Absolute cuts, ambitious aim: Can China lead on climate?

China’s 2035 pledge to cut emissions by 7–10% is more than climate policy — it’s a statement of power at COP30, signalling its ambition to shape global governance, says EAI deputy director Chen Gang.

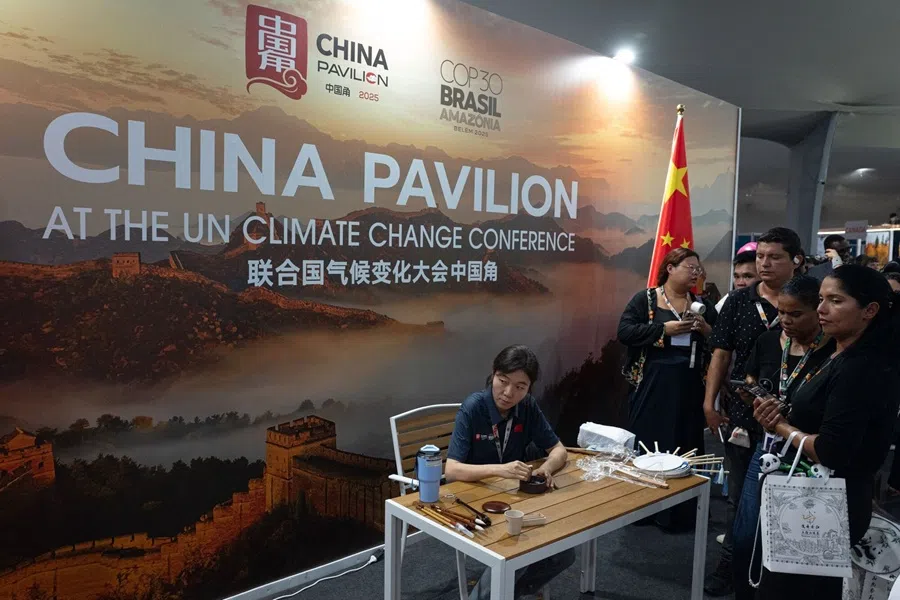

At the 30th Conference of the Parties of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP30) in Brazil in November 2025, China emerged as a central player in the global fight against climate change, especially with the US absent from the COP for the first time in three decades.

With its rising carbon emissions, China is still not ready to take up global climate leadership. Yet top Chinese leaders view China’s high-profile pledges as an effective tool to demonstrate that China is a responsible big power (负责任大国) that may one day assume global governance leadership. China understands that its acceptance of international environmental norms and support of the Paris Agreement and COP meetings can enhance its soft power.

From intensity to absolute cuts

China’s recent climate pledge to reduce carbon emissions by 7-10% from peak levels by 2035 is a critical development in global climate policy, given China’s status as the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases. This pledge represents China’s first absolute emissions reduction target towards its net-zero target, marking a significant shift from its previous intensity-based targets, which focused on reducing emissions per unit of GDP. The pledge is in addition to China’s broader “dual carbon goals” (双碳目标), which include peaking CO2 emissions by 2030 and achieving carbon neutrality by 2060.

... emission control, along with GDP growth and social stability, became an important key performance indicator for officials at provincial, municipal and county levels, affecting their promotion and demotion in the state apparatus.

Chinese President Xi Jinping announced this 2035 climate target on 24 September 2025, prior to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s proposal of the next Five-Year Plan at the fourth plenum in October and the COP30 summit in Brazil in November. The target, aimed at fulfilling China’s commitment to set five-year Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement, will have a significant impact on China’s economic trajectory, energy transition and international image in the next decade.

China’s last set of NDCs was first announced at the United Nations General Assembly in 2020 and adopted as official domestic policy dubbed as “dual carbon goals” in 2021. After that, emission control, along with GDP growth and social stability, became an important key performance indicator for officials at provincial, municipal and county levels, affecting their promotion and demotion in the state apparatus.

China’s commitment comes at a time when global climate efforts are intensifying, particularly following the Paris Agreement, which aims to limit global warming to well below 2°C, ideally 1.5°C, above pre-industrial levels. The International Energy Agency has emphasised that achieving these global temperature goals is not plausible without China’s active participation. This pledge aligns with these objectives, although some analysts view it as modest, suggesting that a higher reduction percentage would be necessary to meet global climate targets effectively.

... Xi now views China’s high-profile climate pledges as an effective tool to demonstrate that China is a responsible power that one day may assume global governance leadership.

China’s ambition of becoming a global governance leader

The global climate leadership landscape has been in flux, particularly since the US’s withdrawal from the Paris Agreement under the Trump administration. This shift left a leadership vacuum that many expected China to fill, given its significant investments in renewable energy and its ambitious net zero goal.

Since President Xi came to power in 2012, due to the urgency of the global climate crisis and China’s domestic pollution situation, the country began pondering aggressive mitigation commitments. At the 2015 Paris climate summit, China pledged to peak its emissions by 2030, deviating from its decade-long insistence on the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities” — used by China and many developing countries to bargain for exemptions from quantitative emission reduction obligations.

