Web novels, web dramas and video games: China’s holy trinity of cultural exports reaches Singapore

Once confined to niche online platforms, China’s web novels, web dramas and video games are now taking the world by storm. In Singapore, local youths are embracing these cultural exports, which are rekindling an interest in Chinese culture. Lianhe Zaobao journalist Zhu Yuxuan explores their appeal to Singaporean audiences.

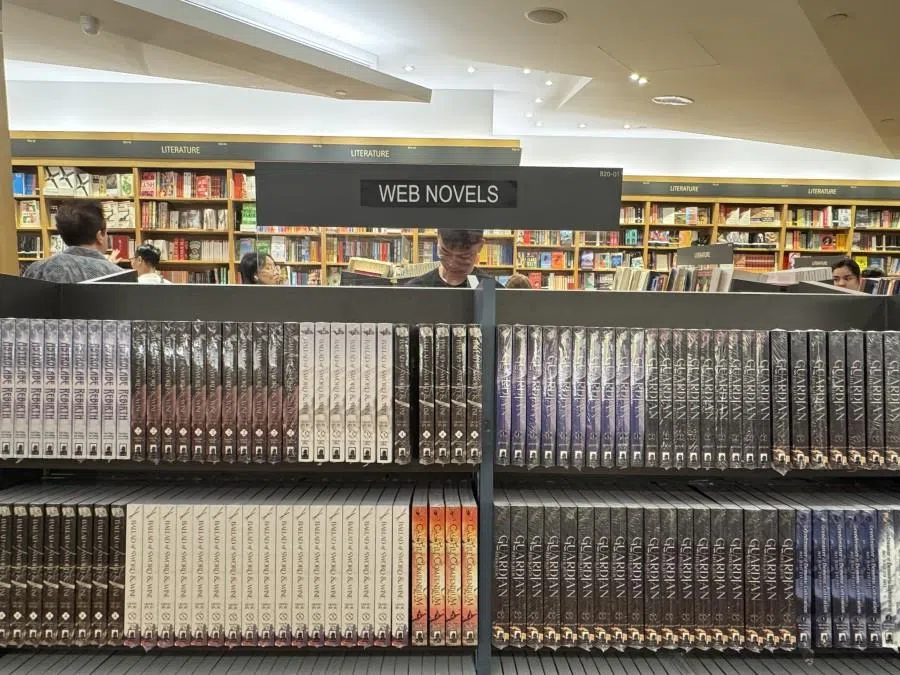

“I started reading web novels over ten years ago. Back then, I had to hop between all sorts of unofficial Chinese websites to find resources. I never imagined that nowadays they’d be everywhere — even Kinokuniya in Singapore carries English editions,” marvelled 28-year-old Qi Yue.

To her, this change is surprising but also reflects the growing global influence of Chinese culture in recent years. Today, China’s “new trio” of cultural exports — online literature, online games and web dramas — is rapidly going global, opening up markets worldwide and also becoming part of everyday life for Singaporeans.

Among them, online literature — spanning genres such as romance, mystery, fantasy and wuxia (martial arts fiction) — has seen especially remarkable growth. According to an industry report released by the Game Publishing Committee of the China Audio-Video and Digital Publishing Association, the overseas market for Chinese online literature exceeded 5 billion RMB (US$701 million) last year, with an overseas readership of more than 350 million.

According to the data, works that first emerged and flourished on platforms such as qidian.com (起点), fanqienovel.com (番茄小说) and Jinjiang Literature City (晋江文学城) are now increasingly catching the attention of overseas publishers, who are translating them into English and bringing them to a wider global audience.

University student Wang Haiying, 25, also “went down the rabbit hole” during her secondary school years. She not only reads the original Chinese versions, but also collects the English translations. “I’m very curious about how certain chapters are translated, so I often compare them.”

