[Big read] Colluding in deceit: Will PwC get a second chance in China after the Evergrande scandal?

PwC in China has come under hot water after being implicated in the Evergrande fraud scandal. Lianhe Zaobao senior correspondent Chen Jing speaks with experts to find out if and how this Big Four accounting firm will recover from this debacle.

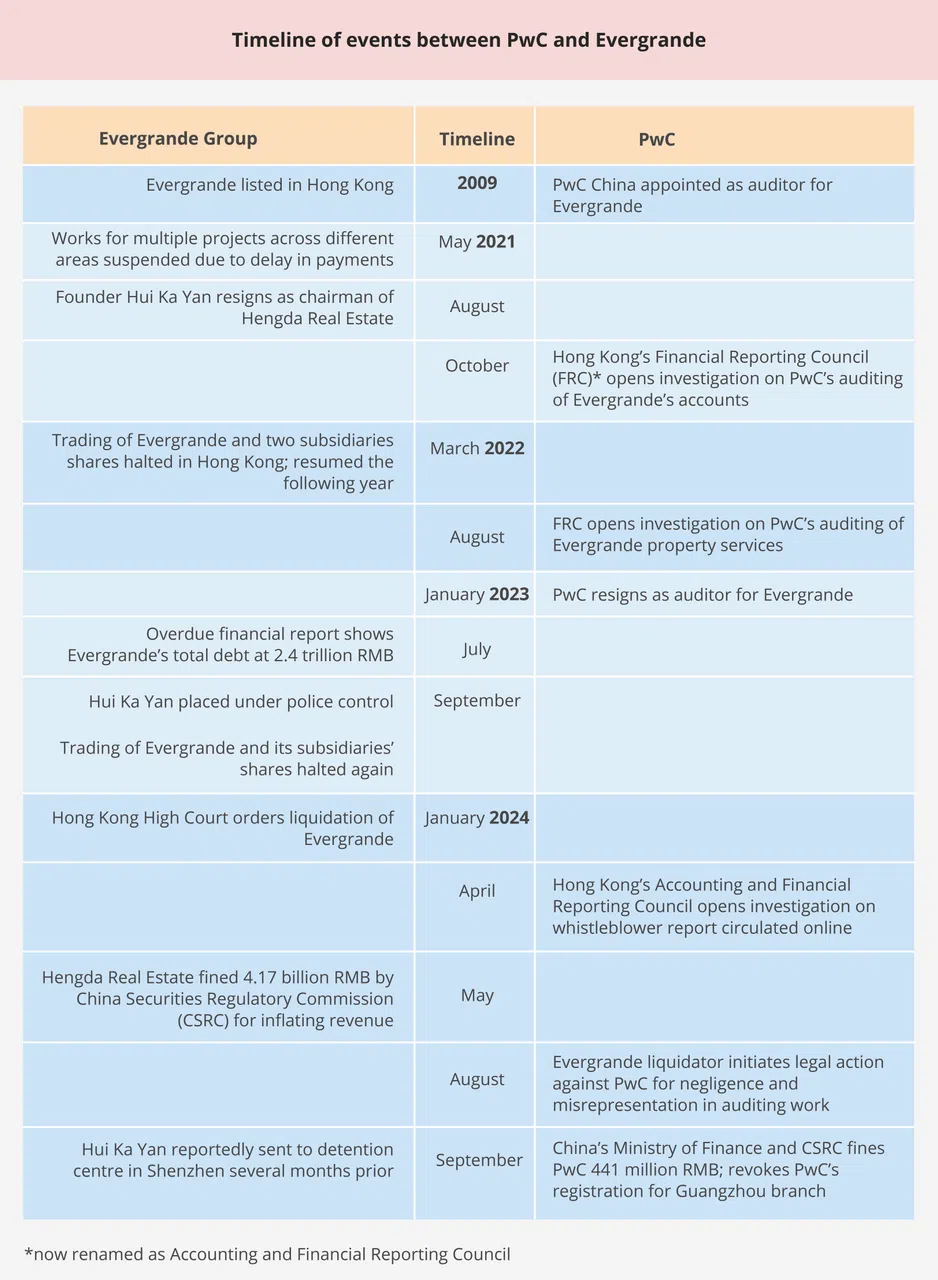

Following the collapse of Chinese real estate giant Evergrande, its long-time auditing partner, PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) also finds itself in the dock.

On 13 September, China’s Ministry of Finance (MOF) and Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) imposed a record fine of 441 million RMB (US$62.2 million) on PwC, while PwC’s Chinese subsidiary, PwC Zhong Tian, faces a six-month suspension and revocation of the licence for its Guangzhou branch. Eleven registered accountants involved in the case were also penalised, with four losing their licences.

