Taiwanese art historian: What do Su Shi, Mao Zedong and Jesus have in common?

Defamed by villains, ostracised by the imperial court and repeatedly demoted to barren lands — was Song dynasty poet and essayist Su Shi’s dire fate truly dictated by the stars of Capricorn? Taiwanese art historian Chiang Hsun muses on the rumblings and trivialities in Su Shi’s life.

In recent years, online discussions have buzzed with the revelation that Su Shi, the renowned Song dynasty poet and essayist, was a Capricorn. This has led some to question whether people from the Song dynasty, a thousand years ago, were even aware of horoscopes.

Our place among the stars

In fact, discussions about horoscopes date back not only to the Song dynasty but also to the Tang dynasty. Tang dynasty essayist and Confucian scholar Han Yu is an example. However, he mistakenly believed he was a Capricorn when he was actually a Sagittarian.

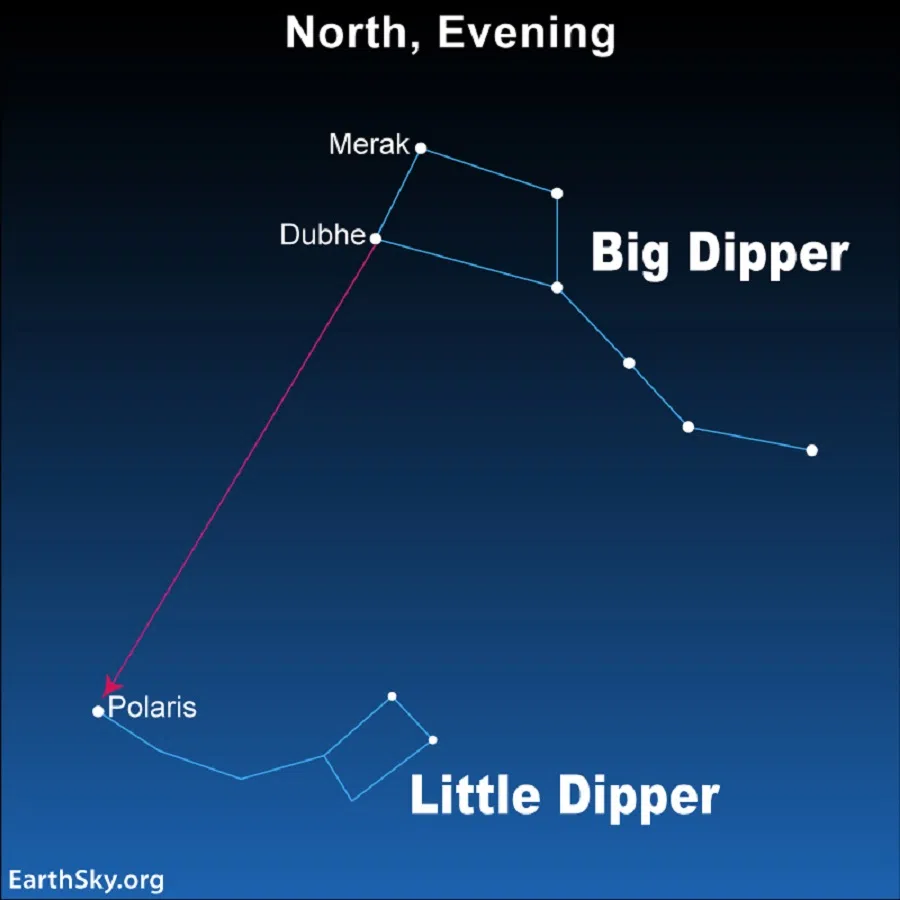

In his poem “San Xing Xing” (三星行), Han Yu discusses his horoscope and astrolabe: “I was born when the Moon was in the Southern Dipper. The Ox brandished its horns, and the Winnowing Basket opened its mouth.” This describes the astrological positioning of the stars at his birth. The “(Southern) Dipper,” “Ox,” and “Winnowing Basket” are part of the 28 Mansions in the ancient Chinese constellation system.

The seven stars of the Big Dipper and the six stars of the Southern Dipper are each arranged like a dipping spoon or ladle. The Southern Dipper’s stars also form part of the Western constellation Sagittarius. The Winnowing Basket, representing the tail of the Azure Dragon of the East, is shaped like a winnowing basket for sifting rice and corresponds to Sagittarius in Western constellations.

