[Big read] Can China use rare earths to checkmate the US?

Though China and the US are currently holding each other in check through tariffs and export controls, China’s rare earth dominance might just give it a vital edge over the US in the end game, says Lianhe Zaobao correspondent Sim Tze Wei.

As the tariff war rages on between China and the US, the rare earths versus chips battle is happening simultaneously. It is a battle that shows how technology and natural resources have become key bargaining chips in the rivalry between superpowers, and has once again put the spotlight on a previously little-known industrial feedstock — rare earths.

“The Middle East has oil, China has rare earths.” According to media reports in China, this was what Deng Xiaoping, the chief architect of China’s reform and opening up, once said in 1992.

Deng might not have foreseen how well his words would age. 33 years on, rare earths have now become the trump card in the geopolitical standoff between China and the US.

The rare earth issue seems to have reached a turning point.

China-US tensions heighten over rare earths

After China and the US caused global alarm by imposing increasingly high tariffs on each other at the start of April, a consensus was reached on 12 May in Geneva. The US was set to lower tariffs on China from 145% to 30%, while China was set to cut them from 125% to 10%. Both countries agreed on a 90-day tariff truce, and said they would continue to put together a high-level task force to advance trade negotiations.

But on 30 May, barely 30 days into the truce, US President Donald Trump abruptly changed his mind, posting on social media that China had “totally violated its agreement”. In a media interview, US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent said China was “withholding some of the products that they agreed to release during our agreement”.

China’s Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) responded by blaming the US for “baselessly accusing China of violating the consensus, which gravely deviates from the facts”, while the Ministry of Foreign Affairs accused the US of spreading disinformation.

Both China and the US disagreed on the extent to which China would lift all restrictions on the export of rare earths. While the US argues that China agreed to roll back all export restrictions, MOFCOM contends that administrative approval is still required.

Another trigger in the battle over rare earths for China is the US export ban on chips. The Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) in the US Department of Commerce announced on 13 May that using Huawei’s Ascend AI chips anywhere in the world is a violation of US export controls, leading China’s MOFCOM to respond harshly, saying the US move “deprives other countries of their right to develop advanced computing chips and high-tech industries such as artificial intelligence.” Following that, the US introduced further measures, including stopping the sales of electronic design automation (EDA) software for semiconductors to China.

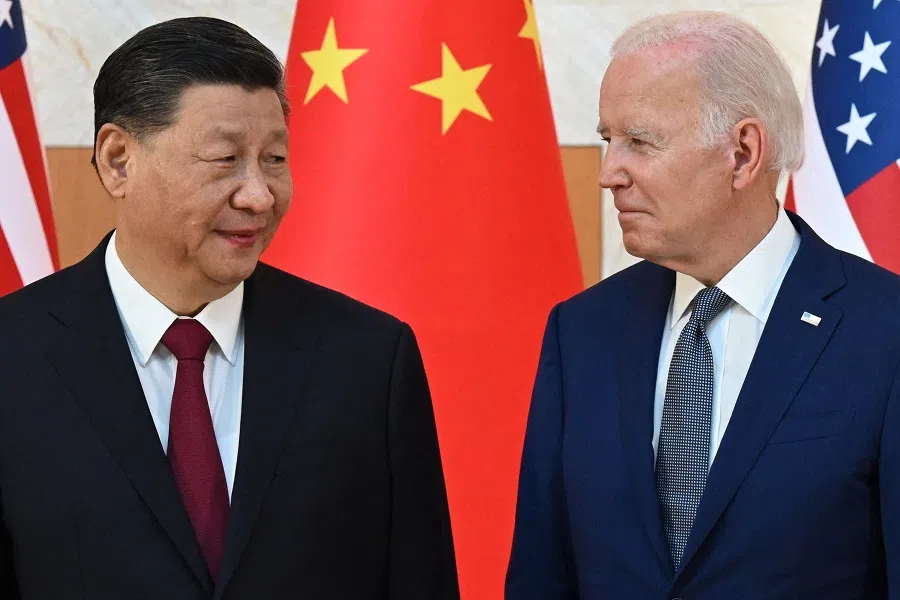

While both countries continued to trade barbs over topics including trade, rare earths, chips and visas for Chinese students, the leaders of both countries spoke over the phone on 5 June. The phone call temporarily cooled temperatures on both sides, and they agreed to hold another round of discussions as soon as possible. (NB: The two sides met soon after in London on 9-10 June to further their talks.)

The rare earth issue seems to have reached a turning point. Trump posted on social media after the call, declaring, “There should no longer be any questions respecting the complexity of Rare Earth products.”

According to estimates from the International Energy Agency (IEA), China produces 61% of the global supply of rare earths, and the processing and refining output is even higher at 92% of the global supply.

