What else besides Nanyang art?

While Nanyang art is known as Singapore’s first local art movement, it is not the only genre of art that took root in Singapore in the pre-independence period. Happening alongside, says CEO of the Singapore Chinese Cultural Centre Low Sze Wee, was the rise of social realist art, and more.

Nanyang art is generally regarded as Singapore’s first local art movement. Starting from the 1930s, it reached a peak in the 1950s and 1960s before declining in the 1970s, especially after Singapore’s independence from Malaysia in 1965.

Its main practitioners were Chinese migrant artists who had settled in Nanyang during the first half of the 20th century. “Nanyang” meaning “south seas”, was a term traditionally used by the Chinese to refer to the maritime trading region south of China, which included places like Singapore.

Rise of Nanyang art

These artists shared similar backgrounds. Born in the early 20th century, they were schooled in China’s first modern art academies. They were among the first generation who were taught and became proficient in Chinese and Western art.

At the time, China’s imperial system had just been overturned. Many artists considered how Chinese ink painting should be modernised so as to better reflect China’s new status as a modern republic. Recognising China’s imperative for reform, some artists sought to synthesise the best of Western and Chinese art by relating Western art to their understanding of Chinese art.

... in the relatively more peaceful colonial port-city of Singapore, Chinese migrant artists could continue with their artistic experimentations.

In the xieyi (写意) Chinese ink painting tradition, artists were unconcerned with physical likeness. They were focused on capturing the spirit or essence of the subject, which reflected the artist’s temperament and character. Hence, Western modern art with its emphasis on subjectivity rather than objective representation, was consistent with Chinese xieyi principles. Therefore, these artists saw no contradiction between Western and Chinese art, and sought to integrate both.

Due to China’s turmoils in the 1930s and 1940s, some artists migrated to Nanyang where overseas Chinese communities had long existed. With the establishment of the People’s Republic of China by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 1949, artists in China were expected to create works with a national character, addressing social and political concerns before individual needs. Western-influenced art, emphasising individual subjectivity and bearing foreign associations, was considered divorced from the people, and the modern art movement gradually lost momentum in China.

However, in the relatively more peaceful colonial port-city of Singapore, Chinese migrant artists could continue with their artistic experimentations. Local schools provided employment for art teachers. Art societies offered platforms for exhibitions and artistic exchange. Books and information on world art were readily available. As a result, life in Singapore did much to consolidate their understanding of Western art and increase their exposure to a wider range of ideas and concepts than would have been possible in China.

Such artistic innovations in Singapore were also fostered by the socio-political developments of the period. In the lead-up to Singapore’s independence through a merger with Malaya in 1963, there were many calls for a new culture and identity to unite the disparate ethnic communities in Singapore.

Commentators promoted the idea of a new “Malayan” art form that reflected the ideals of a future nation. Many held that the new art form should be a fusion of different cultural styles. For instance, Lim Hak Tai, the influential founding principal of Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts, was quoted in 1950 as saying that “I can teach a student to paint in Eastern styles, I can teach him in Western styles. He learns all ways, and then it’s up to him to experiment and develop his own style. In Malaya, the styles can mix.”

