China’s ‘small’ BRI still thinks big: The return of grand infrastructure

China’s BRI enters a new phase with a softer slogan — “small and beautiful” — but its cross-border rail projects show that big, strategic infrastructure is still very much on track. US academic Chen Xiangming gives his take.

I marked the BRI’s first decade with a lengthy article in the World Financial Review on its defining impact on the formation of a dozen regional economic corridors and subcorridors. While not true of all of them, these corridors are being shaped or enabled by recently constructed or newly connected freight train routes crossing borders.

Rail impact

Broken ground in 2012, completed in 2016 and commercially operational in 2018, the Addis Ababa-Djibouti Railway (ADR) shortens the shipping distance of 750km from three to seven days to 20 hours at two-thirds of the cost. The ADR carries fertiliser, wheat and steel from the Port of Djibouti to Ethiopia while bringing coffee and clothes in the opposite direction. It has facilitated Ethiopian exports from some industrial parks along the rail route and localised operation with over 3,000 trained drivers, conductors and maintenance workers.

Shipping cost from Kunming to Vientiane with extension to Bangkok dropped 30-50% and within-Laos transport cost down 20-40%.

Broken ground in 2016 and commercial operational in 2021, the China-Laos Railway (CLR) ran over 10,000 freight trains carrying 60 million tons of cargo through 22 May 2025. The number of cross-border freight trains rose from two to 18-20 every day, and the type of shipped goods from 80 in 2021 to over 3,000 in 2025. The CLR brings iron ore, cassava and rubber from Laos and durians from Thailand to China while sending China’s manufactured products and Yunnan’s fresh flowers and vegetables to Laos and Southeast Asia. Shipping cost from Kunming to Vientiane with extension to Bangkok dropped 30-50% and within-Laos transport cost down 20-40%.

Major China-built railways like these, including the Nairobi-Mombasa (standard-gauge) Railway and the Jakarta-Bandung high-speed railway, stand out not only for their positive economic impact but for their scale and complexity as massive transport projects.

In addition, they are among the most expensive projects costing US$4-6 billion, financed mostly by the BRI’s two primary policy banks, the Export-Import Bank of China and the China Development Bank. They embody the BRI’s priority on large-scale infrastructure projects, even though thousands of much smaller and more diverse projects have been completed by China over the BRI’s first decade.

Xi’s directive ushered in a new phase to the BRI featuring smaller and more varied projects, especially those with a green and sustainability focus, financed by more diverse and multi-party sources.

What is new about the new BRI?

Beginning around 2017 and continuing through the pandemic, the BRI saw a reduction in infrastructure financing. The official shift in strategy came in 2021, when President Xi, speaking at the Third BRI Forum, emphasised the importance of prioritising “small and beautiful” projects that directly benefit people’s lives. He advocated for leveraging limited funding to achieve greater financial mobilisation in support of practical and “heartwarming” projects.

Whether partly in response to the West’s false narrative of “debt traps”, Xi’s directive ushered in a new phase to the BRI featuring smaller and more varied projects, especially those with a green and sustainability focus, financed by more diverse and multi-party sources. This also involves spinoffs from already completed iconic infrastructure projects like the CLR.

Examples of new BRI projects abound. February 2025 saw the launch of an integrated rural project, funded by moderate loans from the Export-Import Bank of China, that includes the digging of 85 wells, the construction of 89 water towers, 1,450 km of water pipes and 300 water supply stations for 18,200 rural families in northern Senegal.

China Development Bank, in partnership with the State Foreign Economic Activity Bank of Uzbekistan, financed a project to bring several thousand new energy buses to the capital city of Tashkent, with the first batch of 1,000 buses already delivered in 2023.

On 12 October 2023, the Laos Railway Vocational Technology Academy, built by the Yunnan Provincial Construction Investment Co., was inaugurated by the Lao president. With a built-in enrolment of 1,000 students for the next three classes, the academy has added sustainable value to the CLR with the purpose of becoming a base to train future professionals.

... the cumulative number of loans by the Export-Import Bank of China has stimulated additional investment of over US$400 billion through 2024.

The BRI’s new phase has broadened to such “small and beautiful” projects as public housing construction in Ecuador, solar farms in Argentina, waste-water treatment in Egypt, power generation for rural clinics in remote South Africa, and local education and food security in the Republic of Congo.

