China’s soft power paradox: Censorship vs cultural exports

The export of Chinese pop fiction, including Boys’ Love (BL) fiction, has found ready markets in Southeast Asia such as Thailand. But some undesirable genres pose a dilemma for China’s soft power.

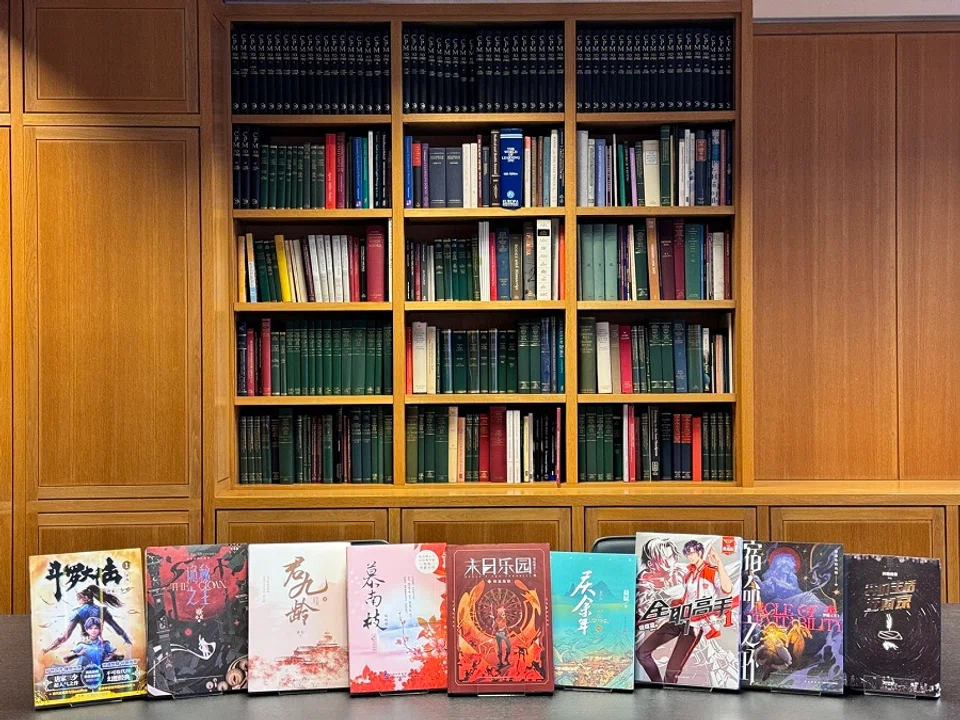

In recent years, Chinese pop fiction has gained significant popularity among young readers in Thailand and across Southeast Asia. While classical works such as The Romance of the Three Kingdoms have long been staples of the region’s literary landscape, the contemporary wave of translated Chinese pop fiction marks a distinct shift.

These works not only dominate Thai bookstores but also represent a departure from traditional narratives, offering fresh perspectives and resonating with young audiences in ways that classical literature may not. But this does not always resonate with the Chinese government as certain subgenres conflict with the soft power that China wants to wield in other countries.

Rising popularity

Popular Chinese pop fiction genres among Southeast Asian readers include time travel, xianxia (immortal heroes) fantasy drama and historical romance. The adaptation of Chinese novels into TV series, available on platforms like WeTV and IQIYI, has played a crucial role in this phenomenon.

Series such as The Untamed (2019) have attracted large audiences and heightened interest in the original novels they are based on. This synergy between screen adaptations and literary consumption has encouraged fan engagement across multiple platforms, increasing the visibility of both Chinese novels and actors, and fuelling interest in Chinese media content.

... many Chinese writers are now exporting censored content to Southeast Asian markets, where such themes are more widely accepted.

In contrast, Thailand’s domestic drama industry is struggling to replicate the same success due to economic difficulties and the rise of online platforms offering more viewing options. Moreover, Thai dramas, often limited to genres centred on marital relationships, fail to capture modern social realities or reflect contemporary society. This contrasts sharply with the varied genres and broad appeal of Chinese TV adaptations.

The export of Chinese literature introduces several positive elements to overseas markets. It fosters cultural exchange, enabling readers to learn more about Chinese cultural elements and core values. Moreover, some Chinese companies have managed to circumvent Chinese Communist Party (CCP) censorship by producing content that aligns with international standards while still adhering to domestic regulations. This strategy is evident in the global rise of C-Pop, where companies seek to escape strict censorship by appealing to broader markets.

However, not all genres enjoy the same level of freedom. The Chinese government has been stringent regarding online literature — especially Boys’ Love (BL) fiction — due to its potential conflict with state-approved values and standards. As a result, many Chinese writers are now exporting censored content to Southeast Asian markets, where such themes are more widely accepted. This strategy allows them to capitalise on the demand for BL narratives while navigating the constraints imposed by their government.

... exporting BL fiction is not beneficial to China because it contradicts the values that the CCP seeks to promote.

BL fiction rising

Chinese BL fiction, also known as Yaoi or Y, has gained remarkable success in the Thai literary market. This comes as little surprise, given Thailand’s recognition as a global leader in BL content. The growing appeal of Chinese BL fiction in Thailand and the rising popularity of Thai BL series in China presents an opportunity for future collaboration between Thai and Chinese production companies that could lead to co-productions or joint marketing initiatives. This broadens the audience for both markets.

But the Chinese government’s censorship and curtailment of undesirable content like BL fiction pose significant challenges for its soft power strategy. Soft power can be defined as the projection and export of values and standards that an exporting power believes will help it influence other countries in the cultural, ideological, and institutional spheres. From this perspective, exporting BL fiction is not beneficial to China because it contradicts the values that the CCP seeks to promote.

Room to manoeuvre?

While it is true that such censorship limits the export of materials from China to Thailand and other Southeast Asian countries, it appears that the CCP has calculated the costs and decided to proceed. In other words, the party seeks to project its cultural influence globally, yet seeks to balance its domestic ideological positions.

The government likely deems that exporting censored content — while potentially harmful to its image — serves a greater purpose by allowing for some cultural exchange without fully endorsing genres that conflict with its ideological stance domestically. This dual approach appears to indicate a clear polarisation in Chinese policy, where one set of regulations caters to the domestic market while another is designed for overseas audiences.

While China’s online literature thrives in Thailand and other parts of Southeast Asia, its potential for soft power influence is undermined by rigid censorship practices. The ongoing popularity of genres such as BL fiction highlights a complex interplay between demand for Chinese cultural exports and governmental control, raising important questions about the future of China’s cultural exports.

This article was first published in Fulcrum, ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute’s blogsite.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)