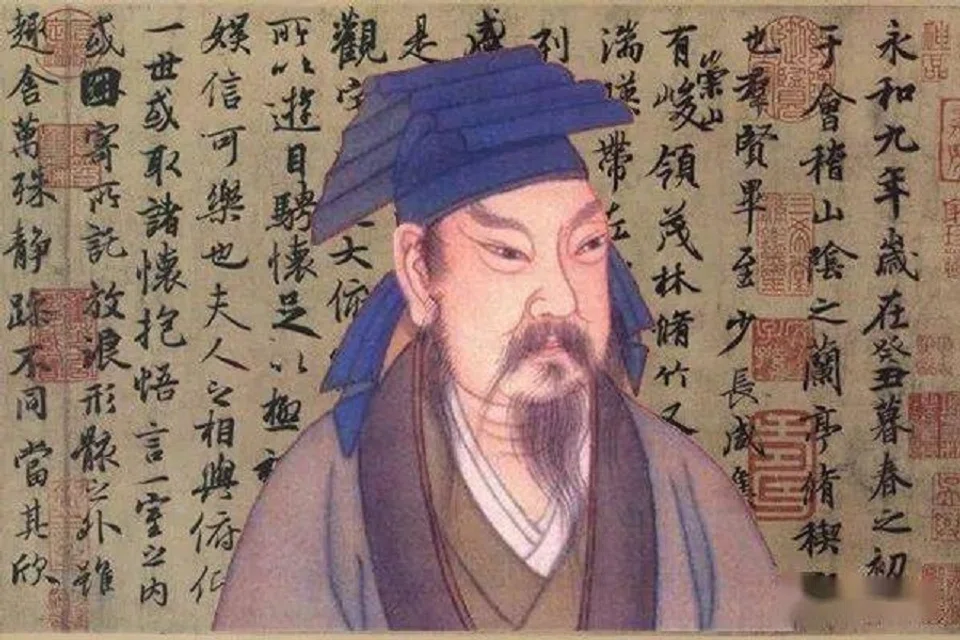

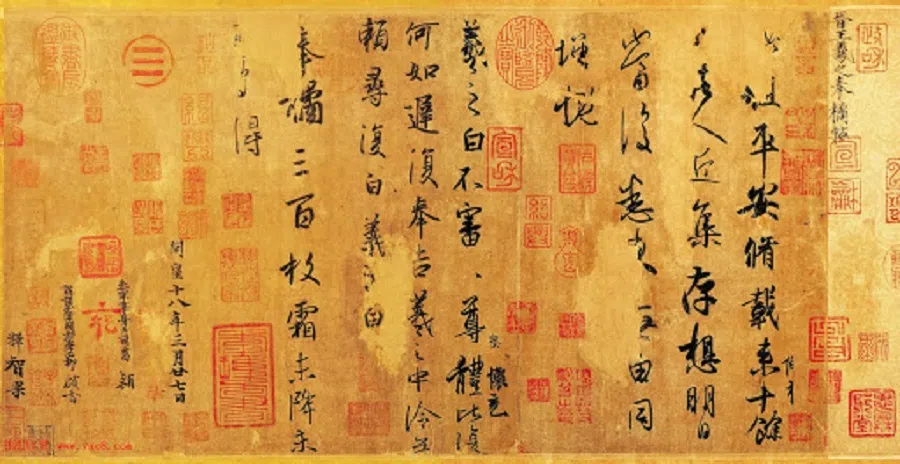

A pilgrimage of the heart: Paying homage to Jin dynasty calligrapher Wang Xizhi

Cultural historian Cheng Pei-kai takes us back to his trip to Shengzhou, Zhejiang, where he visited the gravesite of Jin dynasty calligrapher Wang Xizhi, the Sage of Calligraphy. In the depths of the lush forest with mountains peeking through, what does it mean to travel the distance to pay respects to an ancestor and honour their virtues?

Under the shroud of rain, the mountains looked like they were playing hide-and-seek. By the time we arrived at Jintingguan (金庭观), it was already three in the afternoon.

The sky was slightly overcast. Enveloped by a misty drizzle, the undulating mountains seemed wrapped in a veil of poignance, as if reminding visitors that this was the burial ground of the revered Sage of Calligraphy (书圣).

Unexpected detour

Jintingguan was excellently built. The gold characters on the plaque still had a bright shine, glowing like freshly lacquered paint. The front yard was tidy, the roof rafter stood tall and upright, and the beams and pillars evoked a sense of great solemnity, reminding one of the Yuewang Temple (Yue Fei Temple, 岳王廟) near West Lake.

However, there was no one in sight. There was just the pitter patter of rain, along with memories lost in time. I asked my friend who brought us here, "Why was such a magnificent temple built in the depths of the forest, and with no one around?"

Hearing that I was visiting Shengzhou to study the 800-year-old legend of Lady Qingfeng (清风娘娘), my friend, a Shengzhou local, urged me to stay for one more day to visit some of the more important cultural relics.

He said that Southern and Northern Dynasties poet Xie Lingyun had lived here and often fished along Shanxi (or Shan Creek 剡溪). The rock he sat on to fish was still there, and even the remnants of the base of the columns of his villa could still be found. The legacy of Chinese calligrapher Wang Xizhi (王羲之) was even more prominent.

After his retirement, Wang spent the remainder of his life in Shengzhou. His gravesite is situated at Waterfall Mountain (瀑布山) in Jinting town (金庭镇), a picturesque place that we had to visit. How could we not pay our respects to the Sage of Calligraphy? I happily tagged along.

