Where does Europe go now? US retreat, China doubts and a military pivot

Caught between a disengaged US and a complex relationship with China, the EU is pursuing both rearmament and rapprochement — a precarious balancing act fraught with distrust and uncertainty, says Italian academic Alessandro Albana.

“There is great chaos under heaven and [thus] the situation is excellent.” This popular quote of Mao Zedong’s may very well describe the current state of global affairs, especially after President Donald Trump took office in Washington last January. The situation, however, is far from excellent.

Trump and his administration are wasting no time fulfilling the promises made during the electoral campaign: US domestic politics has been dominated by anti-immigration and anti-migrant policies, while the world is provided with early, yet plentiful, bites of what “America First” would eventually look like.

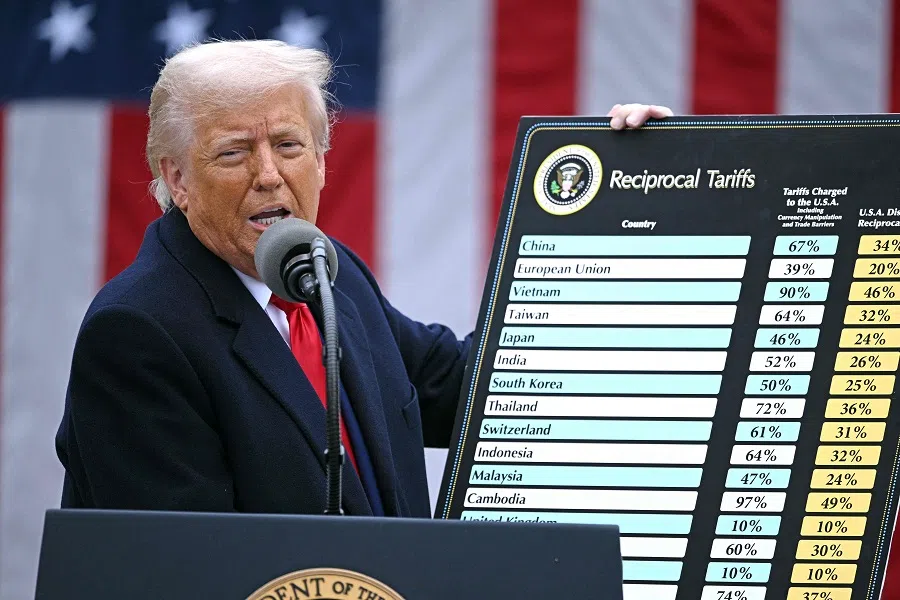

Canada, China and Mexico are testing their negotiation capabilities against US tariffs; Ukraine’s leader, Volodimir Zelenskyy, gained worldwide attention as the most prominent victim of President Trump and Vice-President Vance’s diplomatic temper; and Russia has found in the US an unlikely interlocutor. Arguably, European leaders are experiencing the greatest sense of discomfort and unease.

... the EU’s strategy appears simple and tragic at the same time: to serve as a catalyst for increasing security momentum and expenditures among its member states.

The EU’s ‘simple and tragic’ response

The Trump administration’s dramatic shift in US foreign policy is surprising to few who are familiar with US politics. In contrast, the European Union (EU)‘s reaction has been shocking to many.

As a consequence of Trump’s televised dismissal of President Zelenskyy and the US trumpeted appeasement with Russia, the EU’s strategy appears simple and tragic at the same time: to serve as a catalyst for increasing security momentum and expenditures among its member states.

The programme, unveiled by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, goes by the name “ReArm Europe” and member states are urged to “increase their defence spending by 1.5% of GDP on average” in order to “mobilise nearly 800 billion euros for a safe and resilient Europe”.

Since EU member states lack the budgetary capacity, funding for the EU Cohesion Policy — which aims to strengthen economic, social and territorial cohesion in the EU and correct imbalances between countries and regions — may be redirected for this purpose.