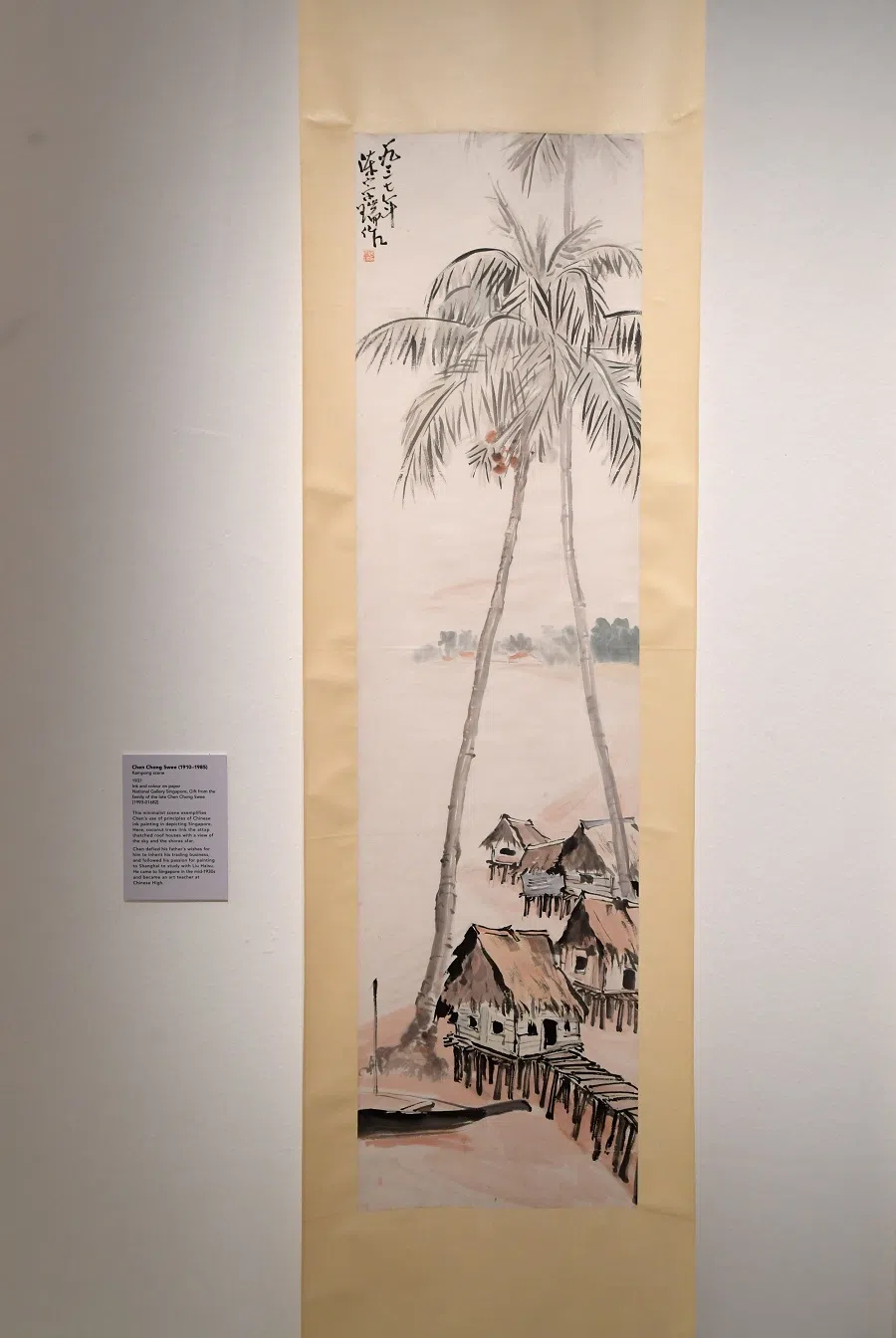

That was how the Nanyang art movement took shape in Singapore. Among the Nanyang artists, there were considerable experimentations in both the ink and oil media. For instance, artists like Chen Chong Swee incorporated Western fixed-point perspective and use of shadows in their works, which are traits not usually found in traditional Chinese ink paintings. Others like Chen Wen Hsi used their understanding of Western modern styles like Cubism and Abstraction to create unconventional compositions for their ink paintings.

There were similarly innovative approaches in oil paintings. For instance, Cheong Soo Pieng favoured the prominent use of black lines and thin washes of colour to imbue his oil paintings with the airy mood associated with xieyi landscapes. Others like Yeh Chi Wei incorporated archaic-style Chinese inscriptions in their oil paintings, to convey the flavour of ancient ink rubbings.

Singaporean art historian T. K. Sabapathy described such cross-cultural “fusion” works as “scroll meets easel” — a synthesis of techniques and styles from the Shanghai School tradition in Chinese ink painting and the School of Paris movement.

Rise of social realist art

However, local artists did not only produce such “fusion” Nanyang works then. A prominent concurrent development was the emergence of artists with social realist inclinations.

... many young artists in 1950s Singapore were strongly influenced by contemporary developments in China where realistic works with strong social content formed the dominant discourse.

Even as China-born artists like Cheong Soo Pieng found acclaim for their formalistic innovations, they were also teaching younger artists, most of whom were born or had grown up in Singapore. Hence, their students’ world views were shaped by their experiences in colonial Singapore, rather than China. For these younger artists, while some emulated their teachers, others sought to use art to effect social change, notably advocating for Singapore’s independence from British rule.

In particular, the founding of the People’s Republic of China by the Chinese Communist Party in 1949 inspired many in Southeast Asia who sought to break free from colonial rule after the end of the Second World War. Therefore, it was unsurprising that many young artists in 1950s Singapore were strongly influenced by contemporary developments in China where realistic works with strong social content formed the dominant discourse.