This is the most severe punishment meted out to a multinational auditing firm in China, stemming from Evergrande’s shocking financial fraud scandal.

In January, Hong Kong-listed Evergrande was ordered to liquidate, leaving behind a staggering debt of over US$300 billion, 1.6 million unfinished housing units, and billions of US dollars worth of defaulted wealth management products.

PwC had to a certain extent covered up and even condoned Hengda’s financial deception and fraudulent bond issuance.

The CSRC’s investigation revealed that between 2019 and 2020, Evergrande’s main subsidiary Hengda Real Estate (hereafter Hengda) falsely inflated its revenue by 564 billion RMB and profits by 92 billion RMB by recognising revenue in advance, setting a global record for financial fraud.

As Evergrande’s external auditor, PwC bears significant responsibility. During its 14-year tenure, PwC consistently issued “unqualified opinion” on Evergrande’s annual reports, indicating no major errors in the financial information.

Uncovering Evergrande’s financial crisis

It was not until PwC ended its partnership with Evergrande in 2023 and was replaced by Prism Hong Kong and Shanghai that the truth behind the developer’s financial crisis was revealed. Evergrande’s re-released 2021 and 2022 financial reports showed that the company’s total liabilities exceeded 2.4 trillion RMB, indicating insolvency.

The CSRC said that PwC “turned a blind eye” to Evergrande’s financial fraud, and that it was not merely a case of auditing negligence, but rather PwC had to a certain extent covered up and even condoned Hengda’s financial deception and fraudulent bond issuance.

The MOF listed six “sins” by PwC in its penalty document, including severe flaws in audit procedures for Hengda; lack of independence; assisting Evergrande in falsifying consolidated financial statements to inflate profits; and failing to identify significant errors in financial reports and hiding or concealing them through various means.

So, what drove it to take such a huge risk and condone, or even facilitate, Evergrande’s financial deception?

Peng Shugang, a lawyer at China Commercial Law Firm (Shanghai), told Lianhe Zaobao that the penalty document from the MOF used the phrase “aware of” 21 times and “should have known” five times, while the CSRC’s penalty statement used the phrases “failed” or “completely failed” five times. Indeed, both agencies believe that PwC’s actions in auditing Hengda showed obvious intentional wrongdoing and gross negligence.

Professor Mak Yuen Teen of the National University of Singapore (NUS) Business School said that the regulatory accusations suggest that it was not just a case of audit failure due to a failure to follow proper audit procedures or exercising professional scepticism, but that of “collusion with the client and likely not limited to just a few staff”.

UK-headquartered PwC is one of the Big Four accounting firms and the highest-earning auditing institution in China in 2022. So, what drove it to take such a huge risk and condone, or even facilitate, Evergrande’s financial deception?

Taking a chance too many

In April this year, a whistleblower letter circulating online pointed fingers at Raymund Chao, then chair of PwC China. The open letter, signed by “some PwC partners”, alleged that Chao led the firm into the fire pit of Evergrande in the pursuit of high income; previous partners wanted to drop Evergrande ten years ago, but this was blocked by Chao.

Chao is a former partner of American accounting firm Arthur Andersen, once the world’s largest accounting firm but had collapsed in 2002 due to its involvement in the Enron scandal.

Although PwC denied the allegations, due to the severity of the accusations, Hong Kong regulators launched an investigation into PwC’s audit of Evergrande, which is still ongoing.

A former PwC employee in Beijing told Lianhe Zaobao that Chao was responsible for securing the Evergrande account. The person shared, “Many partners apparently advised against taking the project because Evergrande chair Hui Ka Yan is a wildcard. But I understand why they made the decision. At the time Hui was one of the richest people in China, and landing his project would greatly boost the company’s brand and revenue.”

He continued, “Auditors know that all listed companies have issues to some extent. For a major client like Evergrande, there was a low risk that things would explode, while profits were guaranteed.”

According to database platform Wind, Hengda paid PwC some 288 million RMB in audit fees over 14 years.

The open letter highlighted that Chao is a former partner of American accounting firm Arthur Andersen, once the world’s largest accounting firm but had collapsed in 2002 due to its involvement in the Enron scandal. Most of its employees and projects were absorbed by PwC, which now finds itself in a similar predicament two decades later.

Shen Meng, a director at Chanson & Co, analysed when interviewed that the entanglement between PwC and Evergrande is the same as that between Arthur Andersen and Enron. Evergrande paid substantial audit fees to PwC, which selectively ignored the developer’s abnormal development amid external competition and internal performance pressures.

He said, “Big corporations like PwC don’t normally err knowingly. It may have taken a chance, believing that Evergrande’s problems would naturally resolve over time. Little did it expect Evergrande to be the first property developer to fall when the Covid-19 pandemic triggered an economic downturn and a downward spiral in the property market.”