Chinese web novels make their way onto Kinokuniya’s bookshelves

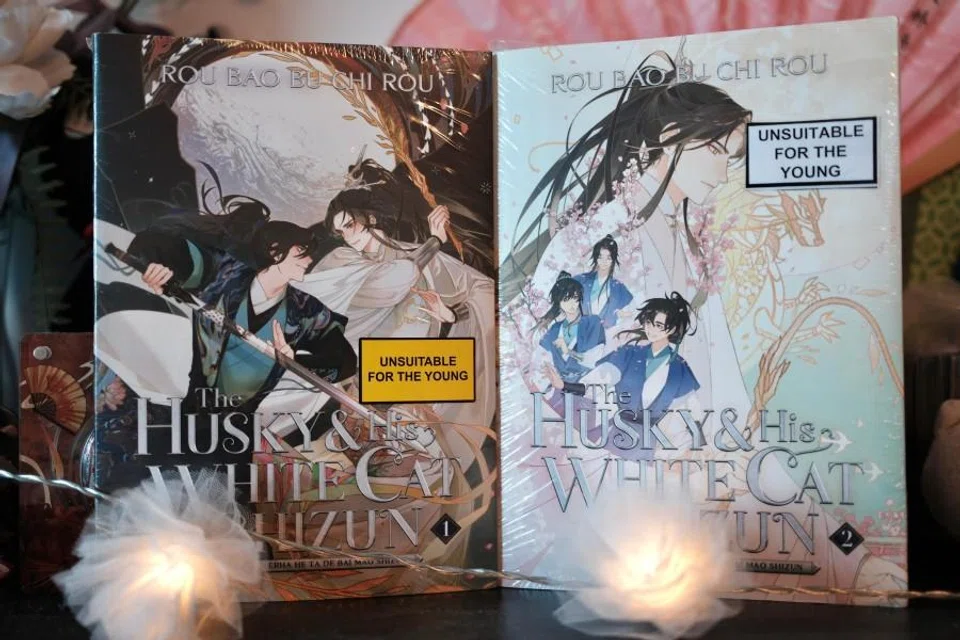

At Kinokuniya’s Orchard Road flagship in Singapore, the “Web Novels” section is now filled with English translations of Chinese online novels, including Thousand Autumns (《千秋》), Grandmaster of Demonic Cultivation (《魔道祖师》) and The Husky and His White Cat Shizun (《二哈和他的白猫师尊》).

Although these books are marketed as adult-only, many people first encountered them as teenagers. Qi Yue, who has just entered the education field, recalled discovering online fiction platforms at the age of 15. The novels there perfectly suited her taste, both in content and writing style, and she “fell in love with them ever since”.

University student Wang Haiying, 25, also “went down the rabbit hole” during her secondary school years. She not only reads the original Chinese versions, but also collects the English translations. “I’m very curious about how certain chapters are translated, so I often compare them.”

This has also made her aware of the limits of translation. For example, the martial arts technique “春水指法” in Thousand Autumns sounds elegant and poetic in Chinese, but when rendered literally into English as “spring waters finger technique”, much of its cultural resonance and lyrical beauty is lost.

In recent years, numerous Chinese web dramas — including Joy of Life (《庆余年》), Reset (《开端》) and Love Between Fairy and Devil (《苍兰诀》) — have gained international traction, thanks to strong word-of-mouth and fan followings.

Even so, Wang Haiying believes this does not diminish the reading experience for English readers. “The plot remains captivating. If readers truly like the story, they’ll naturally be motivated to explore the culture behind it.”

Seventeen-year-old Shreya, an Indian student browsing the English web novel section, said her interest in Chinese novels began when a classmate introduced them to her, and that she has bought one book from the store. “If the English versions weren’t available, I probably wouldn’t have discovered so many wuxia-related stories.”

The rise of Chinese web dramas

As the popularity of web novels continues to grow, web dramas have followed suit. Many are adapted from best-selling novels, and their success often fuels renewed interest in the original works.

In recent years, numerous Chinese web dramas — including Joy of Life (《庆余年》), Reset (《开端》) and Love Between Fairy and Devil (《苍兰诀》) — have gained international traction, thanks to strong word-of-mouth and fan followings. In Singapore, streaming platform meWatch has also added several hit series, allowing local viewers to easily keep up.