With significant progress in China’s efforts to curb pollution, Xi now views China’s high-profile climate pledges as an effective tool to demonstrate that China is a responsible power that one day may assume global governance leadership. Xi, the most powerful Chinese leader since Mao Zedong, called for China to “lead the reform of the global governance system” and to transform institutions and norms in ways that reflect Beijing’s values and priorities.

Xi unveiled the Global Governance Initiative (GGI) to the world in September 2025. The GGI complements the Global Security Initiative (GSI), the Global Development Initiative (GDI) and the Global Civilisation Initiative (GCI) proposed by Xi in the past few years. In explaining the GGI, Xi said “global governance has come to a new crossroads”, focusing on “taking real actions” and “practising true multilateralism”.

By announcing the GGI and 2035 climate target almost at the same time, Xi was implying China’s intention to assume global governance leadership by making more environmental commitments. It’s time for China to take real actions to curb emissions and practice true multilateralism to enhance climate cooperation.

Achieving the new target will require significant reforms in China’s energy sector and broader economy, which however, may not occur until after 2035.

Challenges and criticisms

Despite the positive step, the pledge has faced criticism for its perceived lack of ambition. Analysts and environmental groups have suggested that a 20-30% reduction would be more appropriate to meet global climate targets.

The pledge’s effectiveness is further complicated by the undefined “carbon peak”, which adds uncertainty regarding the baseline from which reductions will be measured. Optimistic projections suggest China could reach peak emissions as early as 2025, but conservative estimates place this around 2028, with emissions potentially reaching 14.5 to 15.5 GtCO₂e (gigatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent).

While China has made remarkable achievements in the development of renewable energy like wind, solar and hydro power, the pace of structural changes needed to fully transition away from coal is far from satisfactory. Despite pledges to halt overseas coal projects, domestic coal burning still accounts for more than half of China’s energy consumption and two-thirds of its electricity output.

This reliance on coal poses a challenge to China’s ability to drastically reduce emissions and transition to cleaner energy sources. Achieving the new target will require significant reforms in China’s energy sector and broader economy, which however, may not occur until after 2035. This timeline raises questions about China’s ability to lead global climate efforts in the near term.

China’s international climate cooperation, particularly with the US, the EU and Japan, is crucial for improving its image and potentially seeking global leadership. However, the current geopolitics and trade tensions among major powers may not be favourable to international climate engagement. The international community will continue to closely watch China’s foreign policy, as its relationship with major powers will have significant implications for global cooperation against climate change.

Companies will need to align with stricter environmental regulations and reporting requirements, focusing on energy efficiency and low-carbon technologies.

Renewable energy and economic implications

China’s climate strategy also includes increasing the share of non-fossil fuels in its energy mix to over 30% by 2035 and reaching 3,600 gigawatts of installed wind and solar capacity by 2035, more than six times the 2020 level. China plans to increase total forest stock volume to over 24 billion cubic metres by 2035. This shift will not only support emissions reduction but also enhances energy security and self-sufficiency, crucial for China’s long-term economic stability.

For businesses operating in China, the new climate pledges signal a tightening regulatory environment. Companies will need to align with stricter environmental regulations and reporting requirements, focusing on energy efficiency and low-carbon technologies. This transition presents both challenges and opportunities, as businesses that adapt early to these changes may gain a competitive advantage in a decarbonising economy.

China’s climate-related investment has been largely driven by a top-down approach from central authorities, promoting renewable energy and emission-cutting technologies. This approach has led to a competitive manufacturing sector that has helped reduce the prices of clean energy equipment, fostering a renaissance in clean energy both domestically and internationally. The development of a market-based green financial system is crucial for achieving China’s new climate target by 2035. This involves reallocating resources to clean and green industries from polluting ones and establishing an adequate incentive mechanism for environmental pollution liability insurance.

China has been developing its carbon emission trading market, a policy tool to control greenhouse gas emissions based on a market-based mechanism. This market internalises carbon emissions as part of companies’ operating costs, guiding them in selecting cost-effective carbon reduction methods. The new emission target demands higher carbon prices and further development of the nascent carbon trading market. The marketised carbon pricing mechanism can help promote the capital flow to the low-carbon field, encouraging enterprises to develop low-carbon technologies and apply low-carbon products.

A window of opportunities

All in all, China’s pledge to cut carbon emissions by 7-10% by 2035 is a critical component of its next-decade climate strategy, reflecting a commitment to more tangible climate action. While the target may not fully satisfy global expectations, it represents a significant policy shift towards absolute emissions reductions.

The success of this pledge will depend on China’s ability to peak emissions soon and accelerate its transition to renewable energy. Given the country’s central role in global climate efforts, China is facing a window of opportunities to turn international pressure into an impetus for climate leadership in global governance.

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)