Colour and culture: Why did Confucius detest the colour purple?

Cultural historian Cheng Pei-kai takes a look at the perception of the colour purple in Chinese history. Was it always deemed as the colour of the imperial royals?

In the eyes of the Chinese, purple is a colour of royalty, imbued with an air of mystery and depth. It evokes the enigmatic allure of cosmic secrets, much like the northern lights, dazzling the mind and inspiring awe.

Merely a popular perception

It is a common saying that the emperor’s Hall of Supreme Harmony sits within the Zijincheng (Forbidden City, 紫禁城, where zi means purple), which corresponds to the Celestial Emperor’s Ziwei Palace (紫微宫), symbolising that the Son of Heaven ruled the world with Heaven’s mandate.

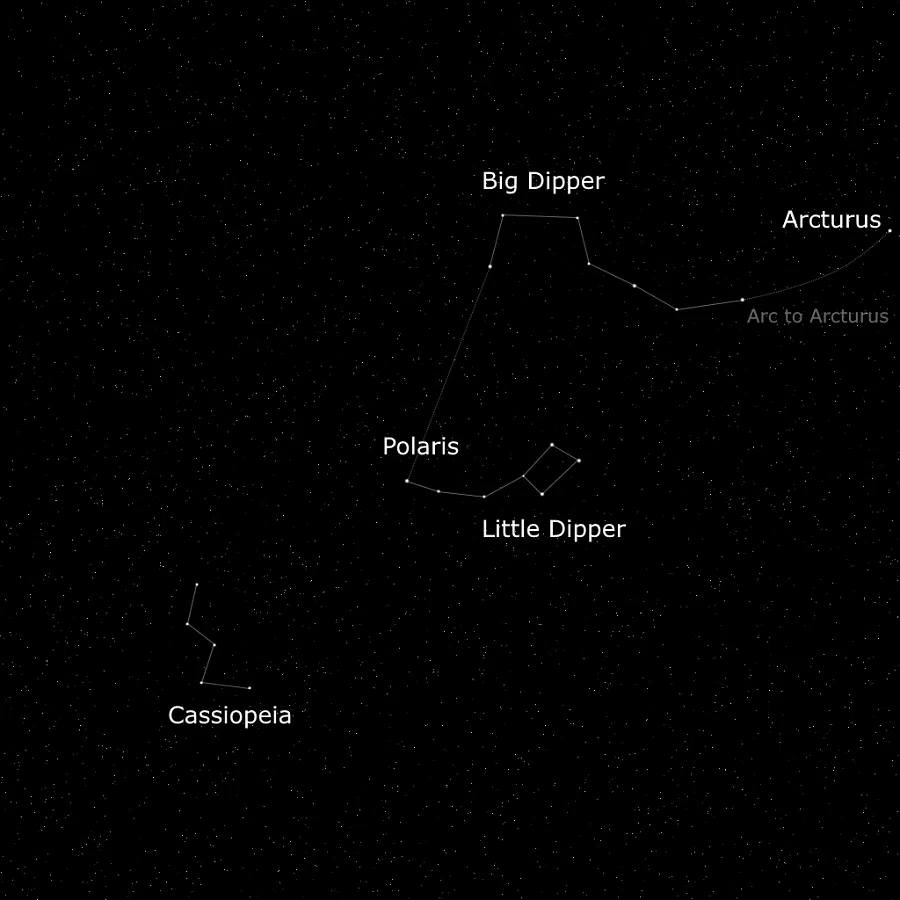

In ancient China, the concept of “unity of Heaven and humanity” (天人合一) shaped the design of the imperial city, aligning it with Ziweixing or Polaris (紫微星 or 北极星). This alignment emphasised that the emperor ruled with the highest legitimacy granted by Heaven, making his authority both sacred and inviolable.

In popular folk astrology, there is a saying: “The Ziwei Palace in Heaven and the Zijincheng on Earth”. Henceforth, ziwei (紫微), ziyuan (紫垣) and zigong (紫宫) became the byword for the emperor’s palace, while the colour purple became the most regal colour in popular perception.

However, we must keep in mind a few things, including the fact that the Forbidden City had not always been linked to the Ziwei Palace since ancient times.

... the association of purple with royalty and its use in the clothing of princes and nobles only became widespread after the Tang dynasty.

Firstly, the Forbidden City was built during the reign of the Yongle Emperor of the Ming dynasty. It has been passed down for 600 years from the Ming to Qing dynasties up until today, and has become a deeply ingrained historical concept for the ordinary Chinese.

Yet China’s history stretches far beyond 600 years. Given the widely recognized “5,000 years” of Chinese history, the concept linking the Forbidden City to the Ziwei Palace did not exist for several millennia before its development.