Projects like these have involved independent and joint financing beyond the two traditional policy banks, by the Bank of China, the Agricultural Bank of China, and China CITIC Bank, in partnership with other national and international banks. The Bank of China, for example, provided credits to 1,200 relatively small BRI projects, while the cumulative number of loans by the Export-Import Bank of China has stimulated additional investment of over US$400 billion through 2024.

The reality, however, is a resurgence of rail projects, albeit with a different approach to funding consistent with the spirit of “small and beautiful”.

Return to rail

With all the new projects above, it seems that the new BRI has moved beyond the construction of major rail projects that overlapped with its first decade. The reality, however, is a resurgence of rail projects, albeit with a different approach to funding consistent with the spirit of “small and beautiful”.

The return to new rail projects reflects the BRI’s continued focus on infrastructure. More importantly, these new rail projects, which have either already broken ground or are soon to do so, reflect China’s geostrategic vision to enhance trade and logistics connectivity. The aim is to forge closer and broader ties between its domestic economy and key trading neighbours and partners further afield.

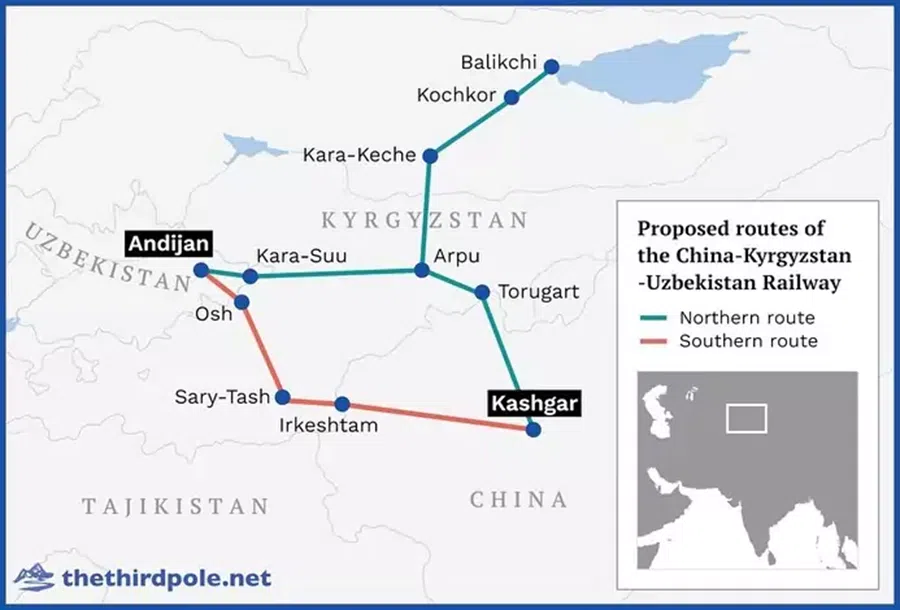

From Kashgar, Xinjiang, to Andijan, Uzbekistan

On 29 April 2025, in Jalal-Abad, Kyrgyzstan, work began to dig three tunnels along a critical stretch of the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan Railway that will link China’s most western city of Kashgar, Xinjiang, to the Uzbekistani city of Andijan, where it enters the national rail system anchored to the capital of Tashkent. The railway’s length of 616 km is split into 213 km in China, 341 km in Kyrgyzstan and 62 km in Uzbekistan.

China has agreed to provide US$2.3 billion of the total price tag of US$4 billion, which falls in the range of costs for the few completed railways under the BRI. The other half of the cost is split among US$1.2 billion from China State Railway Co. and US$572 million from the national railway companies of Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, respectively.

If completed by the target year of 2031, this railway will cover the shortest distance from western China to Europe through Iran and Turkey...

While having a big say on this rail project, China has made a concession to Kyrgyzstan by agreeing to build a facility in Makmal for switching trains from standard tracks from Kashgar to the wider tracks leading to Andijan. This compromise enables Kyrgyzstan to generate revenue from track switching at Makmal, positioning it as a logistics hub that can expand its commercial and industrial activities.

The use of wider gauge tracks in Central Asia is a legacy of the former Soviet Union. The integration of standard and wider gauges at cross-border points highlights Russia’s declining influence in the region. Russia had held a veto over the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway project since 1994. However, in 2022, following its invasion of Ukraine, Russia relented, paving the way for the project to advance swiftly. This shift allowed for the rapid progression through multiple government agreements and a joint feasibility study, ultimately leading to the commencement of construction.