Frequent web drama viewer Qi Yue said that these stories allow her to temporarily escape from reality while enriching her inner world.

While their production budgets are often smaller than those of prime-time TV dramas aired on China’s major satellite channels, web dramas have still managed to capture huge audiences. Joy of Life is a prime example — its first season, released in 2019, became an instant hit. Meanwhile, the second season in 2024 broke records, becoming the most-watched mainland Chinese drama ever on Disney’s streaming platform.

Frequent web drama viewer Qi Yue said that these stories allow her to temporarily escape from reality while enriching her inner world. She was especially moved by a scene in Joy of Life where the protagonist recites the Tang poem “Bring in the Wine” (将进酒) — it sparked her interest in classical Chinese poetry.

Another avid viewer, Xie Wenyi, 27, a visual designer, prefers light-hearted series like The Romance of Tiger and Rose (《传闻中的陈芊芊》). She says it does not bother her that some people dismiss such shows as “mindless feel-good dramas”. “I watch dramas to relax — as long as they make me happy, that’s enough.”

At the same time, with the rise of short-video platforms, micro-dramas — bite-sized episodes lasting just one or two minutes each — are also gaining popularity overseas. 29-year-old project manager Chen Anqi, who often watches them after work, likes that they are fast-paced and satisfy her craving for stories while allowing her to unwind. “Also, the male lead acts well and is my type.”

The global surge of Chinese games

As the final pillar of China’s “new trio” of cultural exports, the country’s gaming industry is also making powerful strides overseas. In the first half of this year, revenue from Chinese-developed games abroad grew by more than 11% year-on-year, returning to the high growth levels last seen in 2021.

When talking about Chinese games, it’s hard not to mention the blockbuster Black Myth: Wukong developed by Game Science. Hailed as China’s first AAA-level title — referring to a game developed with major financial investment, resources, and time — it was released in August last year and shattered records within days. In less than five days, it broke Steam’s concurrent player record and surpassed 28 million copies sold worldwide, topping the 2024 global sales charts.

As a fan of the novel Journey to the West, Li appreciates how the game [Black Myth: Wukong] preserves classic elements while reimagining them through a new protagonist — the “Destined One” — in a refreshing take that deconstructs and reconstructs the moral worldview and narrative framework of the original work.

The Wukong fever has spread to Singapore as well. Accountant Li Jiawen, 28, said he was captivated the moment he saw the game’s trailer back in 2020. He bought Black Myth: Wukong as soon as it was released and has since logged nearly 110 hours of gameplay. For him, the appeal lies not only in the gameplay mechanics but, more importantly, in the cultural symbolism behind it.

As a fan of the novel Journey to the West, Li appreciates how the game preserves classic elements while reimagining them through a new protagonist — the “Destined One” — in a refreshing take that deconstructs and reconstructs the moral worldview and narrative framework of the original work.

He believes that such reinterpretations are not only creative but also help rekindle players’ interest in Chinese culture. Some of his friends, after playing the game, have gone back to reread Wu Cheng’en’s Journey to the West, and revisited its classic film and TV adaptations.

As for Game Science’s upcoming title Black Myth: Zhong Kui, Li Jiawen confidently predicts that he will “definitely play it” and looks forward to seeing how the studio will offer a new interpretation of the legendary exorcist.

He also expressed strong interest in other Chinese-developed games, such as Lost Soul Aside (《失落之魂》). “There are plenty of games in this genre,” he said, “but they’re still incredibly appealing — I’d love to give them a try.”

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “从小说网剧到爆款游戏:中国文化新三样出海新加坡”.

![[Big read] Paying for pleasure: Chinese women indulge in handsome male hosts](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/c2cf352c4d2ed7e9531e3525a2bd965a52dc4e85ccc026bc16515baab02389ab)

![[Big read] How UOB’s Wee Ee Cheong masters the long game](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/1da0b19a41e4358790304b9f3e83f9596de84096a490ca05b36f58134ae9e8f1)