China tightens rare earth chokehold on the US

However, the rest of the world is of the view that even if the current conflict on rare earths abates for now, China will still use this leverage to tighten its chokehold on the US moving forward. This essential trump card is only possible because of China’s unshakeable monopoly of the rare earths supply chain.

According to estimates from the International Energy Agency (IEA), China produces 61% of the global supply of rare earths, and the processing and refining output is even higher at 92% of the global supply. The United States Geological Survey (USGS) reported that between 2020 and 2023, around 70% of the rare earth compounds and metals in the US were imported from China, including those used in the military industry, which relies heavily on rare earths from China.

The battle of rare earths and chips that has arisen from the tariff war between China and the US shows how technology and natural resources have become key bargaining chips in the rivalry between superpowers; it has also, once again, put the spotlight on rare earths, a previously little-known raw material essential in industrial manufacturing.

Rare earth elements have outstanding lighting, conduction, magnetic and catalytic properties, among other physical properties.

What are rare earths?

Rare earth elements have outstanding lighting, conduction, magnetic and catalytic properties, among other physical properties. There are two types of rare earths, classed according to their atomic weight: heavy rare earths and light rare earths. Heavy rare earths are scarcer, and many heavy rare earth mines are found in China.

The rare earths are a family of 17 elements, each with different uses. They are vital components of semiconductors, as well as electric vehicles, mobile phones and other tech products. Their military uses include upgrading the performance of missiles and metallic alloys used in tank manufacturing.

In the previous trade war between China and the US during Trump’s first presidency, China did not use rare earths as leverage. This time round, however, China’s previous trade negotiator, Harvard graduate Liu He, has been replaced with Vice-Premier He Lifeng, a China-trained economist who has taken a tougher and different approach against the US.

To counter the high US tariffs, China imposed export controls on seven types of medium and heavy rare earths in early April. China also placed 28 US entities on its Export Control List, prohibiting Chinese exporters from exporting dual-use (civil and military use) items to them. Most entities on the list were American aerospace and defence enterprises.

Following trade talks in Geneva, China’s MOFCOM stated that exporters looking to export dual-use items to any of the 28 listed entities could apply to do so, and that “the ministry will review applications in accordance with laws and regulations, and permits will be granted for those that meet the requirements”.

In other words, China had switched from an outright export ban to an “approval upon review” approach, and did not completely roll back administrative requirements. Sources have divulged that each approval takes 45 working days. Some analysts thus believe that China can use this opaque approval process to control the quantity and speed of rare earth exports.

Beijing has also learned that the way to deal with Trump is “not through submission or concessions, but through deterrence and negotiation”, which explains why rare earths have become a bargaining chip. — Wen-Ti Sung, Fellow, Global China Hub, Atlantic Council

Why play the rare earth card now?

As to why China decided to use rare earths as leverage this time round, interviewed experts agree that China is prepared for a protracted trade war. Since this will be a prolonged battle, China will need to gather more leverage to play the long game; rare earths are one such trump card.

Wu Xinbo, professor and dean at the Institute of International Studies and director at the Center for American Studies in Fudan University, told Lianhe Zaobao during Trump’s first term that China had “put its hopes on resolving the tariff war quickly through negotiations”, and did not wish to play the rare earths card to avoid complicating matters further. At the time, the US had not yet imposed such harsh measures on Chinese technology.

Wu pointed out that China had already started using rare earths as leverage during Biden’s term, when President Biden sanctioned several Chinese technology firms in his focus on the tech sector. China had realised then that the US would try to suppress Chinese tech over the long term, and no longer harboured hopes of an amicable resolution.

“In a sense, China abandoned its illusions and began using the rare earth card during Biden’s term, a strategy it is continuing in Trump’s second term.”

Wen-Ti Sung, a fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Global China Hub, described China’s attitude during Trump’s first term as hoping for a lucky break while avoiding real confrontation.

He said China had believed at the time that Trump’s trade sanctions were only temporary, and that making compromises on specific areas could prevent a trade war. Armed with the experience of dealing with President Trump during his first term, China has now concluded that the trade war will in fact be a long, drawn-out process of continuous confrontation. Beijing has also learned that the way to deal with Trump is “not through submission or concessions, but through deterrence and negotiation”, which explains why rare earths have become a bargaining chip.

... the threat that China’s rare earth card poses is weaker than it was five or six years ago, because more and more countries have accelerated the establishment of their own rare earths industrial chain.

How effective is the rare earths card?

However, Sung assessed that the threat that China’s rare earth card poses is weaker than it was five or six years ago, because more and more countries have accelerated the establishment of their own rare earths industrial chain. While China still dominates, its stronghold has weakened somewhat.