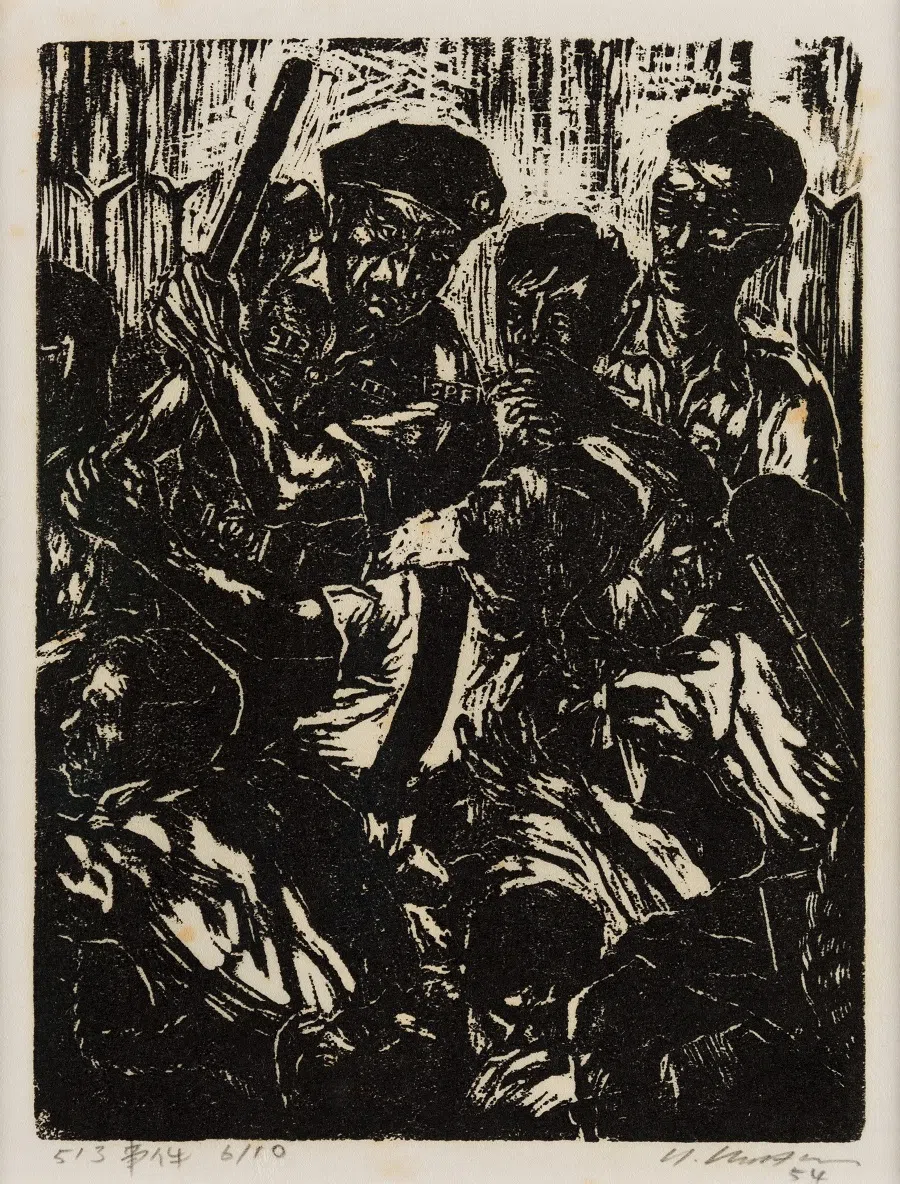

They started producing realistic works showing the injustices of colonialism, particularly the plight of the poor and working classes. For instance, artists like Choo Keng Kwang and Tan Tee Chie created works that commented on the many student and worker-led strikes of the period. Apart from works for exhibitions, artists also produced woodcut prints which could be widely disseminated as illustrations in newspapers and other publications.

For these young artists, such realistic works were a more truthful way of representing life in Singapore. Their heroes were not 20th century modern art icons like Picasso and Matisse, but artists among the 19th century Russian Realists such as Ilya Repin and Vasily Perov who had rejected the conservative attitudes of academic painting in favour of depicting the actual realities of their country.

