The real winner of the tariff war

As the US seeks a “total reset” of China-US trade relations, China is at the critical juncture of industrial upgrading and economic transformation, with the success of its modernisation hanging in the balance, says academic Jianyong Yue.

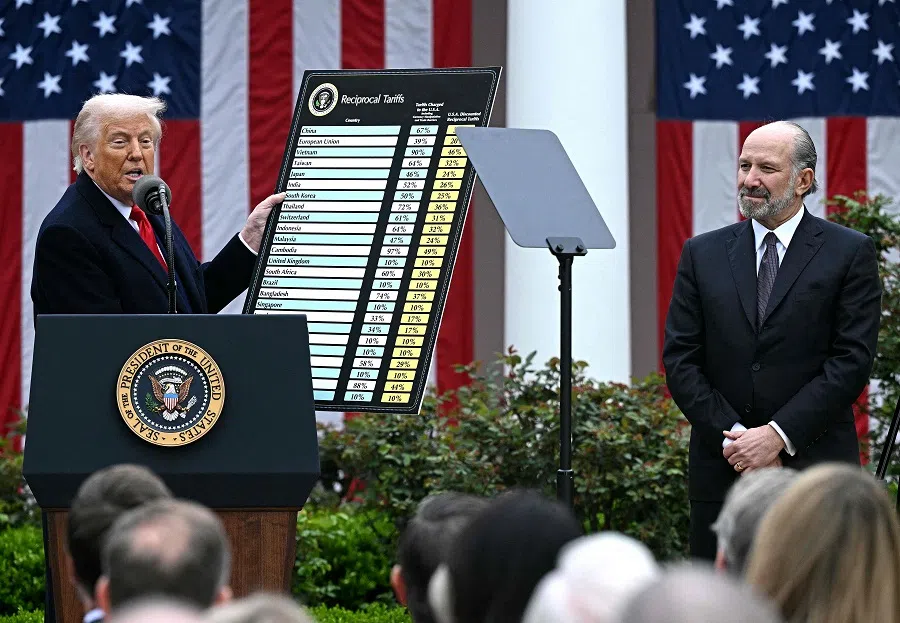

With the US and China clashing over tariff policies, the escalating trade war has drawn significant global attention. The two parties held emergency talks in Geneva from 10-11 May, and quickly reached a consensus to pause the tariff war for 90 days. According to the agreement, the US will sharply reduce its baseline tariffs from 145% to 30%, while China will lower its tariffs from 125% to 10%.

Global public opinion generally thinks that China gained the upper hand in this round of negotiations. The Economist claimed that US President Donald Trump gave Beijing a “strangely good tariff deal”; The New York Times criticised the effectiveness of the US tariff strategy, which not only failed to force China to make substantial concessions but instead left American businesses in distress; while The Guardian even called 12 May Trump’s “Capitulation Day”.

The actual tariff differential between the US and China is not 30% versus 10%, but rather closer to 50% versus 10%, posing a significant challenge for China’s future exports.

The true winner

However, the fact sheet that the White House subsequently published revealed a different reality: the apparent reduction of tariffs to 30% does not include those imposed on China prior to 2 April, including Section 301 tariffs, Section 232 tariffs, fentanyl-related tariffs and Most Favoured Nation tariffs. In other words, the actual tariff differential between the US and China is not 30% versus 10%, but rather closer to 50% versus 10%, posing a significant challenge for China’s future exports.

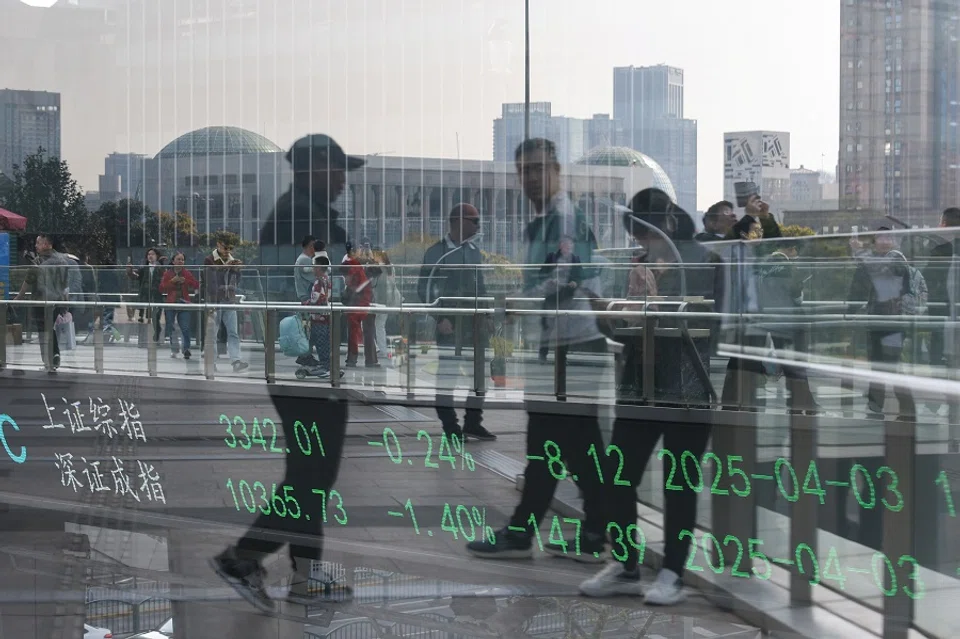

Prior to “Liberation Day” on 2 April, the tariff differential between the US and China was only 20% versus 15%. Chinese export enterprises mitigated the impact of tariff barriers by improving internal efficiencies and rerouting goods through third countries. Despite a 21% drop in shipments to the US in April, China’s overall exports defied the trend and grew 8.1%.

