Made in China or spent in China? Beijing’s impossible balancing act

As growth slows and trade tensions persist, China faces a hard choice: double down on manufacturing dominance or transform into a consumption-driven economy. It cannot be both, says Indian researcher Amit Kumar.

In his address to the World Economic Forum’s 16th Annual Meeting of the New Champions in Tianjin, Chinese Premier Li Qiang expressed his vision of China becoming “a mega-sized consumption powerhouse”. He said, “China is the world’s second largest consumer market and importer, with nearly RMB50 trillion yuan of consumption.” He continued, “We are intensifying our efforts to implement the strategy of expanding domestic demand by launching special initiatives to boost consumption. This will make China a mega-sized consumption powerhouse on top of being a manufacturing powerhouse.”

Incidentally, a Financial Times piece from a week ago argued that the notion that China “consumes too little and invests too much” is “the great half-truth”. It further asserted that China’s “suppressed consumer is a myth”. The claim rested on one key data point — in this century, in real terms, private consumer spending in China has grown more than 8% a year, faster than in any other economy, by far.

It is true that private consumption in China has grown at a healthy pace, if one considers the long-term average of the last 25 years. China was the fastest-growing major economy in this century until India displaced it in 2015. And, until the pandemic hit, China was still growing at around 6% annually. No wonder, private consumption (one of the four components of GDP, along with private investment, government spending and net exports) also witnessed a healthy growth rate that outpaced other major emerging economies. There is no disagreement here.

But China’s underconsumption is neither a half-truth nor a myth. And Beijing surely needs to do a lot to become a mega-sized consumption powerhouse.

China’s private consumption on the decline

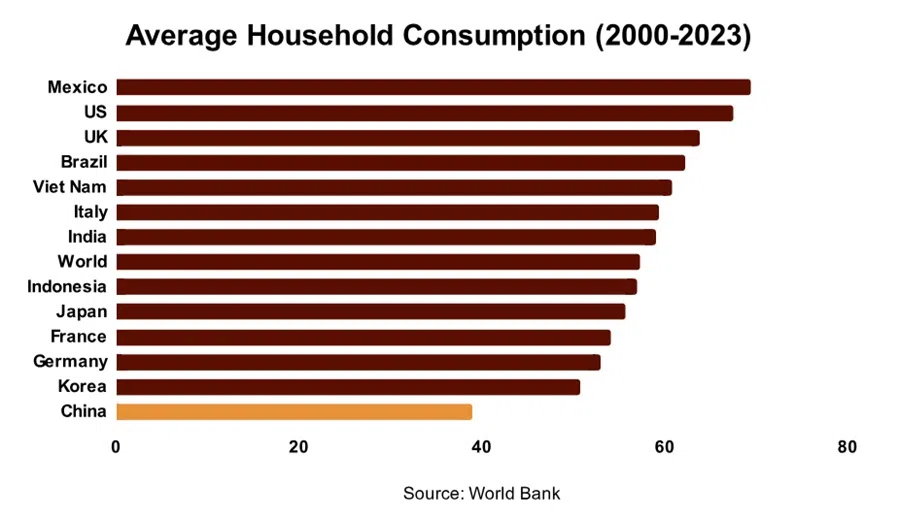

To begin with, the contribution of private consumption to China’s economy is abnormally low. In 2024, it accounted for a mere 40% of its GDP. The period between 2006 and 2022 was the worst, with the percentage contribution averaging just 37%, dipping to an all-time low of 35% in 2010 and 2011.

In comparison, the global average is around 60%. The corresponding figures for the US, the EU and India are 68%, 52% and 60%, respectively. Even for so-called export-heavy countries like Germany and South Korea, household consumption accounts for 49% of their GDP.

... there has been a consistent decline in the role of private consumption in China’s economy.

Interestingly, this was not always the case with China. Between 1952 and 1977, just before reform and opening up, household consumption made up 58% of the country’s GDP, in line with the global average. In the period following the reforms in 1978 and before China’s accession to the WTO in 2001, the average percentage contribution dropped to 49%. Finally, in the post-WTO accession period, the average stands at 39%. Thus, there has been a consistent decline in the role of private consumption in China’s economy.

Examining the aggregate values of private consumption further exposes glaring differences between China and the rest of the world. China’s aggregate household consumption today stands at ~US$7 trillion. But this is abysmally low for a US$18 trillion economy. In comparison, the US, with a GDP of ~US$29 trillion, boasts of household consumption of over US$19.5 trillion. The corresponding figure for the EU, at ~US$20 trillion GDP, is ~US$10.4 trillion.

In China’s case, an excessively high savings rate has translated into high investment rates.

More interestingly, the US equalled China’s current consumption levels at around US$10.58 trillion of GDP (2001). India, whose household consumption currently stands at ~US$2.4 trillion, will likely equal China’s current consumption levels at US$11.6 trillion of GDP.