In Singapore, young artists then organised themselves into groups which promoted art as form of social commentary, such as the Chinese High Schools’ Graduates of 1953 Arts Association (星洲一九五三年度华文中学毕业班同学艺术研究会) and the Equator Art Society (赤道艺术研究会).

In particular, the former was inspired by the “Thirteen Contestants”, a group of Russian students who had resigned from their academy in 1863 to protest against their annual art competition topic for being too removed from the contemporary realities of Russia. These “Thirteen Contestants”, which included artists such as Ilya Repin and Vasily Perov, then formed the Society for Wandering Exhibitions in 1870 which organised mobile exhibitions of realistic portrayals of Russian middle-class and peasant life.

In 1956, the Singapore Chinese High Schools’ Graduates of 1953 Arts Association organised a similar travelling art exhibition which was shown in Singapore, Kuala Lumpur and Penang. Over 17 days, more than 20,000 visitors saw the show where Chua Mia Tee’s Epic Poem of Malaya, were among the works which drew much attention. Chua’s 1955 painting injected a strong sense of nationalist sentiments, through its stirring depiction of a group of young students listening intently to an earnest young man reciting a poem on Malaya.

![Chua Mia Tee, Epic Poem of Malaya, 1955, Oil on canvas, 105.5 x 125 cm, Collection of National Gallery Singapore. This work has been collectively adopted by [Adopt Now] supporters, © Chua Mia Tee and family. (Image courtesy of National Heritage Board)](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/36a9585eb46679ae0c8eb221d2e07c14591eea9eca55e0802cfcbd28fa40dae4)

After the association was dissolved by the colonial authorities in 1956, a few of its members went on to set up the Equator Art Society in the same year. They included young artists like Lim Yew Kwan (son of Lim Hak Tai) and Chua Mia Tee who had studied under teachers such as Lim Hak Tai and Cheong Soo Pieng. While the older artists were supportive or had no objections to their students’ social realist works, it was clear that the motivations of the younger artists were at odds with the formalistic inclinations of their teachers like Cheong Soo Pieng who regarded art-making primarily as a means of self-expression rather than effecting social change.

In contrast, younger Singapore artists like Chua Mia Tee were influenced by writers such as leftist art theorist Wang Zhaowen (王朝闻) who advocated the importance of first-hand experience of daily life in order to create compelling art. Equator Art Society member Tong Chin Sye recalled reading Chinese translations of textbooks by Russian artists which taught that art should reflect society.

Such an ethos corresponded with the Equator Art Society’s approach of organising experiential learning sessions for aspiring artists to work alongside labourers and fishermen to better understand their lives, said artist Loo Ching Ling in a 2003 essay.

... social realist artists soon fell out of favour in the early 1960s when the government started clamping down on left-wing groups which were against Singapore’s merger with Malaya.

In the early years after Singapore gained self-governance in 1959, the new local government was initially open to social realist works, and was supportive of left-leaning anti-colonial organisations like the Equator Art Society. For instance, then Minister of Culture S. Rajaratnam had officiated at the society’s well-attended second annual exhibition in 1960, and commended the artists’ efforts in creating Malayan art.

In fact, Rajaratnam liked Chua Mia Tee’s “National Language Class” painting so much that the artist eventually gifted it to the minister who then hung the work at City Hall. Chua’s painting depicted the determination of a group of Chinese students learning Malay, the new national language. The subject matter resonated with the government’s desire to promote a common Malayan identity, in preparation for Singapore’s full independence through merger with Malaya.

However, social realist artists soon fell out of favour in the early 1960s when the government started clamping down on left-wing groups which were against Singapore’s merger with Malaya. That culminated in Operation Coldstore in 1963, which led to the arrests of more than 100 individuals with suspected communist ties, including Equator Art Society members.

Over time, fewer artists produced social realist works, and fewer people wanted to be associated with such artists and arts groups. In addition, after the 1964 racial riots and Singapore’s painful separation from Malaysia in 1965, the government placed much emphasis on maintaining social stability. Social realist artworks highlighting suffering, unemployment and poverty of the common people, or criticising government policies were deemed by the authorities to be unconducive for building social cohesion and consensus.

... the dichotomy between older artists producing “fusion” Nanyang works and younger artists creating social realist paintings should not be overstated.