The Ox refers to Altair (the Cowherd Star), well-known through literary stories. It is the second mansion of the Black Tortoise of the North and sits beside the Southern Dipper. The Ox belongs to the Western constellation Capricorn, which led Han to believe he was a Capricorn. In reality, he had a Sagittarius Sun and a Capricorn Moon.

In a vast, indifferent cosmos, we search for our small, vulnerable selves.

Indeed, Han’s observations of constellations were very accurate. Yet, the real subject of “San Xing Xing” was not the constellations, but rather a scholar’s lament about his unlucky fate.

In the later lines of “San Xing Xing”, when Han Yu says that “the Ox is not pulling a cart, and the Dipper does not pour out wine”, he’s expressing his grievances. His lament about “treacherous individuals who do no good yet gain a good reputation, while upright individuals who have done no wrong are falsely accused” reflects his own misfortunes — being defamed by adversaries, ostracised by the imperial court, and repeatedly demoted.

He lifted his head and saw the three constellations in his astrolabe, 15 stars arranged from east to west. He pointed at the stars in the sky and lambasted: “The three stars in the heavens, arranged from east to west. Alas, you Ox and Dipper, where is your divine power?” What kind of stars are you, so powerless?

Today, reading horoscopes for fun has become quite popular, with media outlets eagerly joining the trend. Daily horoscope forecasts are ubiquitous, capturing global attention and often overshadowing news about political conflicts.

These horoscope messages are perhaps similar to Han’s case, where the primary focus is not on the constellations themselves, but rather on the desire to uncover one’s predetermined fate. Some people keep their eyes glued to horoscope websites every day, wanting to know how their love life or financial situation will turn out, or whether they will be scolded by their boss. Will they fall sick? What colour should they wear? What is their lucky lottery number?

In a vast, indifferent cosmos, we search for our small, vulnerable selves.

Like Han, we know our own astrolabe and horoscopes. But alas, the Ox does not act like an ox, nor does the Dipper act like a dipper. Only the Winnowing Basket opens its mouth wide, inviting a lifetime of gossip and trouble.

Are we truly reading the stars?

The 28 Mansions of the East spread to India and became 27. Babylon and Egypt observed the stars early on, which evolved into the rich Greek constellation stories. Western constellations have also spread to the East, illustrating the vibrant and fascinating history of cultural exchanges between East and West in the study of astronomical phenomena and constellations.

In the constellations, do we see the vastness of the universe, or do we only see ourselves?

Temper of an ox

I quite enjoy Han’s laments. He reminds me of many of my Sagittarian friends — bubbly, casual, and unafraid to speak their minds. They’re often so direct that they don’t realise they’ve upset a Virgo, who might turn pale in response.

With three Sagittarians in my astrolabe, I’m surrounded by many Sagittarian friends. Our meals together are often a boisterous — and at times overwhelming — affair. But then I am reminded that I have a Capricorn Sun and the three Sagittarians are already quite tame.

When the Sagittarians get unbearably loud, I would calmly remind them: Never touch politics.

“Why?” Sagittarians often think they know politics like the back of their hand.

History is replete with examples of meticulously planned coups, which their perpetrators believed to be flawlessly concealed, only to be swiftly and fatally crushed by their political enemies.

Han’s “San Xing Xing” mentioned the “Winnowing Basket”, which represents wind — the start of gossip and disputes.

Han was definitely aware of his big mouth. The emperor was a devout Buddhist and wanted to bring Buddhist relics from far and wide to the palace. Han wrote a lengthy and impassioned memorial to the emperor in protest. Ill-intentioned people who already disliked Han seized the opportunity, thinking, “How dare he oppose the emperor? He’s digging his own grave!”

They made a mountain out of a molehill, turning a minor issue into a life-or-death situation. Han was thus exiled to Chaozhou; perhaps gazing at the stars over there would knock some sense into him?

While in Chaozhou, Han wrote “Ji Eyu Wen” (祭鳄鱼文, A Sacrificial Message to the Crocodiles), reflecting his compassionate philosophy of “saving the world from drowning”. Although the crocodiles weren’t entirely eradicated, the essay remains a testament to an intellectual’s compassion for all living creatures.

Two centuries later, Su Shi, who admired Han, cemented Han’s unshakeable position in cultural history.

Su described Han with two key phrases that are widely known: “Han Yu’s essays reversed the literary decline of eight dynasties; his advocacy of Confucianism saved the world from drowning.”

