[Big read] Singapore’s critical minerals challenge: Small nation, big stakes

As countries vie for control over critical minerals and rare earths, Singapore is rethinking its strategy by diversifying supply, boosting innovation, and exploring its potential as a regional minerals hub. Lianhe Zaobao senior business correspondent Ong Yong Huat discusses the importance of these vital resources and unpacks Singapore’s approach.

Recent news reports on the trade tussle between China and the US have shed light on the topic of critical minerals, underscoring its significance in geopolitical discussions.

For instance, following US engagement in technological and tariff wars, China decided to impose stricter controls on rare earth exports, which led to US automobile manufacturers raising alarms about a potential disruption in parts production. Ford, for instance, was forced to shut down one of its car manufacturing plants in Chicago for a week as a result.

There are quite a few important critical minerals. The US Department of the Interior categorises 50 minerals as critical.

What are rare earths?

Currently, the most well known of these is rare earths, often referred to as “industrial gold”. This term encompasses 17 metallic chemical elements, including lanthanum, cerium and neodymium.

Rare earth elements possess unique optical, electrical and magnetic properties that enable them to combine with other materials to form substances with enhanced characteristics. These elements significantly boost the performance and quality of a wide range of products, making them essential across numerous industries. For example, rare earths improve the strength, durability and heat resistance of steel, aluminium, magnesium and titanium alloys — materials critical to the production of tanks, aircraft, and missiles.

... these non-fuel minerals are either deemed “vital to economic and national security”, possess a high risk of supply chain disruption, or perform an essential function in one or more energy technologies...

In addition to rare earths, critical minerals also include copper, lithium, nickel, cobalt and so forth, which are essential for clean energy technologies such as wind turbines, electric vehicles (EVs) and power grids.

Demand surges for critical minerals amid global green energy transition

The importance of critical minerals lies not in their market size. In fact, compared to the oil market, which is valued in the trillions of US dollars annually, the critical minerals market is relatively small.

However, these non-fuel minerals are either deemed “vital to economic and national security”, possess a high risk of supply chain disruption, or perform an essential function in one or more energy technologies, including technologies for the generation, transmission, storage and conservation of energy.

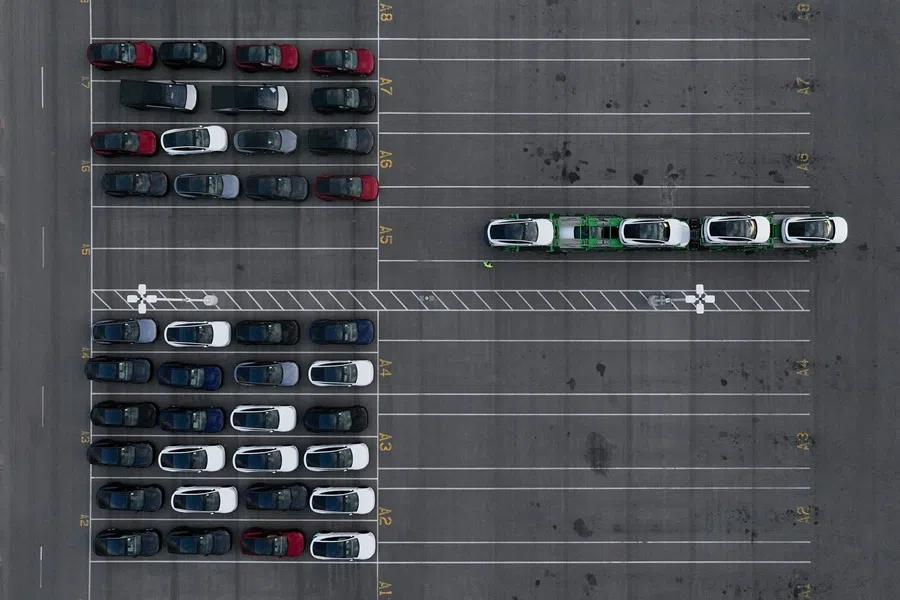

According to data from the International Energy Agency (IEA), the critical minerals market experienced strong growth in 2024, primarily due to the booming EV market. Lithium demand is projected to grow by nearly 30%, while demand for nickel, cobalt, graphite and rare earths increased by 6% to 8%, driving the global critical minerals market size to US$328.2 billion.

