The Opium Wars: When China's 'century of shame' began

Pain. Humiliation. Injustice. These are the words that Chinese generally associate with the two Opium Wars, which resulted in the infamous unequal treaties that ultimately gave Hong Kong to the British for 100 years. Historical photo collector Hsu Chung-mao sheds light on this defining period of China's history.

(All images courtesy of Hsu Chung-mao)

The first military conflict between modern China and the West was the First Opium War (1839-1842). The war marked the beginning of a historical chapter of humiliation for China at the hands of the West, and moulded the psyche of the Chinese people. Only by understanding the impact of this war on the Chinese people can one truly understand their world view and sense of mission.

Opium originated in Arabia, and was brought into China during the Tang dynasty by Turkish and Arab traders. At first, it was used only as medicine, but during the Ming dynasty, the practice of smoking opium mixed with tobacco was brought in from Nanyang (Southeast Asia). Opium imports to China increased as the Portuguese ventured east, and taxes were levied during the time of the Wanli Emperor. However, the damaging effects of opium on the body had drawn attention.

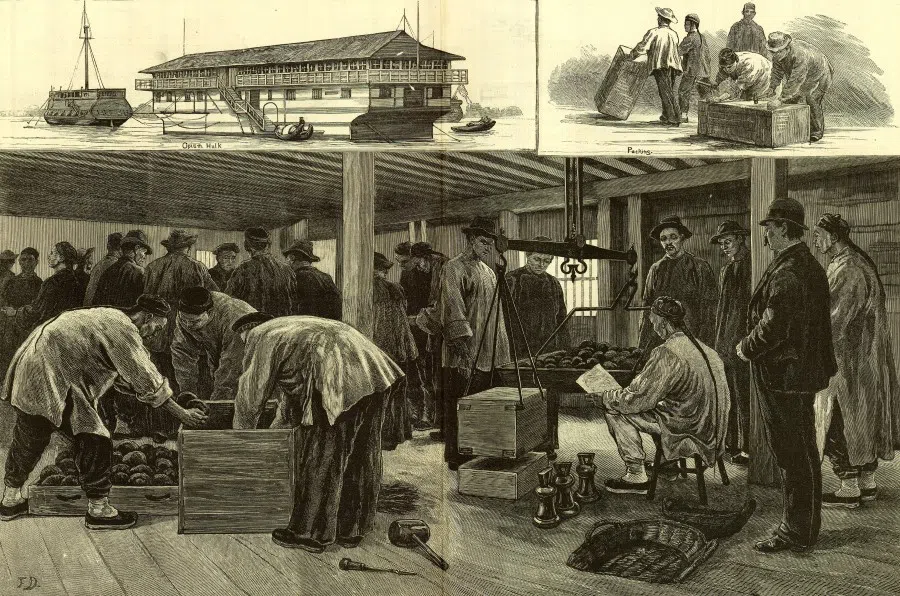

Late in the reign of the Qianlong Emperor during the Qing dynasty, the East India Company won exclusive rights to trade opium, and sold the drug aggressively. China's silver flowed out of the country, and the people suffered while morale declined. In the imperial court, there was a movement to ban opium.

After the Opium Wars, Britain exported a lot of opium to China for handsome gains, which contributed to the wealth of its empire.