The “literary decline of eight dynasties” is linked to Han’s “Memorial on the Bone of the Buddha” (谏佛骨表), where he criticised the ruler’s excessive reverence for foreign (“barbaric”) practices, advocating instead for the preservation of “Confucian orthodoxy”.

Not singing the same tune as the ruler, the Ox embodies a rebellious spirit. Perhaps Capricorns are destined to have the temper of an ox.

Han was not against Buddhism itself. He enjoyed a close friendship with eminent Buddhist monk Dadian. It is easy to misinterpret Han’s “Memorial on the Bone of the Buddha” as being against Buddhism, ideologically narrow-minded and xenophobic.

Perhaps we have overlooked that Han was specifically addressing Emperor Xianzong of Tang’s enshrinement of the Buddha’s finger bone relic brought from India. It is possible that the religion of the masses and that of the ruler should not be equated. Han might have believed that the ruler’s reception of the relic set a precedent and was a political statement, compelling him to speak out as a defender of Confucian orthodoxy.

What destinies do the three stars of Ox, Dipper and Winnowing Basket really govern in the heavens?

In a room full of subservient officials flattering the ruler, why did Han present such sharp criticism?

“Han Yu’s essays reversed the literary decline of eight dynasties” — literature wasn’t the only thing in decline. I suppose Su was highlighting an intellectual’s courage to salvage and revitalise the declining Confucian orthodoxy.

Not singing the same tune as the ruler, the Ox embodies a rebellious spirit. Perhaps Capricorns are destined to have the temper of an ox.

Luck of the Capricorn

Su must have been deeply moved by Han’s “San Xing Xing”, compelling him to also talk about his own horoscope.

Dongpo Zhilin (《东坡志林》) is a delightful book — not solemn, heavy or dogmatic. These short essays were Su’s casual notes, offering both entertainment and food for thought.

Looking at the Ming Fen chapter of Dongpo Zhilin, Su indeed began with Han’s “San Xing Xing”: “As Tuizhi (Han Yu’s courtesy name) writes, ‘I was born when the Moon was in the Southern Dipper.’ This tells us that Tuizhi’s ‘body palace’ is in Moxie (磨蝎). My ‘life palace’ is in Moxie, so in life I will face countless criticism and praise. I guess we have similar fates.”

Most of the online discussion about Su’s horoscope stems from this passage in Dongpo Zhilin.