By 2032, the market size is expected to hit US$586.6 billion, with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 7.53% from 2025 to 2032.

Jarrod Baker, mining and metals sector leader at Deloitte Southeast Asia, stated in an interview with Lianhe Zaobao that Singapore imported approximately US$1.03 million worth of rare-earth compounds in 2023 (roughly 12 tonnes), primarily from the US, South Korea, Japan, China and Malaysia.

... the mineral resources required for offshore wind plants are 13 times more than that needed for gas-fired plants, and the mineral input for an EV is six times that of traditional cars. — Lim Wei Hung, Executive Director and COO, Southern Alliance Mining

“With Singapore’s push towards EVs, battery storage, and semiconductors, these numbers are expected to grow significantly, especially as local processing and refinement increases.”

Lim Wei Hung, executive director and COO at Southern Alliance Mining, pointed out when interviewed that the global market for critical minerals will further increase alongside the expansion of the scale of clean energy technologies.

Lim said that the mineral resources required for offshore wind plants are 13 times more than that needed for gas-fired plants, and the mineral input for an EV is six times that of traditional cars. As a result, demand for lithium, copper and rare earths is surging, with the critical minerals market expanding at a double-digit pace.

Baker noted that critical minerals play an essential role in the green energy transition. As the global supply of fossil fuels is rapidly decreasing, it is necessary to transition towards alternative energy sources. Producing carbon-free or low-carbon technologies — such as solar panels, wind turbines and battery storage — requires substantial mineral inputs, with demand projected to triple by 2030 and quadruple by 2040 to meet net-zero goals.

Control of mineral supply chains now a bargaining chip

Besides the rapid growth in demand, critical minerals also evidently play a crucial role in politics, especially in geopolitical disputes.

Lim stated that control over the mineral supply chains has become strategic leverage. For example, China’s imposition of export controls on gallium and tungsten has unsettled global markets. Today, supply disruptions are caused not only by geological scarcity, but also by trade disputes.

In fact, the rise of critical minerals was also closely linked to warfare. A century ago, the world used only a few dozen metals; during World War I, the US listed critical minerals for the first time, identifying only five relatively scarce minerals.

Now, the elements used in various world technologies cover the entire periodic table (of over 100 elements), while the list of critical minerals has expanded significantly. Defence systems, telecommunications, semiconductors, high-speed electronic devices, EVs and renewable energy all rely heavily on critical minerals.

Assistant Professor Tom Özden-Schilling from the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at the National University of Singapore said critical minerals as a policy really started in World War II, with US military planning.