Not only did my friend persuade me to make this detour, he also called along his nearly 90-year-old uncle as well as an expert from a local TV station that specialised in producing local culture programmes.

I later found out that my friend's uncle was an expert on countryside literature, especially local legends. He was a healthy old man with good hearing and vision, and was chatty but eloquent with a clear voice.

Unfortunately, he only spoke to us in the local vernacular, which I could understand only around 20%, so I had to rely on my friend to translate. Interestingly, the elderly man could vividly describe his childhood memories and local anecdotes before and after the war of resistance against Japan like it was yesterday.

Preserved for building relations

He was very knowledgeable about the reasons behind the rebuilding of Jintingguan and their consequences. Wang chose to live in Jintingguan after his retirement and was buried at Waterfall Mountain behind his residence when he passed away.

There is a small village behind his residence, where generations of gravekeepers resided for thousands of years until the modern period. They looked after the residence and the cemetery behind the mountain, and repaired and rebuilded the place.

Later on, as Japanese and Korean calligraphy associations made frequent pilgrimages to the site, the government realised the importance of Wang Xizhi in promoting friendly diplomatic relations with other countries.

During the campaign to destroy the Four Olds (四旧) during the Cultural Revolution, the Taoist temple was destroyed as it was seen as "feudal superstition". Later on, as Japanese and Korean calligraphy associations made frequent pilgrimages to the site, the government realised the importance of Wang Xizhi in promoting friendly diplomatic relations with other countries. Subsequently, they rebuilt Jintingguan, including setting up magnificent courtyards as a place to witness China's friendships with Japan and South Korea.

Now, there are regular annual festivals for the Japanese and Koreans to conduct extravagant and lively calligraphy events. Otherwise, the site is usually empty and quiet, with just a handful of Chinese visitors. I couldn't help but lament that even Wang Xizhi had to rely on the political needs of fostering friendly China-Japan and China-Korea relations to ensure a resting place - how embarrassing!

... it was all thanks to Wang's descendents that the stone tablet from the Ming dynasty was retained. They had secretly moved and buried it underground, only taking it out again after the end of the Cultural Revolution.

Mistaken pavilion

Treading the winding cobblestone path, we traversed a thick forest to reach Wang's grave. Standing before us was a stone pavilion with a single upturned eave and a stone tablet in the centre bearing the inscription "Grave of Wang Youjun of the Jin dynasty" (晋王右军墓; Youjun is Wang Xizhi's honorary title). The inscription was made in the Ming dynasty during the reign of the Hongzhi Emperor - nearly six centuries ago.

Behind the stone pavilion and tablet stood a ring-shaped stone mound covered by overgrown weeds. The elderly man said that the grave was built in the 1980s and only the stone tablet was a genuine relic - the rest were fake antiques.

Pointing at the right side of the front of the stone pavilion, he said that an ancient pavilion stood there, but it was destroyed during the Cultural Revolution - perhaps some unscrupulous locals were eyeing the stones used to build it and demolished it to build houses and erect walls, we will never know.

But it was all thanks to Wang's descendents that the stone tablet from the Ming dynasty was retained. They had secretly moved and buried it underground, only taking it out again after the end of the Cultural Revolution.

... it is possible that Wang's grave is not even at the current site but in the depths of Waterfall Mountain.

I said, "This stone pavilion also looks a little old. I guess it must be an ancient artefact too?" Upon hearing this, the elderly man excitedly gestured with his hands and loudly responded to my comment. I could only catch a few words about a chastity pavilion by the river and a widow's hat... I couldn't fully understand him.

My friend quickly translated, saying that this pavilion had nothing to do with Wang at all - it was originally a chastity pavilion erected by the river. It turned out that when Wang's grave was rebuilt, the stone tablet was intact but there was not enough government funding to hire workers to rebuild the pavilion.

Hence someone suggested removing the words on the chastity pavilion and moving it to the site of Wang's grave. But how could Wang Youjun's stone tablet be housed under a widow's pavilion as if wearing a widow's hat? What a big mistake!

Spiritual journey

As a local relics expert, the elderly man had voiced out at the time that doing so would be inappropriate, but his words fell on deaf ears and he was helpless as they made the blunder.

After he finished speaking, the old man suddenly pulled my hand towards himself and said with a laugh, "It is enough to fool the Japanese." His eyes lit up as he snickered - it was clear that he was mocking the deceivers and the Japanese pilgrims who were none the wiser.

However, it is possible that Wang's grave is not even at the current site but in the depths of Waterfall Mountain. The old man said that during the reign of Emperor Yang Guang of the Sui dynasty, Wang's grave had been destroyed and became difficult to locate. It was rebuilt several times in the later generations and was finally settled behind Jintingguan to make it easier for Wang's descendants to pay their respects and honour the virtues of their ancestor. Thus, the source of the building materials didn't really matter in that sense.

... the significance of a pilgrimage is in fact a pilgrimage of the heart, an act of externalising one's inner sincerity and reverence onto a spiritual journey to be made.

After hearing his perceptive explanation, I too felt that the significance of a pilgrimage is in fact a pilgrimage of the heart, an act of externalising one's inner sincerity and reverence onto a spiritual journey to be made.

The lush mountains and seas, as well as the grave overgrown with grass and weeds, are all external scenes for the cleansing of our heart of adoration and respect. The Wang Xizhi in everybody's heart, however, is a reputable name that will be fondly remembered forevermore.

This article was first published in Chinese on United Daily News as "參拜王羲之" in 2010.

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)