In contrast, artists like Cheong Soo Pieng continued to find support for their “fusion” Nanyang works in the post-independence years. This was understandable given that multiculturalism was regarded as a key tenet of Singapore’s national identity by the government. This was best exemplified by the words of founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew when he declared in 1965 that, “We are going to have a multi-racial nation in Singapore. We will set the example. This is not a Malay nation; this is not a Chinese nation; this is not an Indian nation. Everybody will have his place: equal; language, culture, religion.”

No easy categorisations

However, the dichotomy between older artists producing “fusion” Nanyang works and younger artists creating social realist paintings should not be overstated.

Among the older artists, there were those who preferred representational art. For instance, Chen Chong Swee had argued that art needed to relate to its audience. For him, Expressionist, Abstract and Surrealist style works were incomprehensible without their titles. Hence, it would be impossible for viewers to be moved by such works. Similarly, Nanyang Academy’s principal Lim Hak Tai was supportive of the idealistic pursuits of his former students including those who had set up the Equator Art Society.

After all, Lim himself was no stranger to such young idealistic fervour, having taken part in anti-Japanese war resistance efforts in Singapore in the lead-up to the Second World War.

These older artists had also produced works with social commentary. However, unlike the younger artists who tended to create explicit and emotionally charged works, the older artists’ works were often rendered more ambiguous by Western modern styles like Cubism and Abstraction or the conventions of Chinese ink painting.