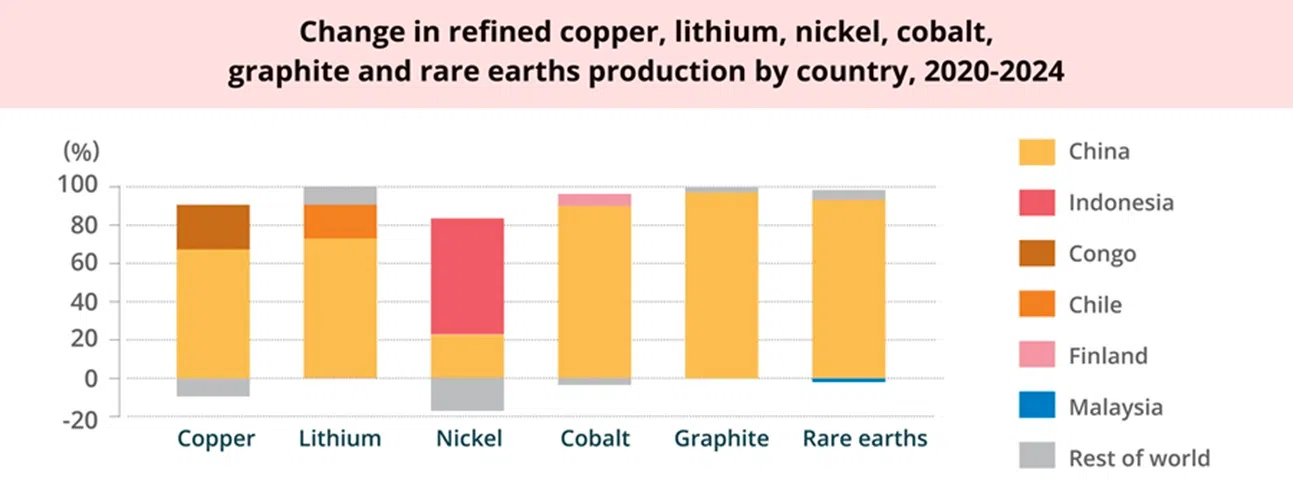

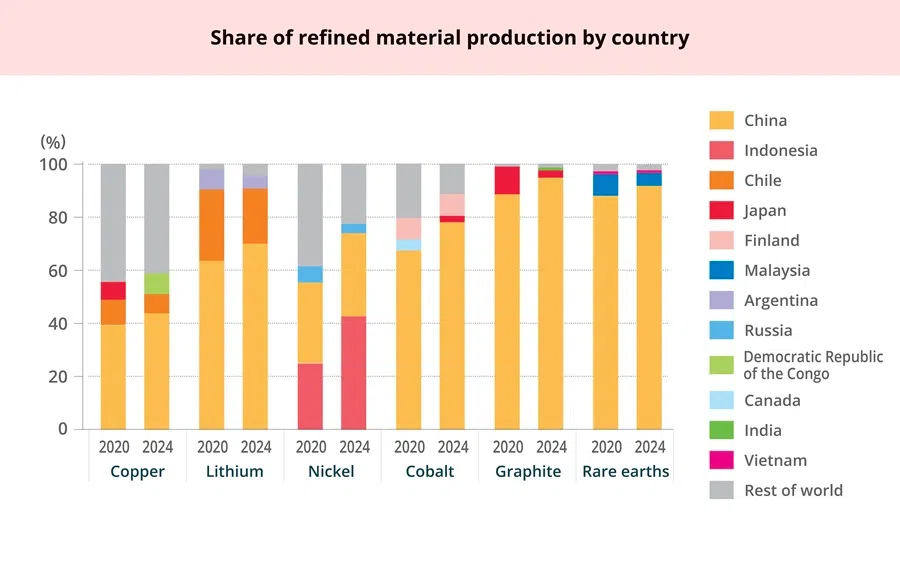

... around 90% of the supply growth comes from the largest single-supplier countries: Indonesia (nickel) and China (cobalt, graphite, and rare earths).

Since the 1990s and 2000s, China began replicating the US approach. During the 2010 China-Japan dispute, China banned the export of rare earths to Japan, prompting Japan to also adopt the US strategy to ensure supply security.

Since then, more and more countries have started to pay attention to the issue of critical minerals and have formulated national strategies accordingly.

Supply shortage risks for energy-related minerals

However, the production and refining of critical minerals remain highly concentrated in a handful of countries.

According to the latest Global Critical Minerals Outlook report by the International Energy Agency (IEA), the average market share held by the top three refining countries for major energy-related critical minerals has risen from about 82% in 2020 to 86% in 2024. Notably, around 90% of the supply growth comes from the largest single-supplier countries: Indonesia (nickel) and China (cobalt, graphite, and rare earths).

The IEA emphasises that there is a risk of supply shortages for these minerals over the next decade, particularly for copper. The report notes that as countries expand their power grids, copper demand is expected to increase significantly. Copper is a key material for electricity transmission and is used in structural frameworks, wiring, cables, transformers, circuit breakers, switches, and substations.

