Power plays: China’s hydropower diplomacy in Latin America

As hydropower remains the dominant source of electricity in most Latin American countries, China is well-positioned to use that as a pivot for greater economic engagement with the region. Singapore-based Indian researcher Amit Ranjan and Australian researcher Genevieve Donnellon-May explore the issue.

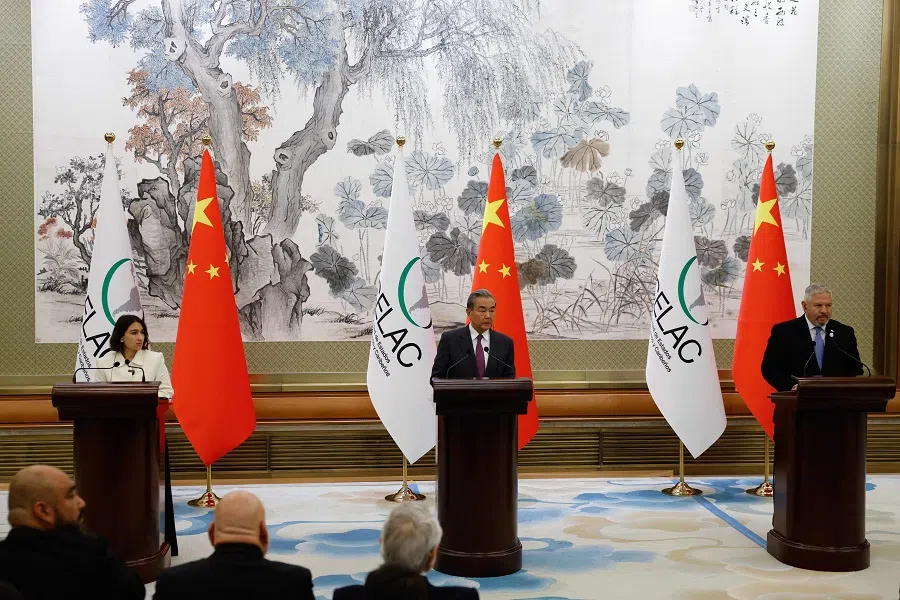

As the geopolitical chessboard shifts, China is moving its Latin American strategy into high gear. The most recent China–CELAC (Community of Latin American and Caribbean States) Forum Ministerial Meeting, held on 13 May in Beijing, took place amid ongoing US–China trade tensions, which seems to have eased following recent talks in Geneva, where both sides committed to “mutual opening, continued communication, cooperation, and mutual respect”.

The forum highlights China’s deepening economic and diplomatic ties with Latin America — a region traditionally within Washington’s sphere of influence — underscoring Beijing’s broader push for a more multipolar world.

Estimates suggest that around two-thirds of CELAC countries are now members of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

New agreements and growing ties

Twenty-eight Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) countries, six regional organisations, and over 50 ministerial-level officials convened in China for the triennial China-CELAC Forum. Established in 2015 as a multilateral cooperation mechanism, the inaugural ministerial meeting of the China-CELAC Forum took place in Beijing on 8-9 January 2015. The meeting adopted three important outcome documents, including the Beijing Declaration, the five-year cooperation plan and the operational rules for the forum.

In 2025, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced a financial package worth around US$9.18 billion, aimed at boosting credit and infrastructure investment in CELAC member states. Although smaller than the US$20 billion offered in 2015 in credit to be used to help Chinese enterprises invest in infrastructure projects, this year’s package reflects a more targeted and RMB-denominated investment strategy.

Xi also announced that visa-free travel would be rolled out for citizens from five countries — Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Peru and Uruguay. For a trial, effective for one year, from 1 June, citizens from the five countries will be allowed to enter China for up to 30 days without a visa.

The forum produced the China-CELAC Joint Action Plan for Cooperation in Key Areas (2025–2027), alongside more than 100 three-year cooperation projects. The overarching message was clear: China and Latin America are “important members of the global south” with shared values of independence, development and justice.

Trade between China and Latin America has exploded over the past two decades. Estimates suggest that around two-thirds of CELAC countries are now members of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Bilateral trade between China and CELAC reached US$515 billion in 2024, up from US$450 billion in 2023 and a mere US$12 billion in 2000.

