Four turning points: How Abe got China-Japan relations out of negative territory

Japanese academic Shin Kawashima examines the evolution of Japan-China relations in the eight years under the Abe administration, and concludes that though Abe helped to normalise Japan-China relations, the future development of bilateral relations remains unpredictable and more precarious.

On 28 August 2020, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe announced his intention to resign. He was the longest-serving prime minister in Japan's history, remaining in office for nearly eight years, from December 2012. Considering that from 2006 to 2012, six prime ministers served Japan, changing every year, the Abe administration will be hailed a long-lasting administration rarely seen in Japan.

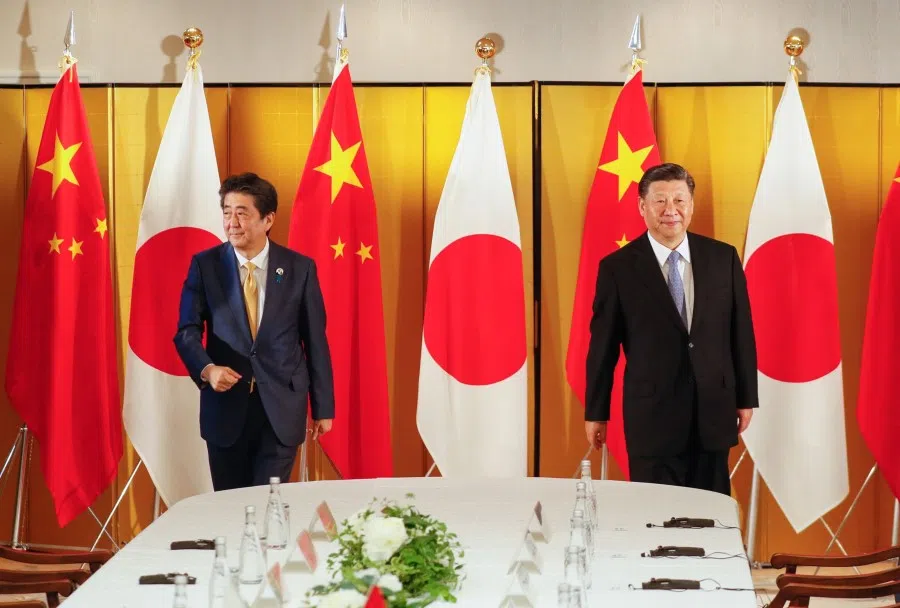

Looking back at Japan-China relations during Abe's time in office, it is fair to say that he improved Japan-China relations - which were frosty when he took office - to the point that a visit to Japan by President Xi Jinping was planned. However, this process was by no means easy. In this article, I would like to look back at Japan-China relations under the Abe administration, mentioning several turning points.

For one year after taking office, Abe made no attempt to improve Japan-China relations. This inaction was arguably mostly intentional.

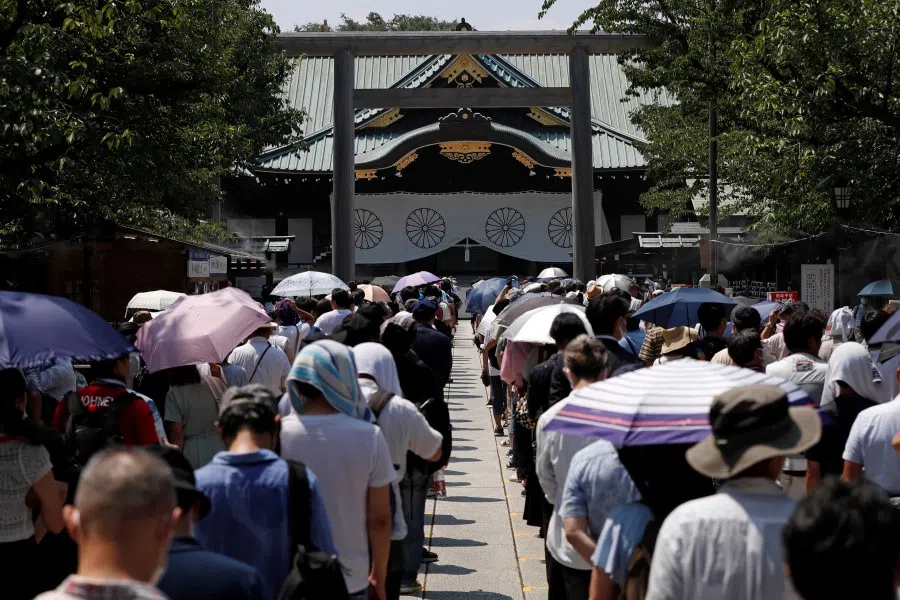

Abe assumed office in December 2012. At the time, Japan-China relations were at one of their worst points, with the Chinese government strongly opposed to the so-called nationalisation of the Senkaku islands, when Japan brought three privately-owned Senkaku islands under state ownership to "maintain the status quo" in September 2012. "At one of their worst points" means an environment that did not really allow for bilateral private sector dialogue let alone bilateral meetings between the leaders of the two countries. For one year after taking office, Abe made no attempt to improve Japan-China relations. This inaction was arguably mostly intentional. Then, in December 2013, Abe paid a visit to Yasukuni Shrine. This can also be described as the moment relations hit rock bottom.