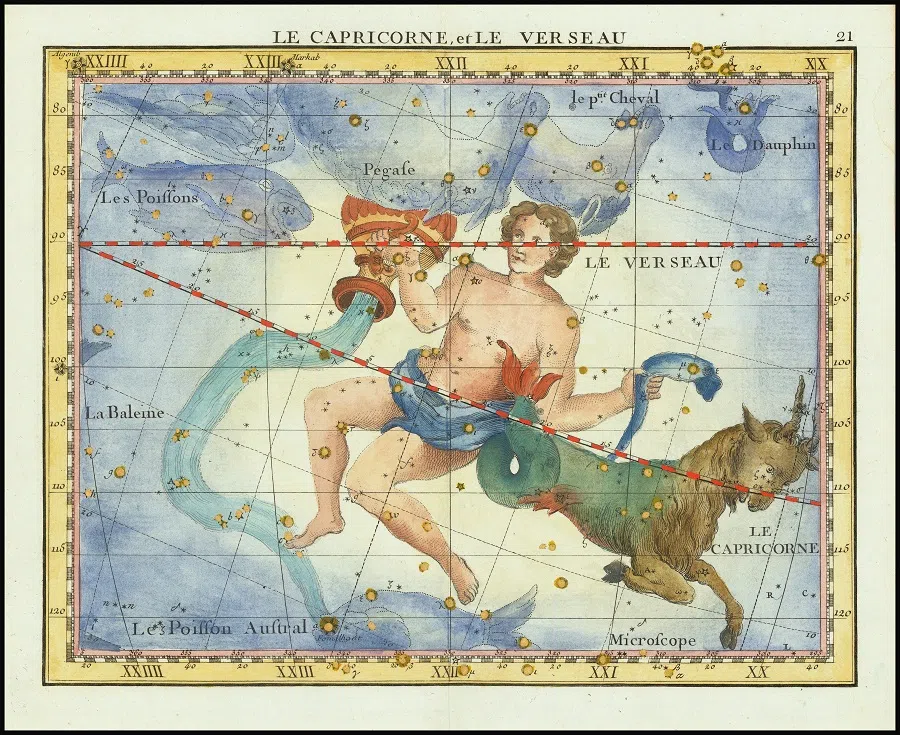

Moxie, or Mojie (摩羯), refers to the Capricorn horoscope. Tang dynasty Chinese Buddhist monk and scholar Xuanzang studied in India and became very familiar with Hindu mythology. In his book Records of the Western Regions (《大唐西域记》), Xuanzang mentions a sea beast called Moxie (磨蝎, pronounced Mohe), which has the body of a fish, the head of an elephant and crocodile teeth. Moxie is the transliteration of the Sanskrit word Makara.

The interaction and fusion of mythology and visual arts often transcends racial conflict, war and political division, forming a harmonious dialogue of cultures.

In both ancient Egypt and Babylon, the Capricorn constellation was depicted with the head of a goat and the tail of a fish. Later in Greek mythology, the Capricorn constellation retained its goat-head and fish-tail, and was given a myth: Pan, the Greek god of shepherds, with goat horns and the body of a goat, loves to sleep, chasing beautiful maidens upon awakening. When he was caught in a storm and fell into the water, his lower body transformed into a fish, while his upper body remained that of a goat.

The Capricorn image is ancient and widespread. With the Greek conquest of India, this “goat-head, fish-tail” image merged with the Moxie of Hindu mythology. They both feature the body of a fish, but their heads are not exactly the same.

The interaction and fusion of mythology and visual arts often transcends racial conflict, war and political division, forming a harmonious dialogue of cultures.

The “Moxie palace” in the ziwei doushu (紫微斗数, purple star astrology) of the Tang and Song dynasties has genetic links to ancient India, ancient Greece and even Babylon and Egypt. This image also has widespread influence among the masses, and can be seen everywhere, from ceramics and roof ridge decorations to jade and wood carvings.

Angkor Wat is heavily influenced by Hinduism and primitive Buddhism. I saw many Moxie images on the stone sculptures, and even found several restaurants named “Makara” online. The influence of mythology is indeed long-lasting and widespread.

In Dongpo Zhilin, Su noted that his life palace and Han’s body palace are in Moxie, so it is destined that they would face countless “criticism and praise”. They would be entangled in gossip and disputes, with petty people adding insult to injury, and were destined for a difficult life.

The terms “life palace” and “body palace” are used in Eastern astrology and fortune-telling. The former refers to an individual’s innate destiny, while the latter refers to the reality shaped by external circumstances. Some also believe that your “life palace” determines the first half of your life, while the “body palace” dictates the second half.

This is somewhat similar to the Sun, Moon and Rising signs in modern astrology. Su may have thought that since his “life palace” was in Moxie, instead of his “body palace” like Han, he would be subjected to even more sabotage from villains than Han.

This does still sound a bit like a literati’s grumbling. Of all things to compare, he is comparing who has more enemies and who has worse luck.

Han was demoted and exiled to Chaozhou, a land plagued by miasma, and almost couldn’t survive. He eventually put aside his ego and wrote to the emperor begging for mercy. Emperor Xianzong did not pursue the matter further and transferred Han further north.

Su didn’t know Jesus or Mao Zedong — both Capricorns.

Su was clearly more unfortunate in this aspect, and was exiled to Hainan in the end.

Are Moxies really this unlucky?

To be a Capricorn like Jesus or Mao Zedong?

Su not only lamented his own fate but also brought in a fellow Capricorn friend as further proof. The next passage in Dongpo Zhilin reads: “Ma Mengde was born in the same month and year as me, him eight days after me. Among those born during this period, none are wealthy. We would be on top if we were to compare who’s the poorest of them all. But between the two of us, Mengde should come in first.”

I believe Su’s calculations were not accurate at the time. If we had artificial intelligence (AI) and big data filtering, we could accurately compare how unlucky the Moxies had been.

Taiwan businessman Wang Yung-ching was a Capricorn. Although he was born into a poor family, he ultimately built a massive business empire.

Su didn’t know Jesus or Mao Zedong — both Capricorns.

Capricorns are hard-working and resilient, capable of success, and sufficiently rebellious. And the outcome of their rebellious nature was that one was crucified by the ruler, while the other became an even greater ruler.

It is difficult to say if Su had hoped to be Jesus or Mao Zedong?