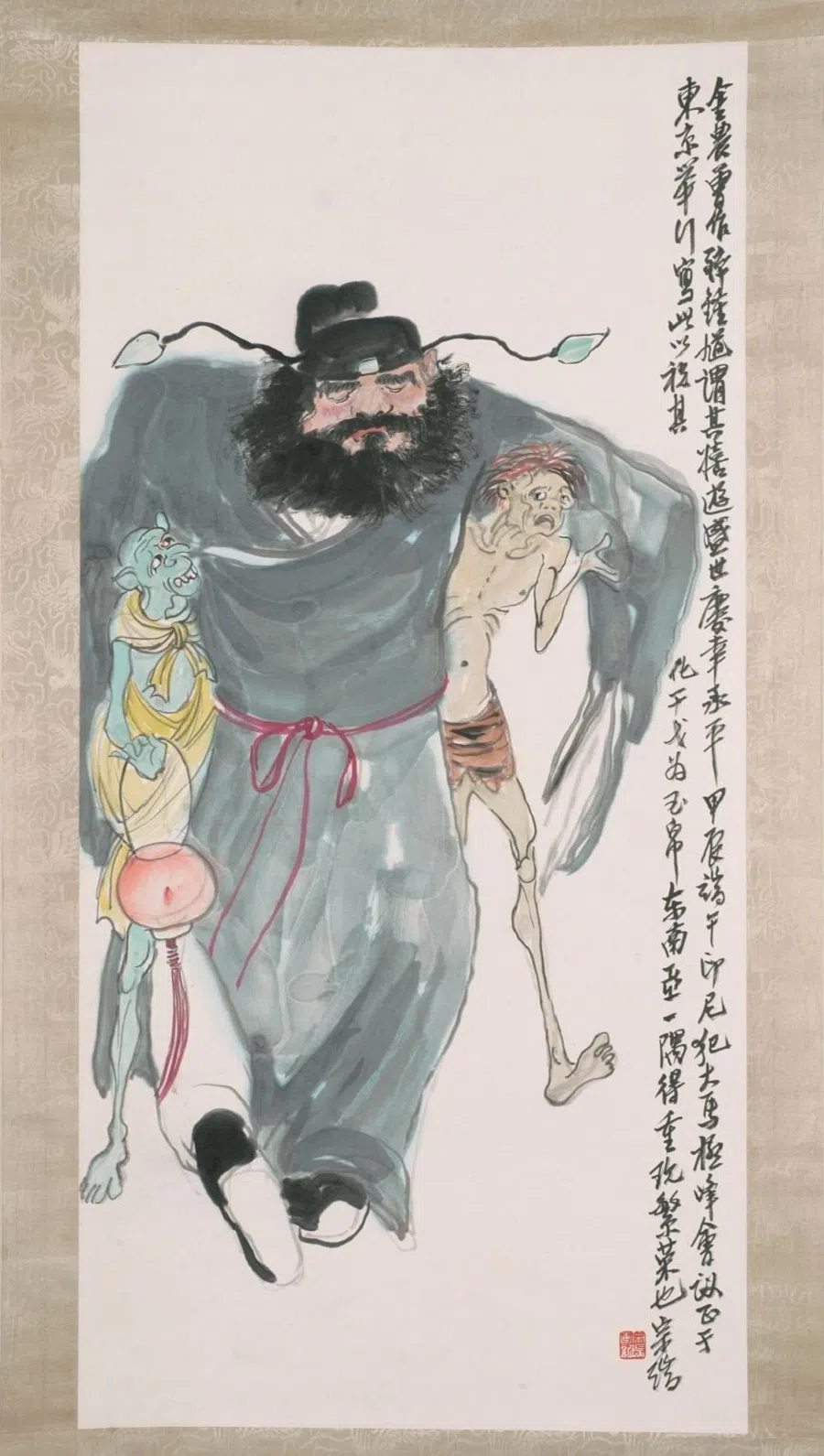

For instance, Lim Hak Tai used a semi-abstract style to produce his oil painting Riot which captured the chaotic protests led by students and trade unions in the mid-1950s. Similarly, Chen Cheong Swee created a conventional ink painting of the legendary ghost catcher Zhong Kui with an unusual inscription referring to the Konfrontasi — a period in the early 1960s when Indonesia waged a low-level war against Malaysia.

Such artistic strategies meant that these older artists’ works did not attract the attention of the colonial authorities then which deemed anti-colonial content as subversive.

... in 1964, seven young artists set up the Modern Art Society, which held that art was about subjective expression through formal elements like lines, strokes, structures and colours, and not about representation of objective reality, likeness or meaning.

Rise of modern art

Similarly, not all young artists in Singapore were pursuing social realist art. Some were more interested in art as a form of personal expression. For instance, in 1964, seven young artists set up the Modern Art Society, which held that art was about subjective expression through formal elements like lines, strokes, structures and colours, and not about representation of objective reality, likeness or meaning.

Their first exhibition of the Modern Art Society in 1963 garnered considerable public attention. As an exhibition that focused on non-representational art, it was considered by reviewers as “revolutionary” and a “landmark in the modern art movement in Singapore”. One of the society’s founding members Ho Ho Ying held that “modern art” (现代画) or “non-objective art” (非形象绘画) was the universal art language of his generation. In his opinion, modern art had to make a break with the past and become relevant to contemporary life, by producing something new.

As he eloquently argued in 1963, “Strictly speaking, Realism has passed its golden age; Impressionism has done its duty; Fauvism and Cubism are declining. Something new must turn up to succeed the unfinished task left by our predecessors. Any attempt to recover our past glory shall be in vain, because history will not repeat. The social backgrounds and thoughts of the past ages have no similarity with that of the present days. We can only repeat old stories on stage, but never in real life. We do not mean to belittle the achievement of traditional art, but we certainly do not agree with those who stick to the old course.”

Finally, it should also be noted that artists did not always fit neatly into categories like “social realists” or “modernists”. For instance, Modern Art Society’s founding member Tay Chee Toh saw no irreconcilable conflict between the two groups of artists. Although working mainly in abstraction, he also admired realist works and had attended the exhibitions held by Equator Art Society.

Regardless of their ages and backgrounds, they sought to create works that best reflected their life in and aspirations for Singapore, be it through Nanyang, social realist or modern art.

Conclusion

In the years leading to Singapore’s independence in 1965, the lively art scene and market was supported by a growing network of art teachers and students, exhibition venues, art societies and art promoters.

Apart from the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts, art was taught in the local schools, and less formal classes were available in organisations like the YMCA Art Club and the Singapore Academy of Arts. During that period, groups like the Society of Chinese Artists, Society of Malay Artists (Persekutuan Pelukis Melayu) and the Singapore Art Society organised frequent exhibitions for their members to show and sell their works. In 1955, the University of Malaya even opened an art museum and hired Dr Michael Sullivan to teach art history.

The “astonishing” awakening of interest in the visual arts in post-war Singapore, especially the high number of exhibitions, led Sullivan to observe in the article “Ten Years of Singapore Art” (1956) that “not even the most cynical could say that Singapore has no art of its own”.

As local artists adjusted to their evolving new identities in the heady years of 1950s and 1960s, they clearly shared similar intentions. Regardless of their ages and backgrounds, they sought to create works that best reflected their life in and aspirations for Singapore, be it through Nanyang, social realist or modern art.

![[Big read] Paying for pleasure: Chinese women indulge in handsome male hosts](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/c2cf352c4d2ed7e9531e3525a2bd965a52dc4e85ccc026bc16515baab02389ab)