Current projections for copper mining projects suggest that there will be a supply shortfall of up to 30% by 2035.

In addition, 55% of energy-related minerals are subject to various export restrictions around the world. For instance, Indonesia has imposed a total ban on the export of nickel ore. China has also restricted or prohibited the export of certain critical minerals — including seven types of heavy rare earth elements — to the US. These restrictions cover not only raw ores and refined products but also processing technologies.

“The uncomfortable truth is that Western policy on critical minerals is one of the reasons why the West lacks access to them.” — a report by DWS

The IEA’s analysis of 20 energy-related strategic minerals finds that while market sizes may be small for some, disruptions could have outsized economic impacts. “And 15 of the minerals have exhibited greater price volatility than oil.”

A recent report by DWS, the asset management arm of Deutsche Bank, said that outside China, significant mineral deposits are also found in the US, northern Europe, Canada, Mexico and Australia.

“The problem is that the governments of these countries have made it almost impossible to obtain permits for development projects. Either the approval periods are far too long or projects are blocked completely… The uncomfortable truth is that Western policy on critical minerals is one of the reasons why the West lacks access to them.”

The report says: “The concentration of mineral extraction and processing in a small number of countries, as well as long lead times for the development of new mines, pose significant risks to supply chains worldwide. Excessive dependence on high-risk countries such as China for critical minerals also creates significant political and economic risks. Interruptions in supply or shortages cannot be ruled out. An effort to diversify supply chains is intended to remove this risk, but diversification cannot be achieved quickly.”

The report concludes that “rising geopolitical tensions complicate the task of sourcing critical minerals for the global energy transition and are making them the focus of not only political but also social interest. Critical minerals can be seen as the Achilles’ heel of the energy transition.”

In the energy sector, delays in adopting solar, wind and EV technologies due to rare earth shortages could slow Singapore’s green targets. — Lim

Mineral supply chain disruptions could affect multiple sectors in Singapore

If the supply chain of critical minerals is disrupted, whether due to trade tensions, environmental bans, or geopolitical factors, it could trigger a chain reaction that impacts Singapore across various sectors.

Lim Wei Hung noted that in the economic sector, manufacturing sectors dependent on high-tech components may face cost spikes or production delays. In the energy sector, delays in adopting solar, wind and EV technologies due to rare earth shortages could slow Singapore’s green targets.

In the technology sector, semiconductors and sensors essential for AI and smart city applications could become costlier or delayed. In terms of security, as a globally connected city-state, supply chain disruptions can indirectly limit Singapore’s access to defence-grade components.

Lim said: “For example, China’s restriction on tungsten exports in 2024 sent shockwaves through global supply chains. Countries are now exploring alternatives and redundancies — and Singapore will need to stay agile and responsive.”

Baker pointed out that as a global trade hub, Singapore is particularly vulnerable to supply chain disruptions arising from geopolitical developments and may also face pressure from third-party import and export controls.

He said that Singapore’s economic model relies heavily on advanced manufacturing and its role as a global trading and logistics hub — sectors that are heavily reliant on critical minerals as inputs.

Once supply is disrupted, the import prices of critical minerals may rise, increasing production costs for Singaporean companies. These costs could be passed on to consumers, contributing to inflation and potentially weakening Singapore’s tech ecosystem and competitiveness.

With Singapore being a major semiconductor manufacturing hub, disruption of critical minerals like silicon would directly impede chip production and likely decrease national economic growth.

Also, critical minerals are foundational for advanced defence systems — for example, rare earths for magnets in guided missiles, specialised alloys and so on. Disruption could compromise Singapore’s ability to maintain, upgrade, or acquire crucial defence assets.

With Singapore being a major semiconductor manufacturing hub, disruption of critical minerals like silicon would directly impede chip production and likely decrease national economic growth. A shortage of chips would also make it difficult to build and maintain data centres, hampering the nation’s ambitions for AI innovation.