In the first four months of the year, Chinese exports to ASEAN countries and Latin America both jumped 11.5%. Shipments to India grew nearly 16% by value, and exports to Africa surged 15%. Exports to Vietnam and Thailand were even up 18% and 20% respectively. The diversification of supply chains is accelerating, and the trend of “rerouted exports” is becoming increasingly apparent.

China courts neighbours while the US tightens its grip

Faced with China’s flexible and adaptive strategies, the US is forced to adopt more stringent measures to curb China’s export advantages, mainly focusing on the strict enforcement of “rules of origin” and exerting pressure on transhipment countries, forcing them to choose between aligning with China, and maintaining access to the US market. The competition between China and the US over these neighbouring countries, given their geopolitical strategic value, is intensifying.

On 8-9 April, the Chinese Communist Party convened the Central Conference on Work Related to Neighbouring Countries and proposed the strategic concept of building a “community with a shared future with neighbouring countries”. The Chinese government then swiftly launched a charm offensive in its diplomatic efforts to win over neighbouring countries.

In particular, Vietnam has emerged as the primary focus of China-US rivalry. On 15 April, Vietnam and China signed 45 cooperation agreements. Yet, that same day, Vietnam issued a strict directive to crack down on illegal transhipment of goods to the US. Subsequently, Vietnam strengthened its comprehensive strategic partnership with the US, making substantial progress in defence, such as the procurement of F-16 fighter jets and C-130 transport aircraft.

Despite China’s proactive attempts to win over neighbouring countries, most of them are reluctant to take retaliatory measures against the US, instead choosing to negotiate with the US to lower tariffs in exchange for relaxed sanctions. This reality highlights the significant challenges China faces in persuading neighbouring countries to choose sides.

Trump’s ‘total reset’

This situation has pushed Chinese export enterprises to the brink of survival. Starting on 2 April, US tariffs on Chinese goods surged to 54%, prompting swift retaliation from China. In response, the US escalated the situation further, imposing tariffs as high as 145% by April 11 — levels approaching a de facto embargo.

However, the US does not intend to completely sever trade ties with China; its real aim is to advance strategic decoupling, particularly in the high-tech sector, rather than a complete decoupling. Its interest in China’s massive market has never weakened.

To him, trade deficits equate to economic aggression, and with China being the largest source of these deficits, it naturally became the primary adversary.

It is precisely against this backdrop that Trump hailed a “total reset” in China-US trade relations, aimed at forcing China to accept a larger tariff differential, thereby reducing the US’s trade deficit and pushing bilateral trade towards a more balanced state.

Since his first presidency in 2017, Trump has quickly placed trade issues at the core of US diplomacy and was the first to explicitly link economic security with national security. He argued that long-term trade deficits erode the manufacturing sector, destroy jobs, and ultimately weaken the foundations of US economy and defence, posing a significant threat to national security. To him, trade deficits equate to economic aggression, and with China being the largest source of these deficits, it naturally became the primary adversary.

As China-US decoupling intensified, the volume of bilateral trade plummeted. Although China’s trade surplus with the US had been declining annually amid a high tariff pressure of 20%, China still achieved a surplus of US$295.4 billion in 2024. For a president with a mere four-year term, this outcome was unacceptable — Trump therefore felt compelled to adopt more extreme measures to curb the trade deficit, otherwise his promise to “make America great again” would be challenged.

Trump already had the upper hand

Faced with a China that “won’t kneel down”, Trump’s inconsistency is unsurprising. The US has traditionally prioritised practical benefits over appearances, and Trump, being a businessman, is even less concerned with formalities. By raising tariffs to nearly absurd embargo levels, he in fact aims to create significant psychological pressure and gain an advantage in negotiations.

Also, the upcoming formal negotiations will not only solidify the outcomes of the phase one trade deal signed in January 2020, but could also advance phase two negotiations.

More importantly, Trump already had the upper hand when initiating these talks: on the one hand, he had achieved a critical breakthrough in the peripheral tariff wars targeting transhipment countries, leaving China isolated; on the other hand, China’s weak domestic demand and lacklustre domestic economic circulation made it reliant on external demand for economic support. Trump confidently declared that China is “getting absolutely hammered” by the tariff war and was convinced that China would ultimately succumb to US pressure and return to the negotiating table.

During the current round of negotiations, Trump successfully forced China to accept a “tariff differential” arrangement highly advantageous to the US. Furthermore, in the following 90-day reprieve, the US holds almost all the cards: if the trade deficit does not narrow as expected, the US side can restore the high tariffs at any time.

