Can China save Iraq from its water crisis?

Amid Iraq’s growing water crisis, while Chinese financing and technical expertise can offer short-term relief and help plug Iraq’s infrastructure gaps, such engagement also raises the spectre of new dependencies and opaque decision-making. US academic John Calabrese looks into the issue.

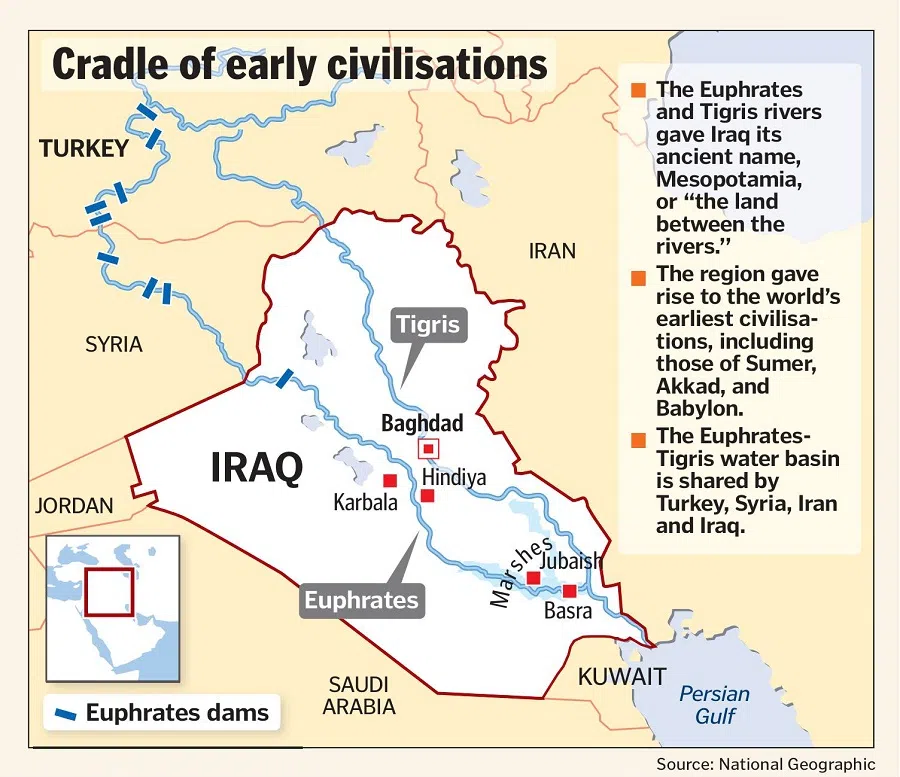

Iraq’s once-mighty Tigris and Euphrates rivers — the lifeblood of early civilisation — have shrunk to a fraction of their historic flow, unleashing drought, crop failures and the retreat of marshland communities from Thi Qar to Muthana. Nowhere is the crisis more acute than in Basra, where saltwater intrusion, pollution and failing infrastructure have turned clean water into a luxury and driven residents to the brink.

Into this vacuum steps China, betting its Belt and Road credentials on megaprojects in southern Iraq. Chinese state firms promise rapid, no-strings-attached delivery — a lifeline for Baghdad, but one that raises pressing questions about debt, sustainability and whether Iraq can convert foreign capital into durable reform rather than temporary relief.

Nearly half of Iraqi families reduced the land under cultivation during the 2024 farming season, with food insecurity worsening as a result.

The national picture: a crisis deepens

The scale of Iraq’s water crisis is staggering. According to UNICEF, average river flows have plummeted, leaving the country in the grip of severe drought. The Tigris and Euphrates river flows have decreased by 40–60% since the 1970s due to upstream damming and climate change, with projections suggesting Iraq’s total surface water could fall to 10-20 bcm annually by 2035, down from 77 bcm in 1980. The Water Stress Index rates Iraq at 3.7 out of 5, among the world’s highest risk countries. Comparatively, Iraq’s per capita water share is now half that of Iran’s, reflecting the scale of the crisis.

Iraq lost 400,000 donums (100,000 hectares) of arable land in 2023 alone, with wheat yields dropping by 50% in drought-affected regions.

This collapse has devastated rural livelihoods. Nearly half of Iraqi families reduced the land under cultivation during the 2024 farming season, with food insecurity worsening as a result. According to ReliefWeb, water scarcity has forced many families to borrow for essentials, cut spending on healthcare and education or deplete savings — placing immense pressure on already vulnerable households. The impact is especially acute in rural areas, where agriculture remains the backbone of local economies.

Groundwater extraction is unsustainable, pollution is rampant and mismanagement — from unauthorised fish farms to unregulated agricultural projects — continues to degrade Iraq’s already fragile water ecosystem.