Mao’s prose was bold and unrestrained, much like Su’s style. His “Qinyuanchun: Snow” (沁园春·雪), written in his youth, was exhilarating: “It’s a pity that Qin Shi Huang and Han Wudi were slightly lacking in literary talent; Emperor Taizong of Tang and Emperor Taizu of Song were somewhat inferior in cultural achievements. Genghis Khan, a hero of his time, only knew how to draw the bow and shoot the eagle. All these figures are gone now. As for those who can truly achieve great things, we must look at the people of today.”

Among modern and contemporary poems, only this one exudes the grandeur of founding a nation.

If he did not establish a nation, he could have been arrested and crucified like Jesus.

What type of Capricorn did Su want to become?

Grumblings and trivialities of a Capricorn

Su was born on 19 December in the Jingyou era (1036) of Emperor Renzong of Song. This is according to the Chinese lunar calendar, which converts to 8 January 1037 in the Gregorian calendar. He really was a Capricorn.

The Gregorian calendar did not exist then. How did Su convert the dates? How could he have not mistaken himself as a Sagittarian based on his birth date of 19 December?

I was born on 28 November of the lunar calendar in the 36th year of the Republic of China. A meddlesome friend converted it to the Gregorian calendar — 8 January 1948.

“You were born on the same day as Su Shi,” my friend mused, as if it was a big discovery.

Su had a pretty good life. Although he was framed by scoundrels and imprisoned, every place he was demoted to felt like a free trip.

Su complained that he was always surrounded by nasty people because he was a Capricorn. Actually, he could have easily found out that among the “villains” who framed him and wanted him dead during the Wutai Poetry Case (乌台诗案), some might have been Capricorns themselves.

Thus, there are Capricorns who live good lives and some who lead terrible ones. There are honest and upright Capricorns, and also others who are petty and nasty. It is better to be tolerant when observing constellations — in the age of AI and big data, one can scan hundreds of millions of Capricorns in a second and still not find one that is purely good or purely evil. The good and bad fortunes of life are woven from a tapestry of causes and effects; observe its workings quietly, and you will know that silence is golden.

I only discovered that I’m a Capricorn very late in life and am not affected by Su’s grumblings. Mother followed the lunar calendar and cooked me a bowl of plain noodles with a hard-boiled egg on the 28th day of the 11th lunar month every year, a small ritual wishing me peace and safety.

She would toss off a blessing in our hometown dialect: “Forget the eighth and eighteenth. The twenty-eighth is the real lucky day (福疙瘩).” There’s no logic to it, but it rhymes and rolls off the tongue, and you almost start to believe it. I love how this folksy saying turns the abstract fu (福, fortune, good luck) into something tangible, like a little gnocchi (疙瘩) or knot of blessings.

I hold dear the very simple and rustic bowl of birthday noodles and the catchy little song Mother made me.

Su had a pretty good life. Although he was framed by scoundrels and imprisoned, every place he was demoted to felt like a free trip. West Lake in Hangzhou goes without saying. Even in Lingnan, he delighted in the abundance of lychees, writing: “If I can eat 300 lychees every day, I do not mind becoming a Lingnan native.”

I think he was someone who could not hide his joy. Exiled to Lingnan, supposedly a punishment, everyone else would be crying their eyes out, but this Moxie was happily gobbling down lychees. Eating them was one thing, but he had to go so far as to write a poem about it. Angered, the ruler punished him further, banishing him to Hainan.

He should blame his big mouth and not the innocent Moxie.

In his later years in Hainan, a sort of languidness descended upon Su. I am particularly fond of his contemplation of the fading splendour of late spring: “After wine, I yearn only for slumber. The honey is ripe, yet the bees are too lazy to fly.”

After drinking, with his body ailing, and living in a foreign land, he truly wanted to sleep — a good, long sleep.

There is an anecdote in Dongpo Zhilin, a significant realisation of a Capricorn in his later years. I will share it here for those who are interested: “Two cuoda (措大, used to describe penniless and not-so-bright scholars in the olden times) were discussing their aspirations. One said, ‘I’ve never had enough all my life. I only desire sleep and food. If I make it one day, I wish to eat till I’m stuffed and then sleep, then wake up to eat some more.’ The other said, ‘I’m different from you. I only want to eat and eat. Who has time for sleep?’”