Also, the upcoming formal negotiations will not only solidify the outcomes of the phase one trade deal signed in January 2020, but could also advance phase two negotiations. Industrial subsidies will become a core issue, in an attempt to coerce China to complete structural adjustments.

During this observation period, any trade outcome that falls short of US expectations can be used as bargaining chips in a new round of pressure on China, demanding further market opening and even the abandonment of key industrial policies.

Trump’s grand strategy: reversing the ‘colonial relationship’

Many commentators believe that Trump does not want a hot war with China, but instead intends to force his opponent to yield through economic warfare, achieving a bloodless victory. This assessment is not unfounded.

Trump’s trade protectionism is neither isolationist nor truly deglobalising. Instead, it is a strategic gambit waged under the banner of “fair trade”, but in reality aimed at forcibly restructuring the global division of labour. Its fundamental goal is to revitalise American manufacturing and rebuild the country’s industrial and defence base by brandishing tariffs as a weapon.

This is intended to reverse a trend deeply worrying to the “America First” camp (exemplified by former trade representative Robert Lighthizer): that the US is falling into an asymmetrical and dangerous “colonial relationship” with powerful rivals like China.

Thus, Trump’s apparent shift from hostility to conciliation in the tariff war is more likely a negotiation tactic than a wavering of his stance. He remains calm and resolute in his pursuit of national interests. In terms of practical results, the Trump administration has achieved its initial objectives in key areas: reducing the China-US trade imbalance through an expanded tariff differential, thereby creating breathing room for American industries.

The “total reset” is not only a reconstruction of tariff structures, but a coercive project to force China to further open its markets. For example, after the Geneva negotiations, China relaxed export controls on some rare earths and allowed US investment into previously closed key sectors. But at the same time, the US has not made any substantial concessions regarding export controls on advanced technologies, and even strengthened its technological blockade against China, maintaining a firm grip on strategic high ground.

If China does not decisively initiate political reforms, and force the powerful elite to concede benefits to the people and establish a fairer, more transparent and efficient public resource allocation mechanism, it would be difficult to truly unleash its vast domestic demand potential...

This “all take, no give” policy approach is a true reflection of Trump’s aim to reshape trade relations — he seeks not balanced reciprocity, but structural dominance.

China: to rely on itself or others?

For China, the Geneva talks are but a temporary reprieve from the crisis, not the resolution of it. The US’s correction of global imbalances is but a matter of time, and the firm determination and aggressive tactics it displayed this time indicate that “global imbalances” are now an unavoidable core challenge. This has again punctured the “globalisation myth” — China’s development model, reliant on rising through globalisation, will eventually hit its “growth limit”. Just as Singapore’s founding father Lee Kuan Yew had predicted in 1992, a large country like China must ultimately rely on domestic demand for sustainable development.

In fact, China had proposed to expand domestic demand as early as 1998. However, progress over the past two decades has been limited. The problem lies not in a lack of tools, but in a persistent avoidance of the systemic root of insufficient inelastic domestic demand.

If China does not decisively initiate political reforms, and force the powerful elite to concede benefits to the people and establish a fairer, more transparent and efficient public resource allocation mechanism, it would be difficult to truly unleash its vast domestic demand potential, and a self-reliant internal circulation will merely remain on paper.

Consequently, China will have to continue relying on external demand, especially on the US as its largest market, thus remaining strategically passive and subject to the influence of others in its development strategy.

Presently, China is at the critical juncture of industrial upgrading and economic transformation, with the success of its modernisation hanging in the balance. Meanwhile, the Trump administration is employing a combination of high tariffs and industrial policies (described by Lighthizer as a “blend of Hamiltonianism and Jeffersonianism”) to vigorously promote the US’s reindustrialisation. Simultaneously, the US is continuously squeezing China’s industrial policy space and challenging its economic sovereignty.

China must remain highly vigilant: if it cannot resolutely advance a political and economic reform that would truly benefit most citizens, it risks becoming increasingly trapped in a passive position in economic diplomacy.

The real aim of Trump’s “total reset” in China-US trade relations is just as Michael Pillsbury has revealed: transforming all of China into a Shanghai Free-Trade Zone, essentially turning it into a fully comprador economy.

China must remain highly vigilant: if it cannot resolutely advance a political and economic reform that would truly benefit most citizens, it risks becoming increasingly trapped in a passive position in economic diplomacy. Ultimately, it may be forced to sacrifice its developmental rights and policy autonomy in exchange for short-term stability in external markets.

The cost of such strategic concessions will not only squander China’s historic opportunity to surpass developed countries but could also push the nation towards the path of “Latin Americanisation”, trapping it in a real “colonial relationship” as a vassal of a US-led global capitalist economic system.

Only by confronting these challenges head-on, abandoning pride and arrogance, and steadfastly pursuing a people-centred development path can China truly achieve the historic leap from “dependent development” to “autonomous development”. China can then stand tall and remain invincible amid global competition, forging a new path towards modernisation that is characterised by strategic resolve, institutional resilience, with a foundation rooted in the people.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “关税刀锋:中美博弈谁主沉浮?”.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)