China’s surging auto sales mask an industry in crisis

While 2025 is shaping up to be another stellar year for China’s auto industry on paper, what do factories, dealerships and corporate boardrooms really show about the state of the industry?

(By Caixin journalists Yu Cong, Ding Shaohui and Kelsey Cheng)

On paper, 2025 is shaping up to be another stellar year for China’s auto industry.

In the first six months of 2025, automakers in China produced 15.62 million vehicles and sold 15.65 million, with both figures jumping more than 10% year-on-year, according to figures released by the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers (CAAM) earlier this month.

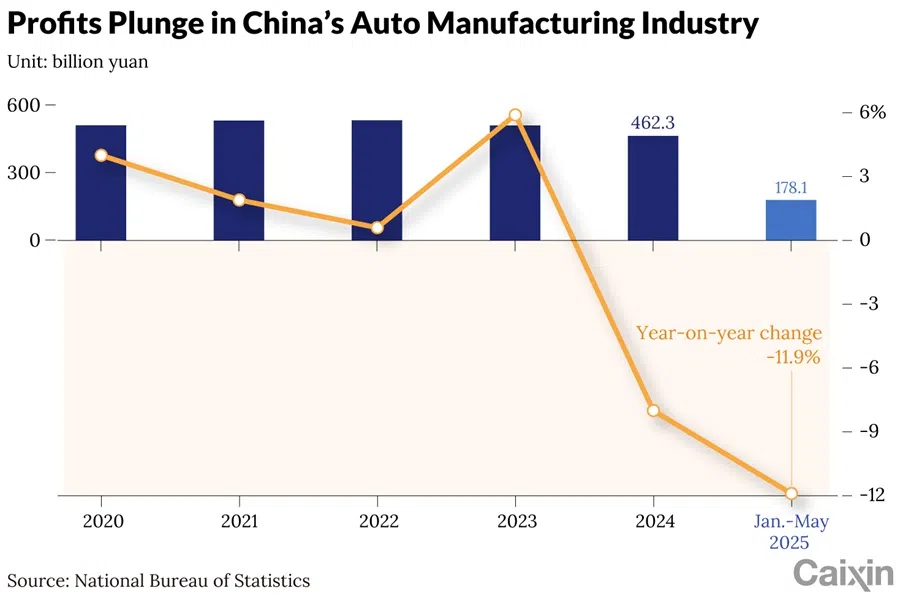

But in factory floors, dealerships and corporate boardrooms across the country, the mood is far from celebratory. While consumers are snapping up ever-cheaper cars, the companies that build them are suffering. Auto manufacturers’ total profits fell 12% to 178 billion RMB (US$24.8 billion) from January through May, data from the National Bureau of Statistics showed.

Over the past two and a half years, China’s auto industry has been gripped by a relentless price war amid a cycle of self-destructive hyper competition, termed “involution”. While price wars are a common feature of commercial competition, in China’s case, the price war has failed to achieve one of its supposed outcomes — accelerating industry consolidation. In fact, the market share of the 15 biggest automakers by sales shrank by 1.4 percentage points from a year earlier to 92.2%, according to CAAM.

The protracted battle not only threatens automakers’ profitability but also the vast network of suppliers and dealers, creating concerns over the long-term health of the world’s largest auto market.

“In many cases, carmakers didn’t have to pay a cent to build new production capacity,” said a person familiar with China’s auto policy planning.

Beijing is stepping in with a renewed sense of urgency. Since February, policymakers and regulators have accelerated a push for industry-wide consolidation to phase out excess capacity and underperforming brands.

In the long run, the solution lies not in suppressing market competition, industry insiders told Caixin, but in ensuring a smooth market exit mechanism for weaker players.

Setting the stage for ‘involution’

The current crisis was years in the making, fuelled by the rapid expansion of production capacity backed by government policy and the nation’s transition toward new energy vehicles (NEVs).

For over a decade, Beijing nurtured its nascent NEV industry with generous subsidies, creating a gold rush. Many local governments, eager for investment and jobs, offered lavish incentives to attract automakers.

“In many cases, carmakers didn’t have to pay a cent to build new production capacity,” said a person familiar with China’s auto policy planning. “Once production targets were agreed — say, an annual capacity of 200,000 units — the local government would fund the factory through its affiliated investment platforms.”

After years of rapid expansion, most automakers are now mired in overcapacity. By May 2022, China’s passenger car inventory had already surpassed 3 million units, and it has remained above that level since, hitting a five-year high of 3.45 million units in May 2025. With too many factories chasing too few buyers, a price war was almost inevitable.

Some local governments went even further, directing state capital to set up joint ventures or prop up underperforming companies, which has in some cases hampered the market’s ability to weed out the chaff and hindered consolidation.