If completed by the target year of 2031, this railway will cover the shortest distance from western China to Europe through Iran and Turkey, opening a new and direct freight route along the BRI’s China-Central Asia-West Asia Economic Corridor.

From Ganqi Maodu, Inner Mongolia, to Gashuun Sukhait, Mongolia

Further north along China’s land border, a new railway will link China and Mongolia through the twin border ports of Ganqi Maodu in Inner Mongolia and Gashuun Sukhait in Mongolia. The two countries will each build their portions of the railway, with a combined investment of approximately US$500 million. This short 8-km railway will feature both standard and wide-gauge tracks, integrating into the respective rail systems jointly operated by both sides. Scheduled for completion by 2027, this railway is designed to ship 55-60% of Mongolia’s coal exports, especially coking coal to China, more efficiently, while also carrying some of Mongolia’s copper to China.

It will replace the century-old meter-gauge railway built by France, enabling more efficient transportation of the growing trade between China and Vietnam.

From Kunming, Yunnan, to Haiphong, Vietnam

A new railway is planned across the China-Vietnam border, stretching from Kunming through the twin border cities of Hekou and Lao Cai, extending to Hanoi and the port city of Haiphong. Spanning approximately 390 km and featuring standard tracks compatible with China’s rail system, this railway is projected to be completed by 2030.

It will replace the century-old meter-gauge railway built by France, enabling more efficient transportation of the growing trade between China and Vietnam. This is particularly beneficial for the shipment of industrial parts and components among the many manufacturing companies that have established production facilities in northern Vietnam, especially around Haiphong, which has seen recent port capacity expansions.

China has agreed to provide a loan of US$5.35 billion, accounting for 64% of the projected cost of US$8.3 billion. This level of Chinese financing is comparable to the range of US$4-6 billion for the few completed BRI rail projects. It is a sign of this new railway’s geostrategic significance, given China’s most recent high priority on strengthening relations with its neighbouring countries.

‘Two-Ocean Railway’ across South America?

From China’s neighbouring regions to South America, another ambitious cross-border rail project is underway. This railway initiative dates back to 2014-15, when China, Brazil, and Peru signed an agreement to explore the construction of a “Two-Ocean Railway”. This railway would potentially connect Brazil’s Atlantic coast to Peru’s Pacific coast, creating a transcontinental link.

Its very origins may go back to South American regional cooperation of the 1960s, but it has remained on the drawing board due to the prohibitive cost of construction through the difficult terrains of the Andes and tropical forest.

The idea was fully revived in 2024-25 when the Brazilian government allocated US$17 billion to building and upgrading the national railway system from east to west, as an integral part of the “South American Integration Plan” championed by President Lula da Silva. This initiative was marked by an official delegation from China’s Ministry of Transportation and State Railway Co. visiting Brazil to discuss the construction of the Two-Ocean Railway.

They highlight a continuity in the BRI’s emphasis on large-scale infrastructure projects as the initiative enters its second decade, even as an alternative official narrative unfolds.

Once reaching the Port of Chancay in Peru, which was built by China and inaugurated in November 2024, this railway will allow Brazil to significantly reduce shipping times to Shanghai. The journey will be shortened from 35-40 days to just 23 days, while also cutting costs by over 20% compared to the northern route through the Panama Canal.

In collaboration with Brazil’s “going east” strategy, the Peruvian government has initiated its own railway plan, promoting it in China with an estimated total construction cost of US$31 billion. Although the eventual financing structure for such an expensive project remains unclear, the realisation of rail-sea intermodal shipping between Brazil and Peru would be transformative for both economies and for South American integration. The progress of this railway underscores the return of large-scale rail projects on the BRI agenda.

BRI’s emphasis on large-scale infrastructure projects

Relative to the “small and beautiful” motto of the new BRI, the new cross-border projects smack of “big and build”. However, unlike earlier rail projects, they do not involve China providing primary or bulk financing. Nor are they promoted as flagship projects of the BRI’s first decade.

Nevertheless, these rail projects hold significant geoeconomic importance for China and its partners, comparable to the earlier railways. They highlight a continuity in the BRI’s emphasis on large-scale infrastructure projects as the initiative enters its second decade, even as an alternative official narrative unfolds.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)