Incurring the ire of the British

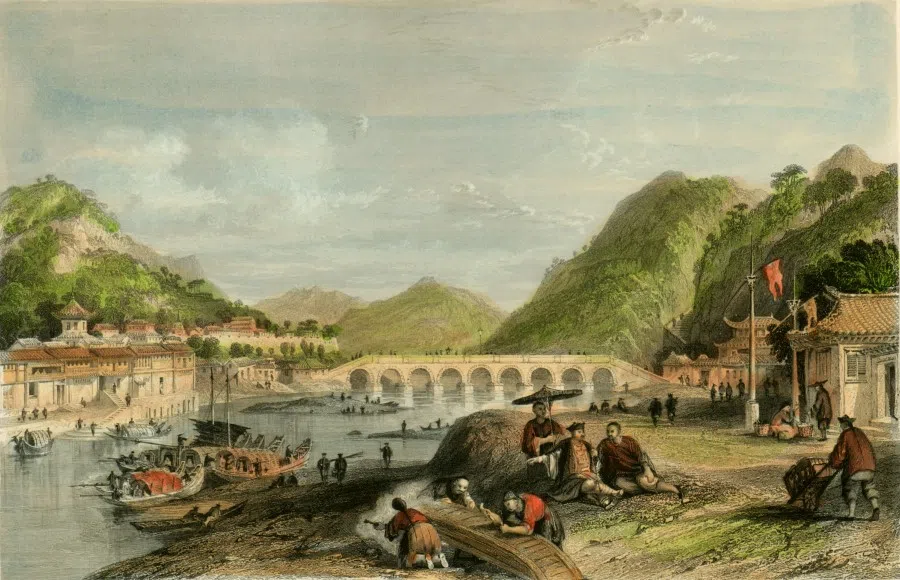

In 1838, the Daoguang Emperor of the Qing dynasty ordered Lin Zexu, the viceroy of Huguang, to go to Guangdong province and enforce a ban on opium. Lin was bold, decisive, and dutiful - on arriving in Guangzhou, he ordered foreign traders to surrender their opium, declaring that the value of the opium would be compensated with tea leaves.

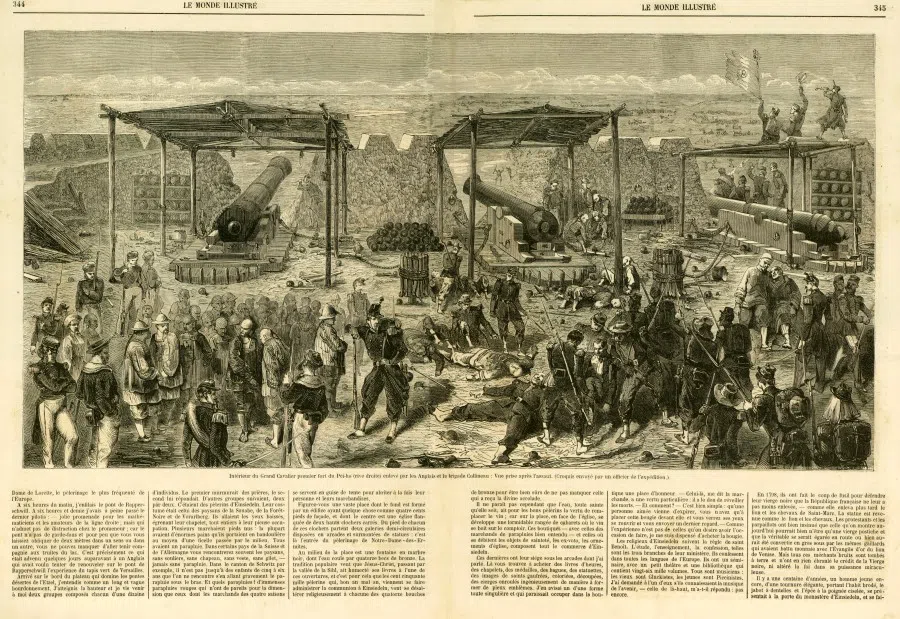

Subsequently, Lin destroyed 20,000 chests of opium at Humen, which angered the British merchants, who banked on a conflict between the British fleet and Chinese sailors. At the time, the British Empire was on the ascent to its peak. Since the Industrial Revolution in the 18th century, industrial technology in Western Europe had progressed rapidly, and it led the world in maritime weapons building capabilities.

Some old imperialist countries that once possessed the most advanced technology and territorial dominance were overtaken during the Industrial Revolution, and seemed to have fallen into a stupor. With its ships and cannons, the British Empire easily defeated ancient civilisations in Central Asia and India, while China was just another sleeping lion that had yet to be awakened.

The seizure and destruction of opium by Chinese local officials stirred anger among the ruling party and opposition in Britain, who felt that it was an "act of aggression" by China against the British. Sentiments were running high and there were calls for war against China. During the parliamentary debates, some opposition members did not agree to fight for drugs and felt that protection should be granted to British citizens instead. However, amid a strong tide of protecting trade freedom, Parliament passed an act of war against China.

In 1840, the British government appointed Admiral George Elliot as commander to lead the navy eastward. Lin Zexu actively prepared and tightened defences, rebuilding batteries and acquiring and deploying warships to cover bases. In May, the British army declared a lockdown on Guangzhou port, before launching a northward offensive on Xiamen and Dinghai, right up to the mouth of the Bai River. Then, they asked to meet Qishan, the viceroy of Zhili, to get China to pay reparations and cede territory.

Where it all started for Hong Kong

After 200 years of peace, the Qing dynasty was like a clay pigeon in its first encounter with the advanced weapons of the British army. The Daoguang Emperor wavered and removed Lin Zexu as envoy, replacing him with Qishan, who merely kept up appearances but hid the facts.