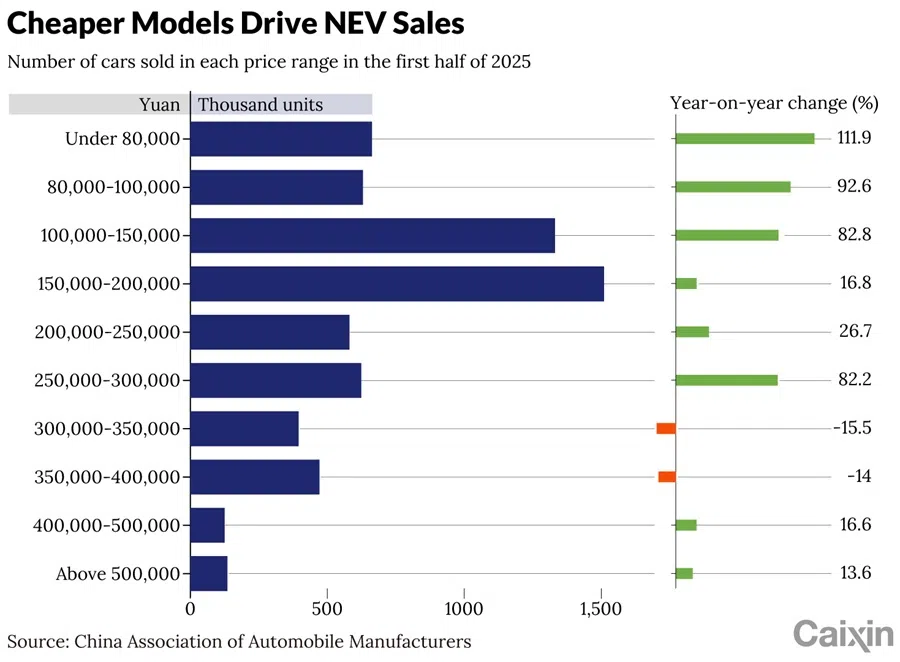

A lack of product diversity has compounded the problem. The shift from making complex internal combustion engines to simpler batteries and motors of NEVs lowered the barrier to entry. As a result, the market has become saturated with vehicles with little differentiation beyond their brand emblem.

“In the era of gasoline cars, consumers who valued durability and fuel efficiency bought Japanese cars; those who prioritised robust chassis and performance opted for German cars,” said an expert at the China Automotive Technology and Research Center Co. Ltd. “Now, with so many NEVs lacking distinct features, consumers just buy whichever is cheapest.”

The current state of China’s auto market is partly the result of an earlier government development mindset that encouraged firms to “go big and go fast”, pushing their production capacity to the limit, said a policy researcher at Dongfeng Motor Group Co. Ltd. “Now the blame is being placed squarely on the automakers,” he said.

A war that won’t end

The current price war began in January 2023, when Tesla Inc. made a bigger-than-expected round of price cuts in China to stimulate demand, dropping the price of its locally built Model Y SUV by 10% to 259,900 RMB and the Model 3 sedan by 14% to 229,900 RMB. With their market share threatened, Chinese automakers quickly slashed sticker prices of their own lines.

Contrary to expectations at the time, the price war showed no sign of easing. The average price reduction on discounted models was 22,000 RMB in 2023 and 18,000 RMB in 2024. In the first half of 2025, the average cut deepened to 21,000 RMB, according to data from the China Passenger Car Association (CPCA).

Electric vehicle (EV) giant BYD Co. Ltd. has emerged as both the most aggressive participant and the biggest winner. Since 2023, it has discounted one of its best-selling models by over 40%. The firm has held the top spot for passenger car sales in China for three consecutive years since 2022, cornering roughly 16% of the domestic market.

Across China’s auto market, per-vehicle profits have fallen from upward of 20,000 RMB before 2022 to 14,000 RMB in the first five months of this year, according to Cui Dongshu, secretary-general of the CPCA.

While BYD can afford to join the fray with its self-developed batteries and integrated supply chain, others do so reluctantly. “‘Price war’ is a term I dislike the most, because I was (forced) into it,” Chery Automobile Co. Ltd. Chairman Yin Tongyue said in May, as his company offered its own discounts. Li Shufu, chairman of Zhejiang Geely Holding Group Co. Ltd., warned last year that “endless involution and crude price wars” would lead to cutting corners and shoddy products.

As a result, many automakers, including established players, have faced unprecedented losses, such as Guangzhou Automobile Group Co. Ltd., which booked a 2.6 billion RMB net loss in the first half of 2025, down from a 1.5 billion RMB profit in the same period last year. Across China’s auto market, per-vehicle profits have fallen from upward of 20,000 RMB before 2022 to 14,000 RMB in the first five months of this year, according to Cui Dongshu, secretary-general of the CPCA.