Secondly, ziwei doushu (紫微斗数, or purple star astrology), a form of fortune-telling, is not native to China. Instead, it came from India and Persia via the western regions during the Tang dynasty and only became popular in the Ming and Qing dynasties. In this sense, it is not a true-blue “national treasure” either. Moreover, the association of purple with royalty and its use in the clothing of princes and nobles only became widespread after the Tang dynasty.

Thus, the idea that Polaris is the “king” of the stars inziwei doushu or the “emperor star,” and that individuals with Polaris in their Self sector (命宫) possess the bearing of an emperor, lacks historical basis and is a product of the astrological culture of the Ming and Qing dynasties.

Confucius strongly disapproved of the popularity of purple, fearing that its alluring charm would replace the traditional and dignified red.

Disdain for the impure

So, has purple always been considered a noble colour since the advent of Chinese characters? Let’s examine what Confucius had to say on the matter.

In the Yang Huo (阳货) chapter of the Analects (《论语》), Confucius remarked: “I detest how purple diminishes the brilliance of vermilion. I detest how the songs of Zheng obscure the music of the Ya. I detest those who use their sharp tongues to overthrow kingdoms and families.”

This reflected two things: one, purple was beginning to surpass vermilion as a popular colour in the Spring and Autumn period. Two, Confucius strongly disapproved of the popularity of purple, fearing that its alluring charm would replace the traditional and dignified red.

Scholars from the Han and Jin dynasties have provided a fairly clear explanation of Confucius’ fear of how purple could diminish the brilliance of vermilion. In a commentary on the Analects (《论语集解》), He Yan quoted Western Han dynasty Confucian scholar Kong Anguo’s interpretation: “Vermilion, a standard colour (正色). Purple, a mixed colour (间色). Confucius hates that something evil (less pure) can overshadow what’s truly righteous.”

In another commentary on the Analects (《论语义疏》), Huang Kan noted, “Confucius disliked how purple diminishes the brilliance of vermilion because purple is a mixed colour, while vermilion is a pure, standard colour. He believed that standard colours should be preserved and mixed colours removed, reflecting his view that impurity should not influence the correct and righteous path. This metaphor was used to express his disdain for the way corrupt or immoral individuals were overshadowing the virtuous and upright in society.”

In yet another commentary on the Analects (《论语正义》), Qing dynasty scholar Liu Baonan pointed out that Mencius of the Warring States period knew very well what Confucius meant. He quoted Confucius in Meng Zi: Jin Xin II (《孟子尽心下》) which provided a thorough explanation, stressing that Confucius despised “a semblance that is not genuine”.

In a commentary of Mencius (《孟子注》), Zhao Qi further elaborated: “That which appears to be genuine but is not actually genuine is what Confucius detests.”

A Han dynasty encyclopaedia (《释名∙释采帛》) explained: “Purple, an improper/blemished colour. It is not a standard colour. It is a flaw among the five standard colours (五色) that deceives/misleads people.”

The relationship between vermilion and purple is one of primary and secondary. A primary-secondary relationship is tied to the order of Heaven and Earth, which must never be reversed.

Hierarchy in relations

Observably, the basis for Confucius’s disdain for how purple diminishes the brilliance of vermilion lies in the fact that vermilion is a primary, standard colour of paramount importance, while purple, being a mixed colour, is considered subordinate.

The relationship between vermilion and purple is one of primary and secondary. A primary-secondary relationship is tied to the order of Heaven and Earth, which must never be reversed. It is akin to the relationships between a ruler and his subjects, and a father and his child — relationships that are right and proper, and that cannot be overstepped.

Why is vermilion a standard colour while purple a mixed colour? This goes back to the ancient (but not only ancient) understanding of colour classification.

The colours in human cognition include the modern scientific primary colours of red, yellow and blue, as well as the five standard colours of red, yellow, blue-green (青), white and black in ancient times, which corresponded to the Five Elements (五行 wuxing: Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal and Water), and are considered primary attributes.

Purple is a “mixed” colour derived from mixing the standard colours, and is considered a secondary attribute. Thus, there is a clear distinction between primary and secondary.

Confucius’ stance not only reflects social ethics but also illustrates beliefs about the order of heaven and humanity, as well as the different properties of colours themselves.

Purple air from the East

Perhaps people will ask, “What does ziqi dong lai (紫气东来, lit. ‘purple air comes from the East’, implying the arrival of something auspicious) mean then?” Didn’t it come from Lao-Tzu?

This saying originated from Sima Zhen (679-732) of the Tang dynasty, who cited Liu Xiang’s Liexian Zhuan (《列仙传》, Biographies of Immortals) in his commentary on the Records of the Grand Historian (《史记索隐》): “When Lao-Tzu travelled westward, Yinxi, the legendary guardian of the pass, saw a purple aura floating over the pass, with Lao-Tzu riding a water buffalo through it.” This is also a legend that emerged later on, and had only become popular after the Tang dynasty.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)