronze and jade, as has been customary in the tradition associated more with aesthetic standards of refined taste and connoisseurship in Chinese antiquities. We see this being completely subverted with the use of a great variety of material besides different sorts of stone, such as ceramic, wood, cement, bricks and even chopsticks and mahjong tiles.

One can almost picture the artist holding up the block saying: "Look how enormous and heavy this seal that I have carved! I could crush you with it!

For instance, the cement block with a ring handle chosen by artist Soh Suan Cheok to carve on, lends considerable weight to the phrase ya si ni (压死你, "crushing you to death") with the character ya crushing or pressing down on the other two characters as though forcing them out of the frame, sounding almost like a tongue-in-cheek taunt. One can almost picture the artist holding up the block saying: "Look how enormous and heavy this seal that I have carved! I could crush you with it!"

Another of Soh's weighty pieces, po jiu li xin (破旧立新, "breaking down the old to build the new"), comes in the form of an actual brick carved with two characters jiu (旧, old) and xin (新, new). The juxtaposition of the two characters in the frame showing the character jiu in zhuanshu (篆书) seal script in its broken, disintegrated form, and xin in kaishu (楷书) regular script being propped up on a brick-like oblong shape, deepens the meaning of the text with the other two characters pictorially articulated instead. The imagery is further extended with the phrase fanghuo shaoshan (放火烧山, "setting the hill on fire") carved lengthwise on the side of the brick, presumably alluding to the need to burn down the trees in the hill in order to build something new.

Perhaps inevitably, this unusual seal must lead one to think of the saying pao zhuan yin yu (抛砖引玉, "casting a brick to obtain a piece of jade"). Isn't it apt for the artist to have chosen a rough-surfaced brick rather than an exquisitely delicate jade to carve on?

Besides, carving seals on the massive and rugged surfaces of such obviously oversized objects breaks away from the miniaturist tendencies in Chinese traditional aesthetics and defies the established convention of making a virtue of daintiness and intricacy entrenched in such a practice.

They introduce everyday spoken lingo, colloquialisms, simplified characters, and even Jawi, Javanese scripts and Singlish to boot.

Space for social commentary

Spurning the usual classical poetic phrases and passages being inscribed showing off literary flair and finesse, veteran painter Tan Chin Boon chooses to make hard-hitting social commentary instead with his cheeky satirical take on the current attitude of tang ping (躺平, "lying flat") among a growing number of young people in China, that is, copping out of intense competition in their working life.

It is a minimalist pictorial composition with a man lying flat showing a prominent erection looking towards the sky at a pair of birds in flight. One can guess how the young man in his position of giving up and not striving still fantasises or craves a prospect filled with longing and desire.

The phrase tang ping means rejecting gruelling competition for a low-desire life. In facing a keenly competitive society in China, many among the young are opting for complete withdrawal due chiefly to a sense of hopelessness or fear of not ever making it. One vertical side of the seal stone is carved with the phrase biyi shuangfei (比翼双飞, "flying side by side") alluding to happily-ever-after matrimonial bliss.

The real punch comes in the line fengjing zhebian du hao (风景这边独好, "the view is best over here") carved on another side. It is a line taken from Mao Zedong's poem written during the Long March expressing his optimism and determination in the outcome of the Revolution. Can anyone miss the irony as intended by the artist as criticism on this increasingly concerning social phenomenon in China?

