Growing up with red packets: A Shanghai boy remembers [Eye on JiangZheHu series]

Red packets are not just cash; they are tiny bundles of nostalgia, family quirks and cultural pride. From the bustling chaos of childhood to the quiet satisfaction of giving, red packets have shaped his Chinese New Year memories in ways that money alone never could, says ThinkChina’s Lu Lingming.

With Chinese New Year just around the corner, the anticipation of celebrations brings back fond memories of red packets, a cherished tradition that symbolises blessings and good fortune.

Shanghai vs Singapore: A tale of red packets

During an office lunch, I discovered something surprising — red packets in Singaporean Chinese families often carry more symbolic significance than monetary value, with modest amounts meant to bring good fortune. Our casual chat took an unexpected turn when I mentioned that the tradition of red packets in Shanghai has always been generous, usually around 500 to 2,000 RMB (US$68-US$275). My Singaporean colleagues were visibly surprised. Clearly, red packet customs vary wildly, but that is what makes them fun.

Then there are the “native Shanghainese”, whose roots trace back to old Shanghai county. These families have lived in the region for generations, often since the late Qing dynasty or early Republican era.

Growing up, Chinese New Year for me meant going back with my dad to the countryside of Shanghai for a big reunion dinner, until our old rural “mud-brick” house was demolished. In Shanghai, people implicitly divide locals into two groups. The first group comprises broadly defined Shanghainese, whose ancestors migrated to the centre of Shanghai from Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces more than three generations ago, contributing to the city’s vibrant culture.

Then there are the “native Shanghainese”, whose roots trace back to old Shanghai county. These families have lived in the region for generations, often since the late Qing dynasty or early Republican era. They mostly live in the suburbs, and speak with a stronger, richer accent. My dad is one of these natives, while my mom grew up in the bustling city centre. Thanks to them, my Chinese New Year experience was like flipping between two TV channels with very different content.

I still remember using nicknames like 小嗯奶 (Small Grandma), 中嗯奶 (Middle Grandma), 大嗯奶 (Big Grandma), and 凶嗯奶 (Fierce Grandma) to tell them apart.

My father’s side adhered to more traditional customs. He had a sister, and my grandparents’ generation had even more siblings. I still remember using nicknames like 小嗯奶 (Small Grandma), 中嗯奶 (Middle Grandma), 大嗯奶 (Big Grandma), and 凶嗯奶 (Fierce Grandma) to tell them apart. “嗯奶” was our affectionate term for grandmother, and these nicknames added a bit of fun to the chaos, making the memory feel vivid and lively. The house always buzzed with chatter, laughter, and the occasional argument over mahjong rules. Meanwhile, my mom, an only child, kept it chill — just the three of us enjoying a cosy dinner. She only met up with one or two close relatives, leaving the rest to enjoy their peace and quiet. Polar opposites, right?

Distant relatives would politely give me red packets containing around 500 RMB. Close relatives, however, were more generous, gifting red packets with 1,000 to 2,000 RMB.

Love wrapped in tradition

Visiting my father’s place for Chinese New Year Eve meant immersing myself in a bustling crowd. Also, more relatives meant more red packets. There is no fixed amount for red packets, but generally, the less familiar the relative, the smaller the amount they tend to give. Distant relatives would politely give me red packets containing around 500 RMB. Close relatives, however, were more generous, gifting red packets with 1,000 to 2,000 RMB. Over on my mom’s side, things were quieter but richer. Her few close relatives often gave red packets with unexpectedly large amounts, sometimes matching the total I received from my father’s extended family — especially after I went abroad for my studies.

... as digital payment platforms like Alipay and WeChat became popular, the rules of receiving red packets also evolved.

Over time, I got so good at guessing red packet amounts that I could practically sniff out the cash inside, much like seasoned mahjong players who can identify tiles by touch. Most of my red packets were handed over to my parents, but even keeping a small portion was enough to make me feel triumphant among my peers. Back then, most kids my age had to hand over the whole stash, while I got to splurge on things like the latest sneakers or games.