The crisis is driving a surge in rural-to-urban migration and internal displacement. The Norwegian Refugee Council reports that tens of thousands have been forced to leave their homes due to drought, particularly in southern governorates. As families abandon desiccated farms and marshlands, communal relations are strained in receiving areas, where resources are already stretched thin.

Agricultural production — once Iraq’s rural backbone — is faltering amid chronic water shortages. Traditional irrigation methods, such as flood irrigation, which remain in widespread use, waste up to 70% of water. Groundwater extraction is unsustainable, pollution is rampant and mismanagement — from unauthorised fish farms to unregulated agricultural projects — continues to degrade Iraq’s already fragile water ecosystem.

Iraq’s water infrastructure is in a state of advanced decay. Many treatment plants, pipes and pumps date back to the 1970s and 1980s, with little maintenance or investment since. The International Organisation for Migration (IOM) notes that broken pipes and leaking pumps waste a significant portion of treated water. Meanwhile, untreated sewage and industrial effluent are routinely discharged into rivers, compounding the pollution crisis.

Iraq’s water woes are exacerbated by upstream developments in Turkey, Iran and Syria. The construction of massive dams, such as Turkey’s Ilisu Dam on the Tigris and Iran’s diversion of tributaries, has dramatically reduced the volume of water reaching Iraq. Iraq’s 2023 request to increase Euphrates flows from Turkey to 700 m³/s was rejected; Ankara currently releases only 200 m³/s, down from 950 m³/s in 1980. Iran’s diversion of the Karun River tributary has reduced cross-border flows to Iraq’s marshes by 80%, desiccating 4,000 km² of wetlands.

Saltwater has pushed inland, contaminating both surface supplies and critical aquifers, a dynamic aggravated by rising temperatures and prolonged droughts.

Basra: epicentre of collapse

Basra’s crisis crystallises Iraq’s national water emergency. Situated at the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates — and as the last stretch before the Arabian Gulf — Basra bears the cumulative burden of reduced upstream flows, pollutant buildup, and sea-water intrusion. As freshwaters dwindle, salinity in the Shatt al-Arab reached 28,000 ppm in southern Basra in 2024 — 56 times the World Health Organisation (WHO) safe drinking threshold — rendering 90% of the governorate’s irrigation water unusable. Saltwater has pushed inland, contaminating both surface supplies and critical aquifers, a dynamic aggravated by rising temperatures and prolonged droughts.

The Shatt al-Arab River, formed at Qurna by the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates, is Basra’s main source of surface water for drinking and other uses. However, over the past several years, its water quality has sharply declined. A 2025 study found that water at monitoring stations consistently met only Category V or worse of the Surface Water Environmental Quality Standard — indicating the poorest quality, unsuitable for direct human consumption. Water scarcity and high salinity in Qurna and Shatt al-Arab has reduced crop yields and land under cultivation, in turn generating income losses and increasing household expenses and debt.

Hospital admissions for kidney disease in Basra rose by 72% between 2020 and 2024, linked to prolonged consumption of saline water. When climate stress peaked in 2018, contaminated water hospitalised some 118,000 people and left 90% of residents without safe tap water during the summer months.

Decades of neglect have left Basra’s water treatment and distribution networks in tatters. Broken pipes and ageing pumps squander as much as 80% of treated water, forcing residents onto unreliable — or outright unsafe — alternatives. Water scarcity in Basra not only threatens local livelihoods but also Iraq’s broader economic and social stability, given Basra’s role as the centre of the country’s oil industry and a key population centre.

The crisis extends into Basra’s fields. Salt intrusion has reduced cultivated acreage and slashed harvests, undermining food security and rural incomes. In 2023, over 60% of Basra’s farmers reported total crop failure due to saline irrigation water. Unsustainable practices — monoculture, overgrazing and a near-total absence of drainage canals — have deepened soil salinisation, turning once-fertile plots into fallow land. In April, the Iraqi High Commission for Human Rights warned that elevated salinity poses an “imminent threat” to the Shatt al-Arab waterway — a bellwether for the region’s agrarian collapse.

Social tensions have followed. In July 2024, clashes between the Al-Bu Sultan and Al-Ali tribes in northern Basra killed 34 people over canal access disputes, displacing 2,000 families. Over 55,000 Basra residents were displaced due to water-related conflicts between 2022 and 2025.

Basra’s unravelling — exceptional in its geographic vulnerabilities — exposes the failures of Iraq’s water governance and underscores the urgent need for infrastructure rehabilitation, regulatory reform and sustained investment. Without rapid action, the collapse witnessed here may yet become the blueprint for water-driven instability across the nation.

In response to these converging threats, the Al Sudani government has begun demonstrating a new level of commitment to water policy not seen under past leadership. Recognising the urgency, Baghdad has shifted project oversight from the Ministry of Construction and Housing to the Basra governorate — an attempt to reduce bureaucratic delays and accelerate implementation on the ground.

Yet with Iraq’s institutional capacity still constrained and funding gaps persisting, external actors are becoming increasingly central to the country’s water security efforts.