Taking risks

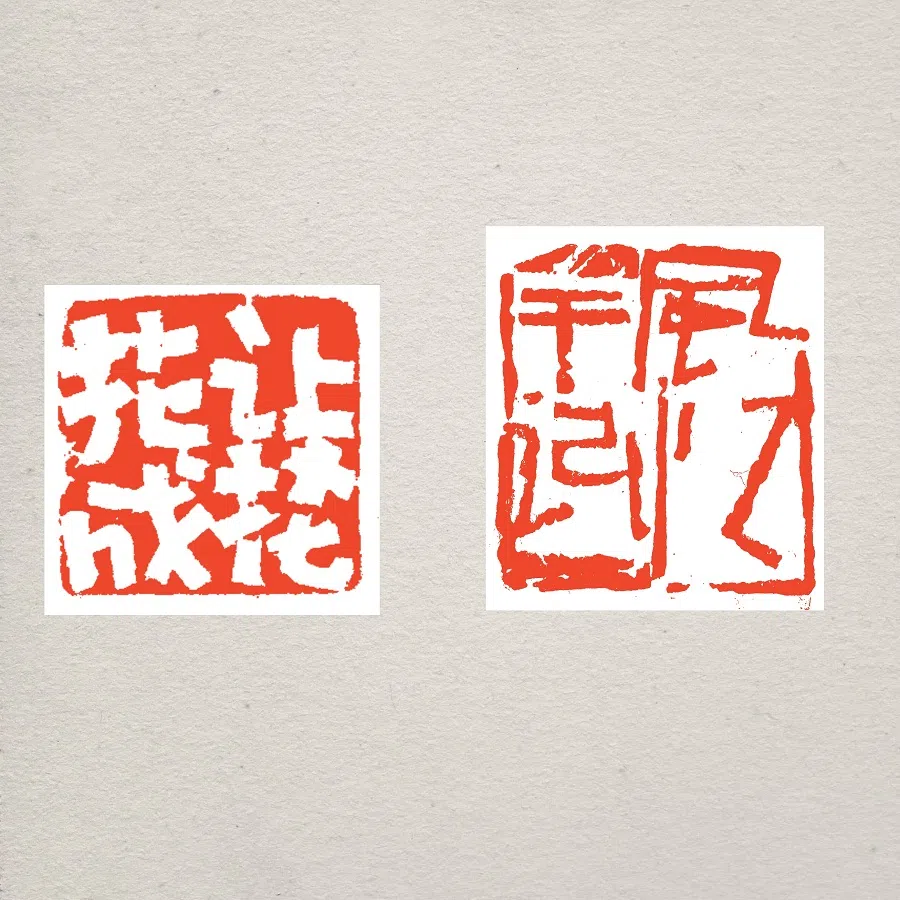

Moreover, a good number of carvers are venturing beyond the traditional rule of using the seal script zhuanshu and wenyan (文言, archaic classical Chinese) in what has for centuries been built on the foundation of written characters of the formal Chinese language. They introduce everyday spoken lingo, colloquialisms, simplified characters, and even Jawi, Javanese scripts and Singlish to boot.

Can we call such unusual artistic expressions... uniquely Singaporean, quite distinct from how it is practised in China and Taiwan?

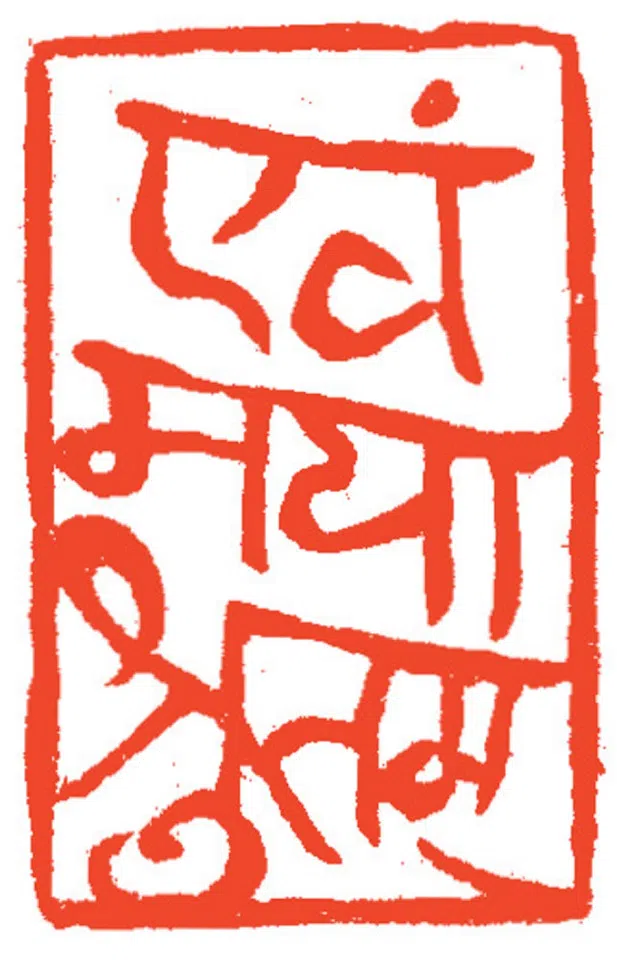

Oh Chai Hoo takes a risk with the sparse structure of simplified characters fenggan jiyi (风干记忆, "wind-dried memories") to create spatial tension in a rather challenging arrangement within the grid. Tay Bak Chiang tests the suitability of simplified regular script kaishu in his rang hua cheng hua (让花成花, "let flowers be flowers") and manages to make it work. Tan Yong Jun's "Merdeka" carved in Jawi script, "Nusantara" in Javanese script and "Evam Maya shrutam" in Nepalese script represent a boldest attempt in pushing the boundaries of the art form by carving non-Chinese characters on seal stones.

Though there were times in Chinese history when seals, especially those for official purposes, were carved in Mongolian and Manchu scripts, the mainstream has always remained the Chinese seal script.

For a moment an interesting thought crossed my mind on reflecting on what I had seen at the exhibition. Can we call such unusual artistic expressions, which its curator describes as the contemporary frontier of Chinese seal carving, uniquely Singaporean, quite distinct from how it is practised in China and Taiwan?

To my question, Siaw Tao instructor Oh Chai Hoo says: "Perhaps, I am not sure. But I have always advocated that members create seal carvings of our own and express our own thoughts and feelings as Singaporean artists notwithstanding what we have been taught to do with this ancient Chinese medium."