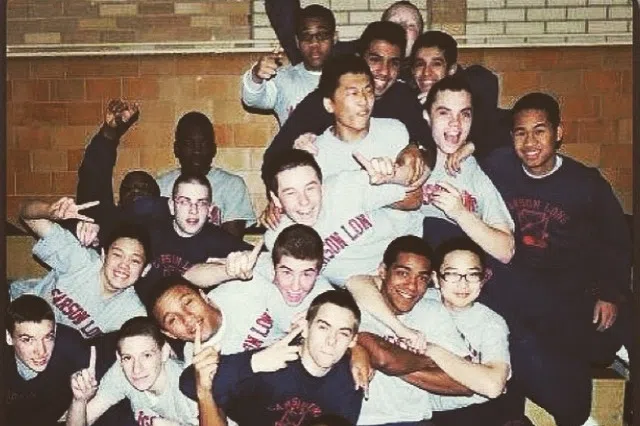

After moving to the US at the age of 14, Chinese New Year became a nostalgic occasion. Fortunately, as digital payment platforms like Alipay and WeChat became popular, the rules of receiving red packets also evolved. The physical red packets of my childhood were replaced by online transfers, allowing me to preserve my New Year’s money without the bittersweet feeling of surrendering it to my parents.

... the amount I received started to grow, as if more money could offer more protection. My grandma went from giving me 2,000 RMB to sending me 10,000 RMB, and continued this tradition until I graduated from college.

The name for red packets, “压岁(压祟)钱”, literally means “the money to suppress evil spirits”. Apparently, my relatives believed that living abroad in the US was quite dangerous — especially after seeing news about drugs and guns. As a result, the amount I received started to grow, as if more money could offer more protection. My grandma went from giving me 2,000 RMB to sending me 10,000 RMB, and continued this tradition until I graduated from college.

During high school, I attended a military academy, where almost every aspect of our lives was strictly regulated — including our allowance. Each week, we were only allowed to take US$20 from our teachers, which, even back then, was not much. Sure, inflation was not as crazy as it is now, but US$20 could barely cover two orders of sesame chicken or boneless ribs during our weekend takeout. Meanwhile, in just a few days of the Chinese New Year period, I would receive hongbao money that was over a hundred times my “weekly income”. For a teenager, this was not just exciting or joyful — it was on a whole different level. Looking back now, the only emotions that might come close would be if I won the jackpot or got my Singapore PR approved on the first try.

Even if I did not manage to spend it all during the year, I would reward myself with a “year-end bonus” right before the next Chinese New Year, clearing out my little stash.

With all that money, I would usually splurge on something big right away — maybe a pair of Jordans, trendy clothes from Supreme, or the latest gadgets like a PlayStation 3 or iPod. After that, I would divide the rest across my monthly expenses, trying to make life at the military academy a bit more comfortable. Saving? That was not even a thought back then. I was living the “moonlight clan” lifestyle way before adulthood. Even if I did not manage to spend it all during the year, I would reward myself with a “year-end bonus” right before the next Chinese New Year, clearing out my little stash.

Since they could not be with me often, red packets filled with money became their way of showing care — a tangible reminder that I was always on their minds, no matter the distance.

From receiving to giving: the journey of a red packet

In Shanghai, unmarried folks under 30 can keep collecting red packets. However, entering the workforce signals a shift in roles for me. Technically, by tradition, I am not at the stage where I need to take on these “adult” responsibilities yet. But knowing that I will not be getting married anytime soon, and having received so much love and generosity growing up, I figured — why not start embracing the feeling of being a grown-up now? Now, I find myself as the uncle working in Singapore, preparing red packets for nieces, nephews, and even friends’ kids.

As I was writing this article, I also spoke with many friends around my age. In terms of red packet amounts, it is true that in Shanghai, the money people typically receive starts at 500 RMB and goes up to around 2,000 RMB. However, having a relative who gives a 10,000 RMB red packet every year is definitely not common. And for a teenager to be allowed to keep all their red packet money? That is like the ultimate childhood fantasy kid dreams of growing up.

Red packets are more than cash; they carry love, hope and blessings.

Looking back, I realise that it was probably due to my unique family background and unusual upbringing that I seemed to receive more material love compared to other kids. On the emotional side, however, my relatives, including my parents, did not have many opportunities to connect with me in person, as I was studying at a military school perched in rural Pennsylvania in the US. Since they could not be with me often, red packets filled with money became their way of showing care — a tangible reminder that I was always on their minds, no matter the distance.

Transitioning from receiving red packets to giving them out feels like levelling up in life — a reminder of how traditions evolve with us. Red packets are more than cash; they carry love, hope and blessings. While the amounts may vary across cultures, the sentiment remains universal: a heartfelt connection that ties generations together.