The tide has gone out, and Evergrande, which has been swimming naked, and its fig leaf, PwC, are now both exposed. Preventing similar events from happening again is a challenge that extends beyond China.

Evergrande, which operates on a high-debt, high-leverage business model, unquestionably crossed the “three red lines” drawn by the government to reduce the debt risk of real estate enterprises in 2020, and its financial crisis snowballed. Evergrande founder Hui Ka Yan, who led Evergrande out of danger several times, could no longer save the company. It was reported in September that Hui, who was once China’s richest person, had been moved to a special detention centre in Shenzhen months ago.

The tide has gone out, and Evergrande, which has been swimming naked, and its fig leaf, PwC, are now both exposed. Preventing similar events from happening again is a challenge that extends beyond China.

Zhao Lei (pseudonym), who has worked at both KPMG and PwC, thinks that even if another firm had handled the issue, it may not have performed better than PwC. “Compared with local Chinese firms, the Big Four have done relatively well in terms of compliance and independence. While auditors on the frontline will definitely report any issues, the outcome depends on the negotiations between the partners and the client’s top management,” he noted.

Ensuring independence and impartiality

China Commercial Law Firm’s Peng pointed out that avoiding conflicts of interest in the audit process is key to ensuring independence and impartiality in the auditing process. This can be done via measures such as regularly rotating audit partners and teams, as well as establishing business firewalls between audit and non-audit services.

For example, audit reform measures introduced by the EU in 2016 require large listed companies to change their audit firms every ten years to minimise conflicts of interest arising from long-term collaborations. The EU also restricts audit firms from providing services to clients that may lead to conflicts of interest, such as tax advisory and compliance services, as well as financial system design and implementation.

NUS’s Mak analysed that while rotating auditors after a certain number of years or engaging two auditors simultaneously helps avoid conflicts of interest, it can be costly. In addition, the consulting fees earned by the Big Four outstrip the fees from audit services, which may compromise audit quality.

He added that strong regulatory supervision of audits and imposition of severe penalties for blatant misconduct will have to be part of the solution. “The action that China has taken is something that other countries should follow in cases of auditor misconduct,” he noted.

“When things go wrong in other lines of business, it’s us on the finance side who become the scapegoat. I heard that nearly half of the staff in the finance teams in Beijing and Shanghai have been let go.” — Zhao Lei (pseudonym), a former PwC employee

Suffered a setback but will not collapse

A year before Chinese regulators hit PwC with a suspension and fine, Zhao Lei, who was working at the Shanghai office, received a retrenchment notice.

The 30-year-old told Lianhe Zaobao that rumours of layoffs had circulated internally last September, and his manager had later notified him that his contract would not be renewed when it expires in February this year.

Although Evergrande was not mentioned during the meeting, many speculated that the layoffs were related to the Evergrande incident. What puzzled Zhao was that he was neither at the Guangzhou office handling Evergrande’s business nor responsible for real estate audits.

“When things go wrong in other lines of business, it’s us on the finance side who become the scapegoat. I heard that nearly half of the staff in the finance teams in Beijing and Shanghai have been let go,” he said.

In July, PwC launched yet another round of layoffs in China. Bloomberg reported that at least 100 employees at PwC China’s offices in Beijing, Shanghai and other locations are being let go. With regulators hitting a record fine on PwC, nearly 20,000 PwC employees in mainland China, including over 700 at the Guangzhou office, could be affected by the Evergrande incident.

Attacked from all sides

Just as PwC is laying off employees, it is also being dismissed by clients. Incomplete statistics show that since the CSRC revealed in March that Hengda was suspected of financial fraud, at least 60 companies have terminated their cooperation with PwC, including large state-owned enterprises (SOEs) such as the Bank of China, China Life Insurance and PetroChina with annual audit fees of 20 million RMB or more. The audit fees of the Bank of China alone amounted to 193 million RMB.

As Evergrande’s shares are traded in Hong Kong, PwC will continue to face investigations by Hong Kong regulators, along with subsequent civil claims. In August, Evergrande liquidators sued PwC for negligence and misrepresentation in handling the developer’s auditing work. Evergrande bond investors are also understood to be preparing to file a lawsuit against PwC.

Industry insiders believe that while the Evergrande incident is not severe enough to lead PwC down the path of collapse, as was the case for Arthur Andersen years ago, the reputation of this audit giant will undoubtedly be severely damaged, with effects extending beyond China.

Shen of Chanson & Co analysed that following the closure of its Guangzhou office, PwC’s operations in southern China will face a gap, impacting the firm’s business strategy in China. However, as PwC also has offices in Beijing, Shanghai and Shenzhen to share the workload, “the likelihood of a complete collapse due to this incident is quite low”.

