The rise of China’s ‘affordable MUJIs’ and what it means for the original

China’s homegrown brands like Miniso and NetEase Yanxuan are rapidly gaining ground with affordable, stylish products that challenge MUJI’s dominance. As these “affordable MUJIs” grow, the original brand is forced to rethink its strategy in a shifting market. Lianhe Zaobao’s China Desk takes a look at MUJI’s strategy to expand in China.

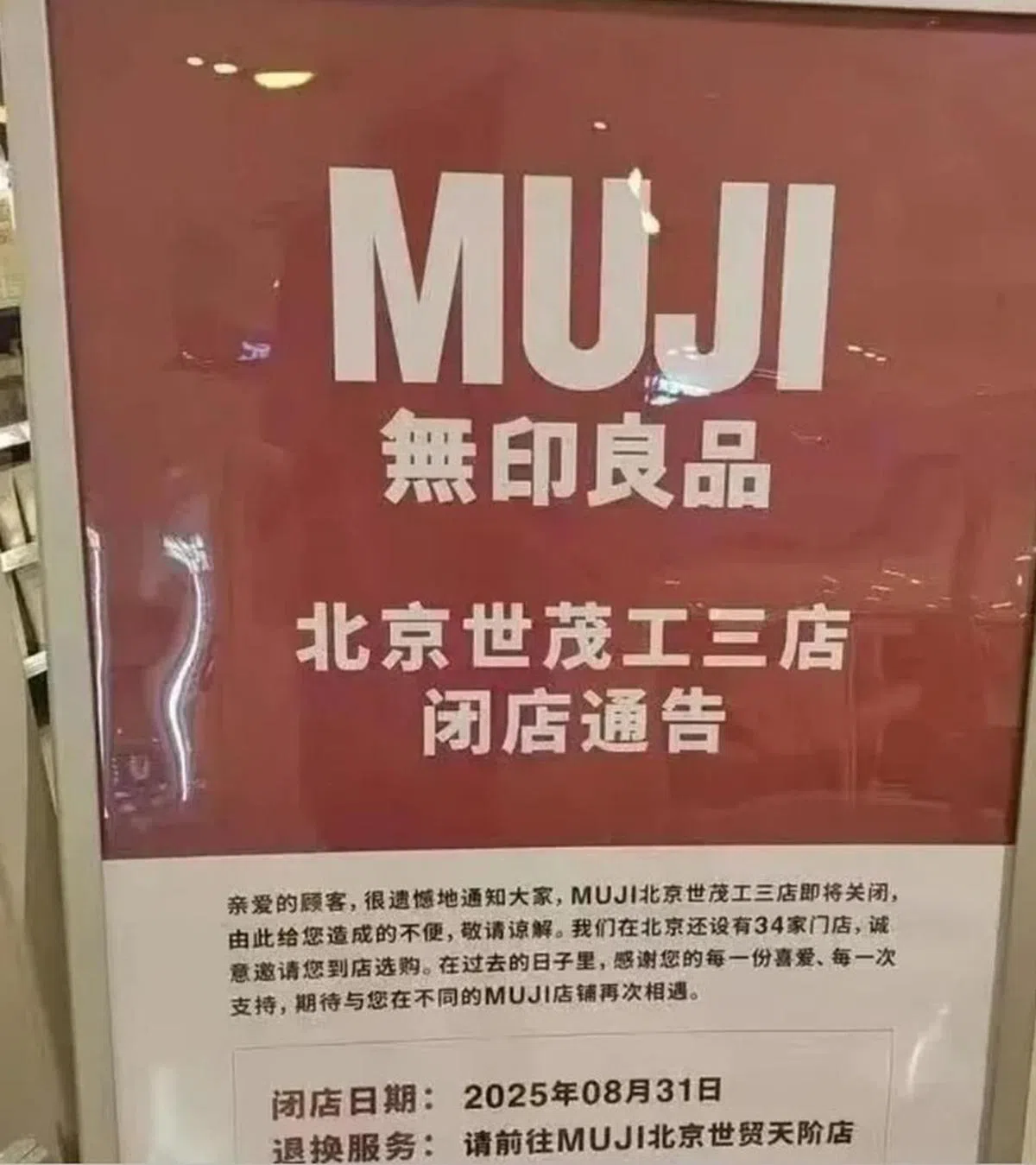

The recent shuttering of several MUJI (无印良品) stores across China has drawn much attention. Known as the “beloved brand of the middle class” in China, has MUJI lost its Midas touch?