The first turning point came in January 2014. In a policy speech at a Diet session, Abe mentioned improving Japan-China relations. After that, high-profile politicians such as Vice-President of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) Masahiko Komura and former Prime Minister Yasuo Fukuda visited China to explore ways of improving relations. There were also high-level consultations over the Senkaku islands and other issues between high-ranking diplomats from China and Japan and, in November 2014, a four-point consensus on improving China-Japan ties was announced. Abe subsequently visited China to attend APEC China 2014 and the first Japan-China Summit Meeting in three years took place. This summit meeting was the first step to improving relations between the two countries.

Abe spoke of the possibility for cooperation between Japan and China in the BRI, provided four pre-conditions were met: openness, transparency, economic viability and soundness of debtor nation's financing.

The second turning point occurred from August to September 2015. Since the year 2015 marked the 70th anniversary of the end of WWII, a deterioration in Japan-China relations was feared. Against this background, the statement delivered on 14 August by Abe and the speech given by Xi at the Commemoration of the 70th anniversary of the Chinese People's Anti-Japanese War on 3 September indicated that neither side wanted to see a deterioration in Japan-China relations. This does not, of course, mean to say that both parties were happy with the content of each other's remarks. However, the comments that were made were, broadly speaking, acceptable. Abe's success in avoiding inflaming debates about Japan's wartime history in 2015 was hugely significant. In September 2016, Abe visited China to attend the G20 Hangzhou Summit and held a Japan-China Summit Meeting with President Xi.

The third turning point took place from May to June 2017, when Abe steered still further towards improving Japan-China relations. In May, Toshihiro Nikai, Secretary-General of the LDP, visited China with a letter from Abe and attended the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation. The letter contained positive comments about the possibility of cooperation between Japan and China on the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). In a speech delivered at the Future of Asia conference, sponsored by Nikkei, in June, Abe spoke of the possibility for cooperation between Japan and China in the BRI, provided four pre-conditions were met: openness, transparency, economic viability and soundness of debtor nation's financing. This speech elevated Japan-China bilateral relations from summit meetings held on the margin of international meetings to exchanges of visits between the leaders of both countries.

As US-China relations deteriorate, maintaining "amicable" relations between Japan and China is critically important for maintaining balance among the great powers.

The fourth turning point was on May 4, 2018, when telephone talks between Xi and Abe took place. Whilst telephone talks between the Chinese premier and Japanese prime minister had taken place before, telephone talks between the Chinese president and Japanese prime minister were unprecedented. These talks were held directly before Premier Li Keqiang was due to visit Japan for the Japan-China-ROK Trilateral Summit and this "unprecedented" telephone summit was itself the green light for improvement of Japan-China relations. In October 2018, directly after Vice President Mike Pence had delivered a speech criticising China amid deteriorating US-China relations, Abe made a productive trip to China, opening up the possibility of Japan-China economic cooperation projects by the private sector in third countries.

Current Japan-China relations can still be described as being the "amicable" relations seen since this fourth turning point so to speak. As US-China relations deteriorate, maintaining "amicable" relations between Japan and China is critically important for maintaining balance among the great powers. In 2019, Xi visited Japan to attend the G20 Osaka Summit. Xi had been due to visit Japan again in the spring of 2020 but the visit was postponed due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

The improvement of Japan-China relations under the Abe administration was an improvement from negative territory to zero, or in other words, normalisation and Japan-China relations cannot really be described as closer.

Looking back on Japan-China relations over the course of the Abe administration, which lasted nearly eight years, it is fair to say that this period was characterised by improvement in Japan-China relations. The period marks a recovery in relations from their lowest point and the Abe administration's achievement was basically to put exchanges between the leaders of both countries more or less back on track.

However, the improvement achieved over the past eight years can also be described as nothing more than a normalisation of relations. It is not as if relations have returned to how they were in 2008, for example, when Japan-China relations were considered to be extremely amicable and the Understanding on Japan-China Joint Development in the East China Sea (June 2008 Agreement) was also formed. Already, by 2010, China had surpassed Japan in terms of GDP and a return to 2008 was no longer on the cards.

Furthermore, even though Japan-China relations improved under the Abe administration, the level of Chinese activities in the waters around the Senkaku islands increased and the rate of activity of the People's Liberation Army Naval Air Force near Japan was also higher. The improvement of Japan-China relations under the Abe administration was an improvement from negative territory to zero, or in other words, normalisation and Japan-China relations cannot really be described as closer.

Currently, public attitudes towards China in Japan are still extremely negative but close economic ties underpin relations between the two countries. The next prime minister will also face the same situation. It remains to be seen how the next administration will capitalise on the Abe administration's "achievement" or, indeed, whether or not it will.

Related: Post-Abe: Japan's first-rate society will be ballast for stable China-Japan relations | Widening perception gap between Japan and China since Covid-19 outbreak | Cancelling Xi Jinping's visit to Japan? Vested interests split views of Japanese politicians | Japan is not decoupling from China

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)