But Wu Xinbo is of the view that rare earths are still an effective leverage over the US, as Washington would not have been so anxious to set up negotiations with China. Nor would they have shown such frustration when its rare earth supply was on the verge of being cut.

Zhu Feng, professor and dean of the School of International Studies at Nanjing University also agrees that export controls imposed by Beijing have indeed exerted pressure on the US and its allies.

One example is American carmakers’ recent complaints that they are facing impending plant closures because of the shortage of rare earth magnets. As they produce 90% of the world’s rare earth magnets, China has a stranglehold on the carmaking supply chain.

... restricted products could still end up getting exported in one way or another due to trade loopholes. Despite export restrictions, for instance, US chips still found their way to China. It is also highly probable that China’s rare earths will also find their way to the US through a variety of alternative channels. — Associate Professor Li Minjiang, RSIS, NTU

China-US contest hinges on their global alliances

The way China is using rare earths as leverage resembles how the US has been playing its chip card, as both approaches share the same underlying logic and strategy.

Li Minjiang, associate professor of International Relations at Nanyang Technological University (NTU)‘s S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), said the strategies of both nations are indeed similar. One similarity is the fact that restricted products could still end up getting exported in one way or another due to trade loopholes. Despite export restrictions, for instance, US chips still found their way to China. It is also highly probable that China’s rare earths will also find their way to the US through a variety of alternative channels.

This is because of the vast number of trading parties and networks globally, which is accompanied by a corresponding number of loopholes. The US will also be able to purchase Made in China industrial products from third-party countries, before disassembling them and extracting the rare earth compounds.

The effectiveness of China’s rare earths card depends on America’s ability to acquire the material from China and transport it to the US via a third-party launderer.

Both Li and Sung pointed out that in the crucial moments of the China-US conflict, the party with the widest circle of friends and allies would have the upper hand. As Sung explained, “It depends on how many friends can help you with laundering.”

Li is of the view that the US has the advantage because it has a wider network of friends. Most buyers of large volumes of rare earths are developed economies such as EU countries and Japan, most of which are American allies. Sung, on the other hand, feels that Trump’s unpredictability might have eroded any advantage the US might have had with its network of friends. “Some may feel that the risk of doing business with the US is bigger than that of doing business with China,” he said.

China can track the whereabouts of its rare earths after they have been exported. Once a third country selling the material to the US has been identified, an export ban for the country will be imposed. — Ding Yifan, Senior Fellow, Institute of World Development, Development Research Center of the State Council

How far will China go to plug trade loopholes?

As to China’s rare earths making their way into American hands, Wu Xinbo is insistent that loopholes do not currently exist. Chinese firms all have to send in their applications to MOFCOM for export permits before they can export any material, and all information has to be stated explicitly, he said.

“Export destinations and end-user details have to be clearly stated, to prevent cases where the items are exported to Europe in name but are actually just transiting to the US,” he said. “So you have to state the information clearly, and then MOFCOM can decide whether to grant approval.” Wu added that the measure was in fact copied from the US.

Ding Yifan, senior fellow and former deputy director of the Institute of World Development under China’s Development Research Center of the State Council, said China can track the whereabouts of its rare earths after they have been exported. Once a third country selling the material to the US has been identified, an export ban for the country will be imposed. He suggested that China could set strict conditions for the sale of rare earths, and that the export of rare earths would be prohibited except under special circumstances.

China has played the rare earths card before. In response to a maritime dispute in 2010, China drew global attention by imposing a ban on exports of rare earth metals to Japan for seven weeks.

Li Minjiang observed that China is unlikely to take the extreme measure of imposing a blanket ban, as that would trigger a backlash from Japan, Korea, and countries in Europe, which would lead to increased pressure from these countries on China. He believes that China is also not likely to go to the extent of tracing all rare earth exports to target the US; though they could technically do so, execution costs would be high and it would be difficult to plug all loopholes, as there are simply too many international buyers and sellers. “It’s hard to imagine MOFCOM keeping tabs on thousands of companies every single moment,” he said.

Wen-Ti Sung also concluded that China’s use of its rare earths trump card is “not to deal a knockout blow to the US”, but as deterrence and a means to secure a more favourable position in negotiations.

China cracks down on smuggling of rare earths

More than a decade ago, rare earths smugglers in China were rampant, undermining the effectiveness of the country’s export controls. This time round, China has tightened controls to guard against the illegal outflow of rare earths.

Securities Times reported that China’s Office of the National Export Control Coordination Mechanism recently issued and implemented a national directive titled “Strengthening the Overall Deployment of Whole-Chain Control of Strategic Mineral Exports”. The directive mandates enhanced supervision of the entire supply chain for rare earths and other minerals, from exploration and mining to export.