Fears of security and financial instablity

There are several reasons why various criticisms have been levelled at ReArm Europe. First and foremost, there are fears of escalating tensions and an ensuing arms race with Russia, resulting in additional tensions and instability rather than stronger security guarantees. In economic terms, many have voiced concerns about the devastating effects on EU member states fiscal capacity, public debt, and welfare. The EU champions austerity and strict obligations on its member states’ budgetary policies, making such concerns all the more compelling.

“... the EU is paving the way for a financial bubble by resorting to rearmament, which is rapid, measurable and widely supported by the liberal-conservative intelligentsia.” — Professor Alessandro Volpi, University of Pisa

Finally, some experts see ReArm Europe as an intentional opportunity for the EU to create a financial bubble, which could create short-term gains but can lead to instability if not managed carefully. In an interview with the author, Professor Alessandro Volpi of the University of Pisa, an expert of international economy, described the programme as the EU’s strategy vis-à-vis a looming crisis of the US’s and EU’s stock markets: “President Trump’s stance on finance and global affairs are provoking shocks on global financial capitalism. In response, the EU is paving the way for a financial bubble by resorting to rearmament, which is rapid, measurable and widely supported by the liberal-conservative intelligentsia.”

Economics and rapprochement with China

The announcement of ReArm Europe might seem like a defining moment for the EU’s posture in global affairs (not foreign policy: if the EU has any, it is extremely limited and ineffective), signalling a shift towards a more assertive role amidst deteriorating transatlantic relations.

While this move suggests a bid for greater influence in the unipolar contest for hegemony — or perhaps survival — the reality is more nuanced. EU authorities appear to be exploring a tentative consensus with Beijing, focused primarily on trade and economic relations, complicating the overall picture.

In early March, while von der Leyen unveiled ReArm Europe, the European Parliament lifted restrictions on EU officials meeting with Chinese counterparts. Though limited in scope, the event was seen as a sign of the EU authorities’ goodwill in establishing more positive relations with Beijing after years of increasing mutual unease in the diplomatic and economic realms.

Earlier this year, von der Leyen stated that “there is also room to engage constructively with China”, setting an unprecedented tone in the Commission’s approach to EU-China relations during her office. Similarly, the President of the European Parliament, Roberta Metsola, called for mending fences and strengthening dialogue with Beijing. The US disengagement from Europe appears to have influenced the EU’s reassessment of the importance of its relations with Beijing.

Like China, the EU does not lack contradictory behaviours.

Contradictory behaviours

Chinese officials may be willing to welcome the new, tentative approach announced in Brussels. In February, during the Munich Security Conference, Chinese Minister of Foreign Affairs Wang Yi emphasised that “in the irreversible trend of multipolarity, the scope of cooperation between China and Europe has become broader”.

A few days earlier, however, Beijing named Lu Shaye as representative for European affairs. A former ambassador to France, Mr Lu is considered a “wolf warrior” for his diplomatic record and assertive stance towards the EU. On its part, Brussels proposed to blacklist 25 Chinese companies for the alleged supply of sanctioned goods to Russia. Like China, the EU does not lack contradictory behaviours.

At the time of writing, the EU enjoys a 90-day suspension of US tariffs, while the trade war initiated by President Trump has intensified through multiple rounds, reaching tariffs as high as 145% on Chinese imports. In response, Beijing has imposed a 125% levy on US goods.

During Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez’s visit to Beijing in April, President Xi Jinping took the opportunity to invite the EU to join hands vis-à-vis Washington, to “jointly safeguard the trend of economic globalisation and the international trade environment, and jointly oppose unilateral acts of bullying”. Speaking to China’s Premier Li Qiang, von der Leyen emphasised the key role the cooperation between Beijing and Brussels would play in safeguarding a free and functioning international trade.

Time will tell whether such moves are setting the stage for a rapprochement between Brussels and Beijing, or will trigger substantial consequences on their bilateral relations. In a few days, a new government will take office in Berlin; Chancellor Friedrich Merz will make clear what the next future of China-Germany relations will look like. In autumn, France President Emmanuel Macron is expected to visit China. As the 50th anniversary of China-EU relations is marked in 2025, uncertainty will punctuate much of the celebrations.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)