Beyond Beijing, MUJI has also closed locations in Shanghai, Zhejiang, Jinan, Wuhan and Changsha since the beginning of the year.

Social media users shared a photo of a closure notice at MUJI’s Shimao Gongsan store in Beijing, which officially shut down on 31 August. The notice read: “34 MUJI stores remain in the city — we warmly invite you to visit them.” According to Chinese media, the closure followed the recent opening of a nearby MUJI store in Sanlitun.

Beyond Beijing, MUJI has also closed locations in Shanghai, Zhejiang, Jinan, Wuhan and Changsha since the beginning of the year. Notably, an 11-year-old store in Jinan’s Shizhong district and the Bofu International Plaza branch in Changsha both shut down at the end of August.

MUJI said the closures are routine adjustments to improve efficiency, citing declining foot traffic in some areas. Despite this, MUJI China still targets 40 new store openings annually and has opened 15 since 1 March 2025.

Once beloved brand of China’s middle class

MUJI, a Japanese brand founded in 1980, started with the goal of offering simple, affordable products. Its name literally means “no-brand quality goods”.

In 2005, MUJI officially entered the mainland Chinese market with its first store on Nanjing West Road in Shanghai. At the time, China’s economy was rapidly developing, with consumption upgrading and the middle class on the rise. MUJI’s minimalist style resonated with the aesthetic preferences of China’s burgeoning urban middle class, drawing in a large number of loyal followers.

“Simple aesthetics”, “normcore style”, and “rational and restrained” became fashionable labels pursued by the middle class as well as young artistic individuals.

Strong consumer enthusiasm fuelled MUJI’s rapid growth in China, making it the company’s biggest market outside Japan.

On Chinese social media platform RedNote, a netizen lamented about MUJI’s pricing, “Am I too poor or are you too expensive?”

By the end of 2019, MUJI had 256 stores in China, accounting for more than half of its global store count. As of August 2024, there were over 400 stores in China.

Pricing and quality controversies

Over its two decades in China, MUJI has faced several controversies, with pricing being the hot issue.

Some consumers feel that MUJI’s pricing is too high, especially since it is positioned as a “general store” in Japan — yet when it expanded to China, it became a “boutique store” for mid- to high-end consumers.

Comparing the prices of products in the same category, netizens found that the prices in China were almost double those in Japan. On Chinese social media platform RedNote, a netizen lamented about MUJI’s pricing, “Am I too poor or are you too expensive?”

MUJI regards feedback from the massive Chinese market seriously. Since 2014, the brand has made more than a dozen price reductions.

In 2019, MUJI even announced on social media its commitment to “continue reviewing prices and make changes for China”, with the prices of some products reduced by almost 50%.

In an interview in November 2023, MUJI China’s chairman and general manager Shimizu Satoshi stated that the price difference between their products in China and Japan was now minimal — “almost non-existent”. He added that the company has done its best, but if high prices remain a concern, they will take the feedback seriously and keep working to meet customer expectations.

Apart from pricing, MUJI also faced multiple quality controversies. Netizens have complained about quality control issues, including loose threads on T-shirts after a day or two of wear, clothes pilling and solid wood tables cracking.

In May this year, MUJI (Shanghai) Commercial Co. was fined over 30,000 RMB (about US$4,178) for allegedly selling stainless steel scissors and ultrasonic aroma diffusers (humidifiers) that failed to meet safety standards, and for not properly labelling the manufacturer’s name and address on the scissors. Over the past two years, the company has been penalised four times for substandard products.