Few people use the term cuoda nowadays. When I was little, I often hear the elders call impoverished scholars “qiong cuoda (穷措大)”. Su might have heard a conversation between two poor scholars, where one of them shared his hopes that success will allow him the freedom to eat and sleep to his heart’s desire. The other, probably with a growling stomach, instead only hopes to satisfy his appetite.

Listening to, remembering and even writing about such a boring conversation between two poor strangers — that’s a Capricorn for you. This is what makes Su so lovable. It is even more characteristic of a Capricorn than all of his grumblings.

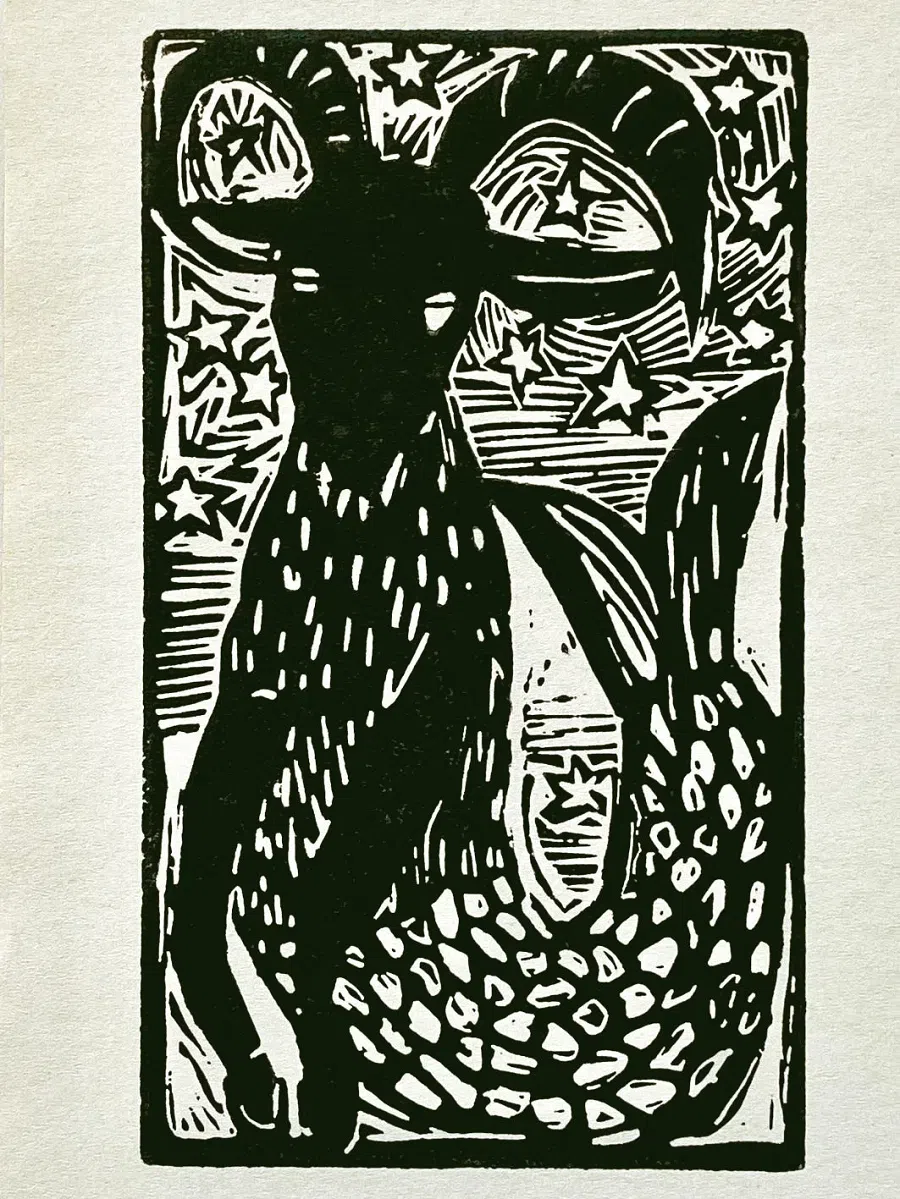

I would like to thank Xavier Wei for creating the woodcuts to accompany the text. He was from the third graduating cohort of the Department of Fine Arts at Tunghai University, and is also a Capricorn. He made two versions of “Capricorn” for me to choose from. I found both wonderful and worth sharing with the readers since space allows.

This article was first published in Chinese on United Daily News as “摩羯蘇軾”.