Within the BRI, these investments reflect China’s ambition to shape the region’s energy architecture while securing geostrategic and commercial footholds.

China’s BRI investment in the hydropower sector

China’s expanding footprint in Latin America closely parallels its dam-building diplomacy and broader “south-south cooperation” strategies across Asia and Africa. Within the BRI, these investments reflect China’s ambition to shape the region’s energy architecture while securing geostrategic and commercial footholds.

Hydropower remains the dominant source of electricity in most Latin American countries, accounting for around 45% of the region’s total electricity supply according to the International Energy Agency. With additional projects in the pipeline, this dependence is poised to grow.

Estimates suggest that between 2000 and 2023, the China Development Bank and China Export-Import Bank have financed around US$10 billion in energy generation and distribution projects across Latin America and the Caribbean. In Latin America, countries such as Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador and Peru have emerged as key destinations for Chinese hydropower investments. Likewise, in Honduras, China has been involved in the Patuca II-A, II-B, and III hydro projects on the Patuca River — the country’s largest.

In 2020, China Yangtze Power, a subsidiary of China Three Gorges, acquired Luz del Sur — a Peruvian company responsible for delivering electricity to the south of Lima and beyond. The deal additionally stated that the Chinese company would acquire interests in Inland Energy, which was involved in the Santa Teresa I dam and in the construction of the Santa Teresa II, Llulla and Lluta power generation plants. It also has stakes in Peru’s Chaglla and San Gaban III dams.

Further linking overseas Chinese investment to energy generation, China State Grid made a major move in Chile by acquiring 97.3% of Compañía General de Electricidad (CGE) for US$3 billion in 2020. CGE transmits and distributes electricity across 11 of Chile’s 16 regions. Doing so reinforces China’s growing role not only in energy generation but also in transmission and distribution infrastructures.

In Brazil, also, Chinese firms have acquired stakes in 304 power plants, amounting to 10% of the country’s national energy generation capacity. In 2015, China Three Gorges paid the Brazilian Government US$3.7 billion for the right to run two hydropower plants — Jupiá and Ilha Solteira dams — with a combined capacity totalling 5,000 megawatts, in a 30-year operating contract.

Some of the China-backed hydropower projects have faced resistance and sparked concerns. These range from transparency and governance to environmental degradation and labour rights violations.

Governance and environmental concerns

Despite their contributions to energy infrastructure, some of the China-backed hydropower projects have faced resistance and sparked concerns. These range from transparency and governance to environmental degradation and labour rights violations.

Public resistance to dam-building is strong in many Latin American countries, with particular unease surrounding a few Chinese-financed projects. In 2012, Ecuadorian workers at Sinohydro’s US$2.2 billion Coca Codo Sinclair dam project reported unpaid wages, abuse, and sexual harassment. While the company denied all such allegations, the incident sparked scrutiny over labour practices.

In Chile, the US$240 million Rucalhue project on the Biobío River — run by Rucalhue Energía, a Chilean company owned by China International Water and Electric (a subsidiary of the China Three Gorges Corporation) — has faced resistance from local communities mainly over ecological damage. The Biobío Basin, home to 13 hydropower plants, supplies 38% of Chile’s hydroelectric power and remains a hotspot for environmental activism.

Elsewhere, in Brazil, tensions arose when a Chinese firm planned to bring in 11,000 Chinese workers to build a 2,100-km power line from the Belo Monte hydroelectric plant, in violation of Brazilian labour laws, which forbid companies from hiring foreign workers. In Bolivia, also, a PowerChina subsidiary involved in six infrastructure and energy projects has faced complaints of deforestation, labour disputes, and substandard work.

Can China and Latin America build together responsibly?

With trade, investment in infrastructure, and soft power overtures intensifying, China has become a significant player in the region. Beijing’s involvement in Latin America’s hydropower sector reflects both strategic ambition and practical investment. The Chinese-backed projects address real infrastructure needs. However, on the other hand, concerns about transparency, environmental harm, labour violations and governance persist.

As China cements its role as a key player in the region’s energy landscape, Latin American governments have to weigh the benefits of development against the long-term social and environmental costs. In such a situation, whether this relationship fosters mutual growth will depend not only on China’s plans for the region but also on how Latin American states and societies respond to Beijing’s call.