In the next stage of trade talks between China and the US, the prevailing view is that the US will request China to lift all export controls on rare earths and other critical metals. Meanwhile, China will try and get the US to loosen export controls on high-end chips, which are critical for China’s military and AI development.

Authorities in provinces such as Guizhou, Hunan, Guangxi, Guangdong, Jiangxi and Yunnan have also declared their commitment to executing the national strategy for the mining and export of critical minerals.

A report in Hong Kong-based publication Asiaweek quoted a reliable source as saying that Lan Tianli, who was chairman of China’s Guangxi Autonomous Region, was investigated while in office for serious transgressions like his involvement in illegal mining and trafficking of national strategic resources. His violations were so severe that they were characterised as treason by the top leaders of the Chinese Communist Party.

A return to the status quo?

In the next stage of trade talks between China and the US, the prevailing view is that the US will request China to lift all export controls on rare earths and other critical metals. Meanwhile, China will try and get the US to loosen export controls on high-end chips, which are critical for China’s military and AI development.

As to how the rare earths vs chips battle will evolve, Wu Xinbo said if each party could take a step back, both would benefit, but he also was of the view that US control over chip export “will only get tighter, not looser”.

Wen-Ti Sung expects that aside from rare earths and chips, both sides will announce tariffs on other industries in the next two to three months. But he believes that these will mostly be performative.

“When the two sides finally stumble towards a deal, both sides will lift those sanctions and claim victory, saying that they have successfully persuaded the other side to lift the sanctions, even if these sanctions never really existed from the beginning and if everything just returns to the status quo.”

US attempts to break free of China’s rare earth monopoly

During his first term, Trump realised that China possessed a key advantage in the geopolitical rivalry between China and the US because they had a chokehold on the global supply chain for minerals, including rare earths. China’s position posed a huge risk for US military and industrial development — a risk so huge it could threaten American national security.

In 2020, Trump used the country’s reliance on foreign sources for critical minerals (including rare earths) as a reason to declare a national emergency and invoke the Defense Production Act to accelerate the development of mineral resources in the US.

In a bid to free itself of China’s monopoly, Trump also set his sights on Ukraine and Greenland.

As the tariff war between China and the US escalated, the US signed an agreement with Ukraine on 30 April to jointly develop Ukraine’s energy and mineral resources. Trump has also announced his intentions to buy Greenland several times, because the territory is rich in rare earth deposits.

The Biden administration also saw the formation of the US-led Minerals Security Partnership (MSP) with 13 US allies and EU members, focused on building a diversified supply chain for critical minerals.

... the main difference between China and the US lies in China’s longstanding government-led industrial policy. — Assistant Professor Tom Özden-Schilling, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, NUS

Eroding China’s rare earth monopoly is no easy feat

Tom Özden-Schilling, assistant professor of Sociology and Anthropology at the National University of Singapore (NUS), pointed out that rare earths are not necessarily scarce, but they are difficult to mine and process. He is currently studying the global expansion plans of Australia, Malaysia and the US in the exploration and scientific development of critical minerals.

Özden-Schilling said the main difference between China and the US lies in China’s longstanding government-led industrial policy. The Chinese government supports businesses, allowing them to operate at all levels of the supply chain — even at a loss — while also building up reserves. Although the US also once had a state-led industrial policy for rare earths, this policy was abandoned after the work was outsourced. Without government support, it is difficult to establish a domestic supply chain to meet the country’s own demands.

Currently, even the only operating rare earth mine in the US in Mountain Pass, California also sends its ores to China for processing.

China’s long-term monopoly over the global supply chain also means that it can easily undermine new rivals by dropping rare earth prices. New projects are ultimately unable to compete with such low prices. “Americans, Australians, and Canadians complain about that,” Özden-Schilling said. “China is essentially forcing all of these other projects and all these other countries to do what they did for several decades, which is to operate at a substantial loss in order to get started.”

He added that unless the US government and businesses made undergo a major psychological shift — becoming more patient and accepting that substantial profits will not happen in the short term — it would be hard to imagine China’s rare earth monopoly changing within his lifetime.

... the US is still a decade away from securing rare earths independently from China. — Cory Combs, Associate Director, Trivium China

Can China deliver a checkmate?

Li Shou, director of China Climate Hub at US think tank Asia Society Policy Institute, said China’s dominance over the rare earth supply chain is hard to overturn. It would require a continuous and comprehensive strategy spanning years that would involve foreign diplomacy, trade, and other matters. Most crucially, government intervention will be essential to support the establishment of the industry.

Bloomberg cited Cory Combs, associate director at Trivium China (which focuses on supply chain research), as saying that the US is still a decade away from securing rare earths independently from China. Meanwhile, Chinese firms have already developed viable replacements for most of American chips. “China is gaining ground in the standoff,” he said.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “晶片围困华 稀土将军美”.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)