“It will take PwC a long time to regain trust, especially in China.” — Professor Mak Yuen Teen, NUS Business School

Another accountant who previously worked at PwC in Beijing pointed out that although PwC’s suspension will last only six months, the penalties would prevent them from participating in bids for SOE projects for the next three years. The person added, “Non-state clients may return as early as next year, but the same can’t be said for state-owned clients for the next five years. PwC might no longer be the leading firm in China after losing so many big clients.”

NUS’s Mak cited the example of PwC’s involvement in the tax leak scandal in Australia in 2023, which not only impacted its business in Australia, PwC’s global reputation also took a hit. At the same time, the impact of the Evergrande fraud incident could extend beyond China.

He added, “It will take PwC a long time to regain trust, especially in China.”

In early September, PwC Singapore extended its temporary practice licence in mainland China for six months. Analysts believe that this was for the ease of supporting PwC’s operations in China during its suspension.

On the day that Chinese authorities announced the heavy penalties for PwC, the firm’s internal memo to employees pointed out that the PwC network is making tangible investments to ensure high-quality and sustainable operations in China.

Efforts needed to reshape brand image

Yet at the same time, the Wall Street Journal reported that PwC would conduct a large-scale global retrenchment for the first time in 15 years, affecting around 1,800 employees. Thus, the ability of PwC headquarters to provide assistance to its business in China has also been called into question.

“PwC would have to dedicate even more resources to strengthen internal controls and risk management, and make great efforts to rebuild its brand image and regain market confidence.” — Peng Shugang, Lawyer, China Commercial Law Firm (Shanghai)

China Commercial Law Firm’s Peng believes that the two administrative penalties will have a comprehensive impact on PwC’s operations in China. In the short term, revenue would decline sharply, and the company would lose both clients and talents; while in the long term, there would be damage to brand image, obstruction to expansion of operations, as well as increased challenges to win bids.

Peng added, “PwC would have to dedicate even more resources to strengthen internal controls and risk management, and make great efforts to rebuild its brand image and regain market confidence.”

How did PwC help Evergrande commit fraud?

How did Evergrande commit financial fraud?

The CSRC reported that Hengda inflated its revenue and profits from 2019 to 2020 by prematurely recognising income.

Traditionally, real estate companies waited until a project was completed and delivered to recognise revenue. However, changes to Hong Kong accounting standards in 2017 allowed projects to be recognised as revenue before delivery. Evergrande then significantly lowered its standards, recognising presale income as current revenue, creating an illusion of rapid growth, which it used to support dividends and bond issuance.

In addition to exploiting accounting methods, Evergrande manipulated handover lists and dates in its Ming Yuan system, a cloud service for property developers in China, to fabricate facts among other manipulations. As the property market declined, Evergrande’s approach of “borrowing from Peter to pay Paul” was unsustainable, with multiple projects halted due to overdue payments, in turn exposing the fraudulent activities.

What role did PwC play?

Investigation by China’s MOF and CSRC revealed that PwC was aware of Evergrande’s fraudulent activities during audits, but failed to disclose them and even collaborated with Evergrande to cover them up.

For instance, when selecting properties for random sampling visits, PwC allowed Evergrande to dictate the list, removing projects marked “off-limits” by Evergrande. At one point, 74% of the samples were removed and replaced.

During on-site investigations, auditors found that several properties were not completed, yet the final report did not flag any issues. When regulatory authorities conducted on-site investigations this year, some of the properties were still vacant.

PwC even sent templates of audit working papers to Evergrande, giving them free rein to choose the samples, fill in the sampling results, and even provide corresponding audit evidence.

Additionally, PwC prepared the consolidated financial statements for Hengda from 2018 to 2020 and designed several entries to artificially inflate profits based on Hengda management’s target profit requirements, with most amounts rounded off to hundreds of millions.

How much did Evergrande inflate its revenue and profits with the help from PwC?

The CSRC found that Hengda inflated its revenue by 214 billion RMB in 2019 and 350 billion RMB in 2020, and its profits by 40.7 billion RMB and 51.3 billion RMB respectively.

Statistics showed that in 2019, 50% of Hengda’s revenue and 60% of its profits were falsified. In 2020, nearly 80% of its revenue and almost 90% of its profits were also fraudulent. Additionally, when issuing five corporate bonds between 2020 and 2021, Hengda referenced the inflated data and raised a total of 20.8 billion RMB.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “伴随恒大沉沦 普华永道伤筋动骨”.

![[Big read] Paying for pleasure: Chinese women indulge in handsome male hosts](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/c2cf352c4d2ed7e9531e3525a2bd965a52dc4e85ccc026bc16515baab02389ab)

![[Big read] How UOB’s Wee Ee Cheong masters the long game](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/1da0b19a41e4358790304b9f3e83f9596de84096a490ca05b36f58134ae9e8f1)