Baker pointed out that a shortage of lithium, cobalt, nickel and graphite — essential for batteries — will severely hinder the adoption of EVs and affect the progress of the Singapore Green Plan 2030.

Managing supply disruptions through diversification

Kelvin Lim, CEO of Singaporean battery manufacturer Durapower, revealed in an interview that apart from occasional price fluctuations due to supply and demand, the company has not faced any supply disruptions for processed materials procured from their supply chain.

“Our supply chain is not dependent on specific suppliers or chemistry, and we have developed alternatives as part of overall risk mitigation,” he noted.

The Singapore representative of GlobalFoundries did not respond to requests for comment in time.

Although Singapore is not a major producer of critical minerals, it can still leverage its existing strengths to address supply challenges and seize opportunities.

For one, supply diversification. Southern Alliance Mining’s Lim Wei Hung said, “As a regional hub for advanced manufacturing, data centres and clean tech investments, Singapore is exposed to supply volatility. Ensuring resilient and diversified access — whether through trade, stockpiling or regional partnerships — is a growing priority.”

By advancing its manufacturing capabilities and focusing on higher-value segments, Singapore can minimise the direct impact of raw material price fluctuations, as the cost of critical minerals would form a smaller proportion of the final product’s value. — Jarrod Baker, Mining and Metals Sector Leader, Deloitte Southeast Asia

Meanwhile, Baker advocates a proactive diplomatic strategy and international partnerships. He said, “Singapore is one of the world’s busiest ports and a key global trading hub, which gives it exceptional access to supply chains and the ability to facilitate mineral trading, storage, and processing services even without domestic mining capabilities. Singapore must actively engage with mineral-rich countries and key players in the critical mineral supply chain to ensure a stable and reliable supply of critical minerals.”

Innovation also key to avoid supply disruptions

Innovation and research and development is another strategy. Lim Wei Hung thinks that Singapore can invest in research and development for material substitution, recycling technologies and circular economy solutions.

On the other hand, Baker pointed out that Singapore can continue to promote a growing green finance sector to support sustainable mining and clean technology. It can also increase its research and development capabilities and innovation clusters focusing on materials science, recycling technologies and alternative materials.

He also thinks that Singapore focuses on high-value-added manufacturing, particularly in electronics, semiconductors, pharmaceuticals and precision engineering, which uses critical minerals in highly refined and specialised forms. By advancing its manufacturing capabilities and focusing on higher-value segments, Singapore can minimise the direct impact of raw material price fluctuations, as the cost of critical minerals would form a smaller proportion of the final product’s value.

Can Singapore become a regional mineral trading hub?

Meanwhile, Lim Wei Hung noted that, like other advanced economies, Singapore can consider stockpiling certain minerals as a buffer. Also, encouraging environmental, social, and governance-aligned sourcing can position Singapore as a trusted hub in minerals trade.

... there is potential for Singapore to become a regional hub for critical minerals trading and certification. Its financial services infrastructure can be leveraged as a platform for critical minerals trade as well. The country can also support investments in upstream projects in resource-rich regions... — Deven Chhaya, Partner, KPMG Singapore

Deven Chhaya, a partner at KPMG Singapore leading infratech advisory services, noted that although Singapore is resource scarce, it has become an oil refining and trading hub. Similarly, it can also position itself as a key player in the critical mineral ecosystem.

He said, “The main challenges lie in the geopolitical sensitivities and trade barriers that affect the supply of these minerals. However, Singapore can leverage its strengths — a stable regulatory environment, and a strong financial services sector with investments and strategic diplomatic relationships with major producers and consumers of critical minerals, to overcome these challenges.”

Chhaya also thinks that there is potential for Singapore to become a regional hub for critical minerals trading and certification. Its financial services infrastructure can be leveraged as a platform for critical minerals trade as well. The country can also support investments in upstream projects in resource-rich regions and promote innovation in mineral recycling and sustainable refining practices.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “关键矿产抢夺战 大国博弈稀土换筹码 我国布局“无矿变有矿””.