At the heart of Beijing’s strategy lies energy security: Iraqi oil underpins China’s efforts to diversify away from Saudi, Russian and Iranian suppliers.

China’s calculated intervention: pragmatism meets opportunity

As Iraq confronts these mounting challenges, external actors — particularly China — are stepping in to play a larger role in the country’s water security future. Through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China has become a key development partner in Iraq, funding critical projects in energy, transportation, and increasingly, water management.

At the heart of Beijing’s strategy lies energy security: Iraqi oil underpins China’s efforts to diversify away from Saudi, Russian and Iranian suppliers. Large-scale water projects, most notably the Common Seawater Supply Project (CSSP), directly support Iraq’s southern oilfields by providing the reinjection water critical to boosting and sustaining crude output. By financing and constructing these facilities, Chinese firms safeguard the very oil flows they depend on.

Chinese investment surpasses that of other actors in both scale and scope. In fact, Chinese companies are leading or financing Iraq’s largest water projects. In Basra, Chinese firms have been involved in wastewater treatment upgrades and desalination plant development — initiatives essential to reversing the tide of toxic salinity that plagues the governorate. State-owned Power Construction Company of China (PowerChina) is developing a refinery and partnering with the Al Rida Investment Group to build a desalination plant at the Al Faw Port.

In December 2023, Shanghai Electric secured a contract to develop a seawater desalination plant in southern Basra to tackle a potable water shortage. Chinese firms such as SEPCO, HEWITT and Hutchinson Water International are also moving into Iraq’s desalination market, challenging traditional incumbents and underscoring Beijing’s broader commercial ambitions. China CAMC Engineering Co. (CAMCE) and other Chinese companies are building natural gas processing facilities in southern Iraq, which indirectly support water infrastructure by ensuring steady energy supplies needed for water treatment operations.

China’s state-backed companies offer something Western development partners often cannot: rapid project implementation without conditionalities related to governance or transparency.

China’s signature approach centres on capital-intensive ventures — desalination plants, treatment facilities, and supporting power grids — packaged alongside oil-sector and electrical projects. These megaprojects are typically structured as oil-for-infrastructure deals or long-term contracts with below-market financing.

China’s state-backed companies offer something Western development partners often cannot: rapid project implementation without conditionalities related to governance or transparency. For Iraqi leaders under pressure to deliver quick results in restive areas like Basra, this model — however imperfect — has appeal.

Yet China’s growing role is not without controversy. Critics of China’s infrastructure diplomacy in Iraq warn of debt sustainability, lack of local capacity-building, and opacity in project procurement as risks that could undermine long-term water governance reform.

Iraq’s 2024 Anti-Corruption Commission report found US$1.2 billion in misallocated funds for water projects since 2020, raising concerns about Chinese-funded initiatives. Iraq’s debt to China reached US$12 billion in 2025, with 60% tied to infrastructure projects lacking transparent repayment terms. Only 12% of Iraq’s water sector budget targets technical training, leaving desalination plants dependent on foreign contractors.

Nevertheless, for Baghdad, Chinese investment is increasingly seen as a lifeline in a time of environmental collapse. Beijing’s engagement aligns with its strategic interests in securing influence in a region long dominated by the West and in ensuring the stability of oil-exporting partners amid global energy transitions. Iraq, for its part, hopes to leverage Chinese expertise and capital to address its most urgent infrastructure deficits.

While Chinese financing and technical expertise can offer short-term relief and help plug Iraq’s infrastructure gaps, such engagement also raises the spectre of new dependencies and opaque decision-making.

A cautionary inflection point

Iraq’s water crisis, with Basra as its most glaring expression, reveals the intersection of environmental stress, institutional fragility, and geopolitical contestation. As traditional livelihoods wither and displacement accelerates, the stakes for Iraq’s national cohesion — and for regional stability — continue to rise.

The involvement of outside powers such as China introduces both opportunity and risk. While Chinese financing and technical expertise can offer short-term relief and help plug Iraq’s infrastructure gaps, such engagement also raises the spectre of new dependencies and opaque decision-making. Beijing’s track record in delivering large-scale infrastructure and water management projects gives it a significant role to play — from desalination to smart irrigation — potentially accelerating Iraq’s modernisation beyond what Western donors have so far enabled.

Yet key questions remain: Wwill Chinese-backed initiatives be transparent and aligned with Iraq’s long-term sustainability goals, or will they entrench existing governance failures? Can Iraq’s political system manage these large-scale foreign projects without corruption or misallocation? And how will China navigate the delicate geopolitics of Iraq’s upstream water negotiations with Turkey and Iran?

Ultimately, Iraq must lead its own recovery — investing not just in pipes and pumps, but in governance, accountability, and local capacity. Outside help, including from China, can be part of the solution. But without reforms at home, even the best-funded initiatives may prove short-lived.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)