In Japan, MUJI is well regarded for its high quality at reasonable prices. However, according to a Nikkei MJ consumer survey in China, only 17% of respondents saw MUJI as a high value-for-money brand.

Rise of Chinese domestic brands

MUJI’s rise in the Chinese market coincided with China’s economic boom and a wave of consumer upgrading. But over the past two decades, the country has undergone profound changes in its economic landscape, business environment and consumer confidence.

Especially after the pandemic, China’s economic recovery has been sluggish, and consumers have become more cautious and conservative — making MUJI’s pricing strategy stick out like a sore thumb.

In Japan, MUJI is well regarded for its high quality at reasonable prices. However, according to a Nikkei MJ consumer survey in China, only 17% of respondents saw MUJI as a high value-for-money brand.

Also, with China’s rapid industrial development, a wave of local brands has emerged, offering affordable alternatives that rival MUJI in both design and quality.

These domestic brands — more affordable and of similar style — have undoubtedly chipped away at MUJI’s market share in China.

Founded in 2013, Miniso was initially nicknamed “knockoff MUJI” or “budget MUJI” for its similar aesthetics. However, as the brand rapidly expanded, Miniso secured a strong foothold in the fast-moving consumer goods market.

NetEase Yanxuan, which partners with major manufacturers, was launched in 2016 and instantly dubbed the “affordable MUJI”.

In 2017, Xiaomi Youpin was established, offering minimalist lifestyle products backed by Xiaomi’s ecosystem and applying its business model to consumer goods.

That same year, Taobao Xinxuan was introduced, emphasising affordability and simplicity. Within a year, it featured over 2,000 stock-keeping units and over 800 standardised products, drawing over 100 million visits.

These domestic brands — more affordable and of similar style — have undoubtedly chipped away at MUJI’s market share in China.

Closing stores while opening new ones

Despite fierce competition and a constantly changing market, MUJI’s performance in China remains strong. In the first nine months of fiscal 2025, MUJI’s parent company reported a 19.2% year-on-year revenue increase to 591.09 billion yen (US$3.97 billion), while its operating profit surged 39.9% to 59.4 billion yen. The company’s net profit attributable to shareholders increased by 30.1% to 43.59 billion yen.

Mainland China has performed outstandingly, with both brick-and-mortar stores and e-commerce channels seeing continuous growth for ten consecutive months — up 117.3% year-on-year in total.

This year alone, the brand closed 22 stores but opened 62 new ones, including major flagships such as the one in Beijing’s Chaoyang Joy City.

Notably, while MUJI has been closing underperforming stores, it is also opening larger flagship stores.

This year alone, the brand closed 22 stores but opened 62 new ones, including major flagships such as the one in Beijing’s Chaoyang Joy City. When the Changsha’s Bofu International Plaza store shut down, MUJI announced that it will be opening its largest location in central China at Livat Changsha, where it would occupy a two-storey space spanning over 2,000 square metres.

Amid economic downturns and growing uncertainty in consumer spending, MUJI has begun targeting sinking markets in China’s smaller cities.

Nikkei reported that starting this summer, Muji will open small stores (under “Muji 500”) specialising in daily necessities and consumable goods in China, with around 70% of items being priced at 500 yen or less. These will be MUJI’s first such stores located overseas.

Some of MUJI’s existing low-priced product lines such as affordable beauty items and hemp clothing have also become new growth drivers, offering competitive pricing even against domestic Chinese brands.

Objectively, MUJI’s wave of store closures does not signal a full retreat from China, but rather a strategic adjustment in response to shifting market dynamics.

But behind these adjustments lies a deeper transformation in China’s consumer landscape. Once a favourite among the middle class, MUJI now finds itself needing to recalibrate, reassessing its market positioning and value proposition.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “无印良品,中产带不动了?”.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)