Suffering spreads

Along the supply chain, suppliers and dealers are also feeling the pain of the price war, as automakers push for discounts and delay payments while oversupply clogs lots amid lax consumer demand.

A survey by consultancy AlixPartners of 253 domestic suppliers found that the share of auto parts suppliers reporting year-on-year profit growth had dropped from 61% in 2022 to 43% in 2024.

Several suppliers told Caixin that automakers now frequently demand aggressive annual price reductions, with some asking for quarterly discounts. One major automaker has adopted a “transparent bidding” system where suppliers’ offers are ranked publicly during tenders, fuelling a downward spiral in pricing, said one supplier of vehicle control systems.

Worse still are the payment terms. What was once a standard 45-day cash payment from foreign joint-venture automakers has morphed into a system that can leave suppliers waiting up to 270 days for their money. Many domestic brands now offer payment in 90 days, but with a 180-day bank or commercial acceptance draft.

“You can’t blame only the companies. After all, their primary goal is to make money. It’s the government’s job to regulate.” — Veteran insider

Dealers are faring no better, with inventory backlogs rising and cash flow tight. Nearly 73% of dealerships failed to meet their sales targets in the first half of the year while some 42% reported losses in 2024, according to the China Automobile Dealers Association.

In June, dealer associations across Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Anhui and Shanghai sent a joint letter to major automakers warning of mounting inventory and serious financial distress, calling for urgent support. Similar pleas have since been made in Guangdong, Sichuan and Henan.

There are also growing concerns that extreme cost-cutting mentality could eventually compromise product quality and safety. One veteran industry insider said that prolonged race-to-the-bottom tactics are likely to force suppliers into adopting unconventional, even risky, practices.

Government intervenes

Faced with an industry accelerating out of control, the government is intervening fast.

On 16 July, Premier Li Qiang chaired a State Council meeting that called for “stronger regulation of market order” and set up cost and price monitoring mechanisms in the NEV sector “to curb irrational competition”. This followed condemnations of “involution-style competition” from the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) in May.

One issue is a lack of comprehensive regulation, which leaves “grey areas”, while another is that certain “reckless practices” have spread across the industry unchecked, the veteran insider said. “You can’t blame only the companies. After all, their primary goal is to make money. It’s the government’s job to regulate.”

The government’s new playbook has several components. First is a crackdown on the exploitation of suppliers. A revised regulation that took effect on 1 June mandates automakers pay small and midsize suppliers within 60 days. In a sign of enforcement, major automakers, including state-owned giants China FAW Group Co. Ltd. and SAIC Motor Corp. Ltd., publicly pledged to adhere to the term. The MIIT followed in July with the launch of a dedicated online portal for suppliers to report violations.

Second is tougher legal backing. A revised Anti-Unfair Competition Law, set to take effect on 15 October, specifically prohibits large firms from using their market power to force unfair payment terms on smaller suppliers. Violations could be punished with fines of up to 5 million RMB.

Third is a renewed push for consolidation. The National Development and Reform Commission, the country’s top economic planner, said in March that regulators would seize the opportunity presented by the auto industry’s transformation to support healthy players, eliminate laggards, and advance the reform of managing automakers. Regulators will also clear out outdated production capacity through market-based and law-based mechanisms.

Of the 129 brands selling NEVs in China in 2024, only 15 will be financially viable by 2030, AlixPartners projected in a report in early July.

The end game

Ending involution doesn’t mean rejecting all competition. The consensus among industry leaders is that a painful shakeout is both necessary and inevitable to end the chaos.

Of the 129 brands selling NEVs in China in 2024, only 15 will be financially viable by 2030, AlixPartners projected in a report in early July.

Large-scale mergers remain difficult. The auto sector’s long value chain means that carmakers are deeply entwined with regional economies and labour employment. A months-long plan to merge Dongfeng Motor and Chongqing Changan Automobile Co. Ltd. fell through earlier this year, dealing a blow to Beijing’s broader plan to consolidate its state-owned automakers.

However, consolidation is beginning within corporate families. Geely Automobile is moving to fully acquire and merge with its premium EV subsidiary Zeekr. Geely Automobile CEO Gui Shengyue said in mid-May that given fierce market competition and a complex economic backdrop, the company needed to move beyond its “small, scattered and disorganised” brand structure.

GAC Group is also integrating its Aion and Trumpchi brands to share research and development (R&D) and procurement costs.

To break out of price involution, automakers must increase investment in R&D and outperform competitors in key technologies to create differentiated products, said former MIIT Minister Miao Wei in late March. Li Auto Inc. pulled this off with an early bet on extended-range hybrids, which helped it become the first among China’s major EV upstarts to turn an annual profit in 2023.

This article was first published by Caixin Global as “In Depth: China’s Surging Auto Sales Mask an Industry in Crisis”. Caixin Global is one of the most respected sources for macroeconomic, financial and business news and information about China.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)