The need to spend more, save less

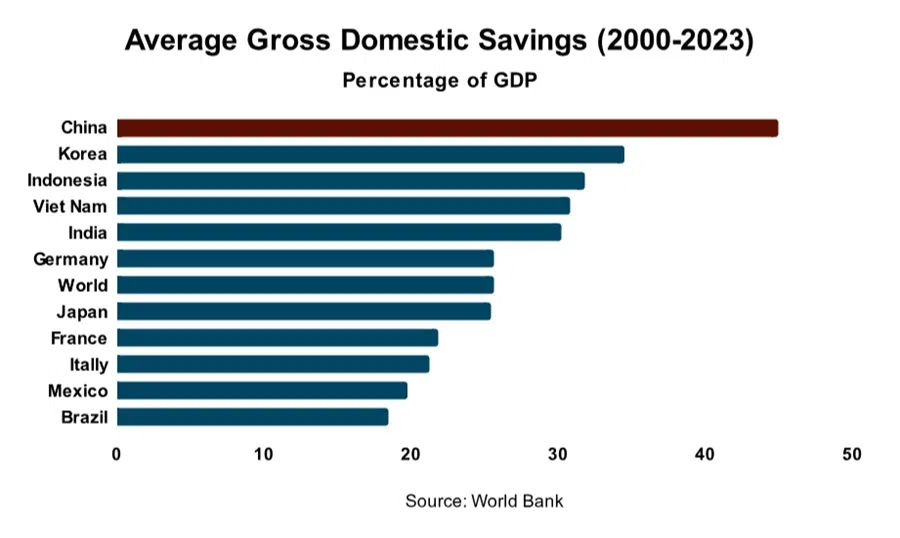

In order to ramp up its private consumption significantly, China will also need to tweak its domestic savings rate. Against the global domestic savings rate that averaged 26% between 2000 and 2023, the corresponding figure for China during the same period stood at 46%. Savings and consumption share an inverse relationship. Thus, the only way to amass an extremely high savings rate is to subdue domestic consumption.

There are, of course, several reasons, including cultural and social factors, that can impact savings rates. However, these should not obfuscate the focus on policy. A significant reason for the high savings rate in China is the party-state’s deliberate policy of financial repression, which entails forcing citizens to save more so that investment rates in the country can remain high. Thus, China’s consumerism is suppressed.

Thus, for China to emerge as a mega-sized consumption powerhouse, its investment rate needs to decline.

The investment rate quandary

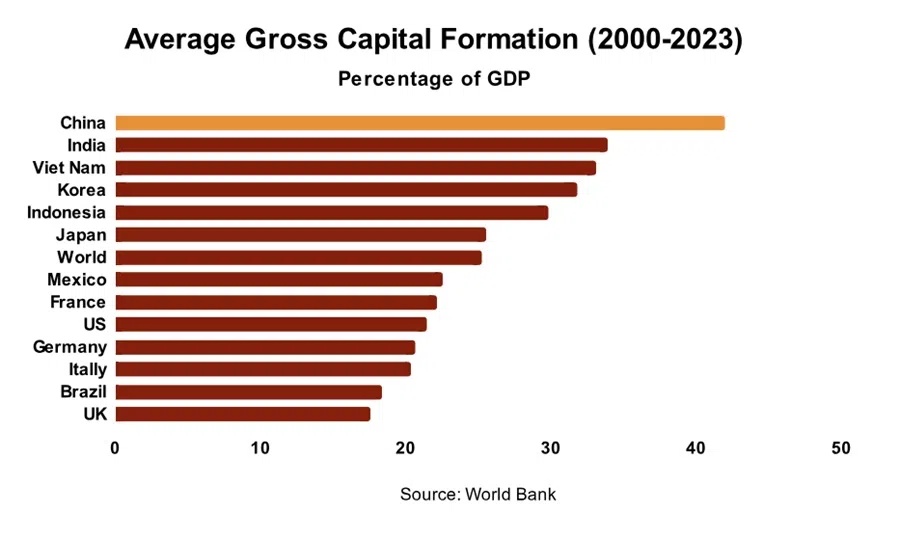

Finally, a country’s investment rate is positively linked to its domestic savings. In China’s case, an excessively high savings rate has translated into high investment rates. Since the turn of the century, China has sustained an extraordinary investment rate of 43% on average.

During this period, the global investment rate averaged 25%. And no other country has averaged an investment rate higher than China during this period. The only country to come close to this figure was India, averaging around 38% between 2004 and 2014.

The investment rate in China has remained high because savings have remained extremely high, which in turn was made possible by suppressed consumption. Thus, for China to emerge as a mega-sized consumption powerhouse, its investment rate needs to decline.

But this presents an irreconcilable dilemma for the Chinese leadership. High investment rates over the decades have been instrumental in propelling Beijing into becoming a manufacturing powerhouse. The leadership regards its manufacturing prowess as a key tool in navigating a Western-dominated global financial system.

The unravelling of the US-China trade war has further reinforced the notion that Beijing needs to not only hold onto its manufacturing strength but also continue to expand on it. This will require China to maintain its investment rate at the current levels, thereby hindering plans to significantly expand domestic consumption.

Thus, Li Qiang has a difficult choice. China can choose to either become a mega-sized consumption economy or continue being a manufacturing powerhouse. It cannot be both.