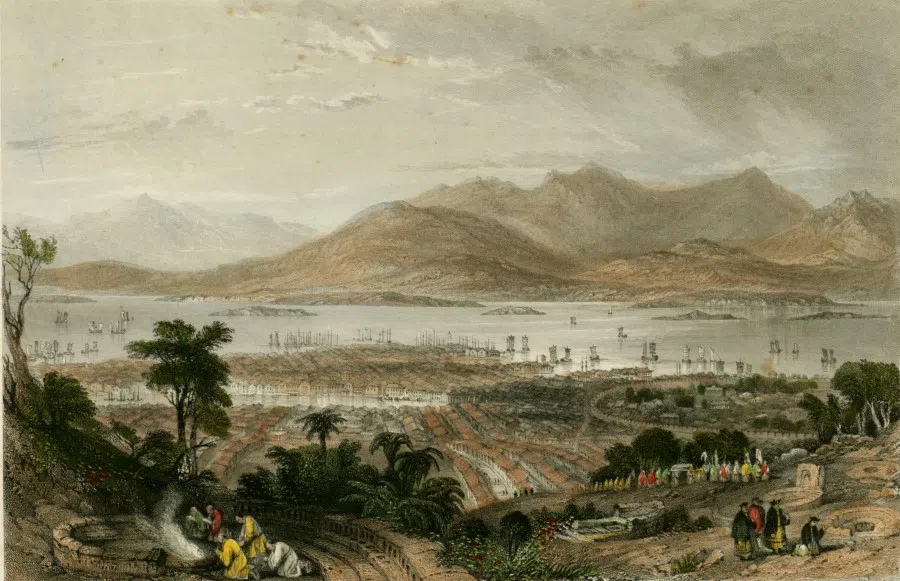

The British then captured Hong Kong, and when the Qing court received the news, it appointed Yu Qian, the governor of Jiangsu, as envoy instead. Defences were set up at Zhejiang, and the war between China and Britain officially began.

By this time, British reinforcements had arrived. In July 1841, the British troops moved north and took Gulangyu and then Xiamen, followed by Dinghai, Zhenhai, and Ningbo. The Qing army was no match for them and suffered heavy casualties. By May 1842, British troops had captured Wusongkou, Shanghai, Jiangyin, and Zhenjiang, and were closing in on Nanjing.

As the British threatened with their northward offensive, the Qing court was forced to sign China's first unequal treaty - the Treaty of Nanjing, which included opening up five ports to trade, reparations for opium, and ceding Hong Kong, starting off a century of national shame.

The Second Opium War followed soon after. In 1854, the envoys of Britain, the US, and France went to Tianjin to engage in direct discussions with the Qing court. Britain wanted to have an ambassador stationed in Beijing, more ports opened up, freedom of travel within China, and amendments to taxes.

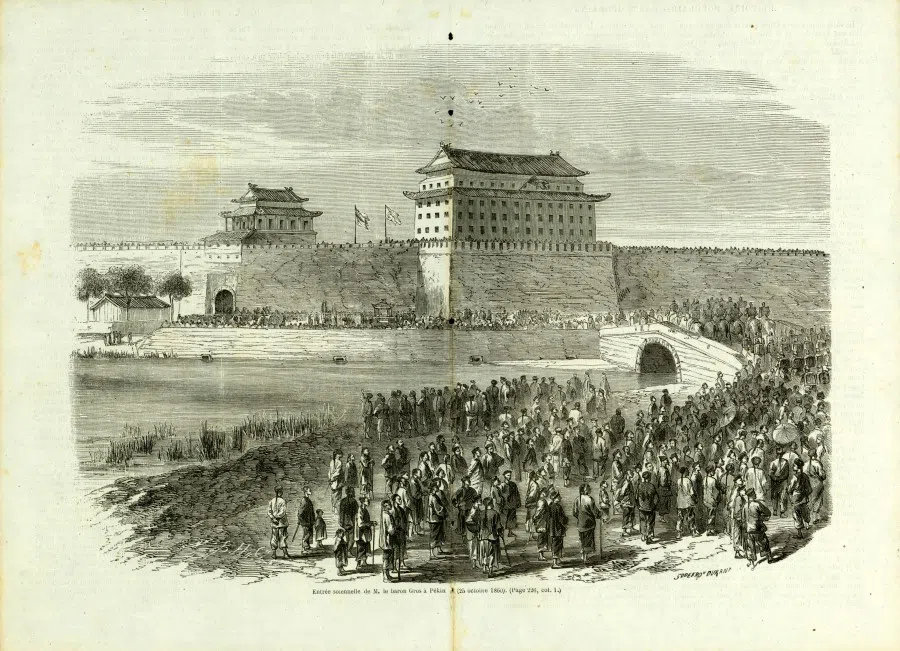

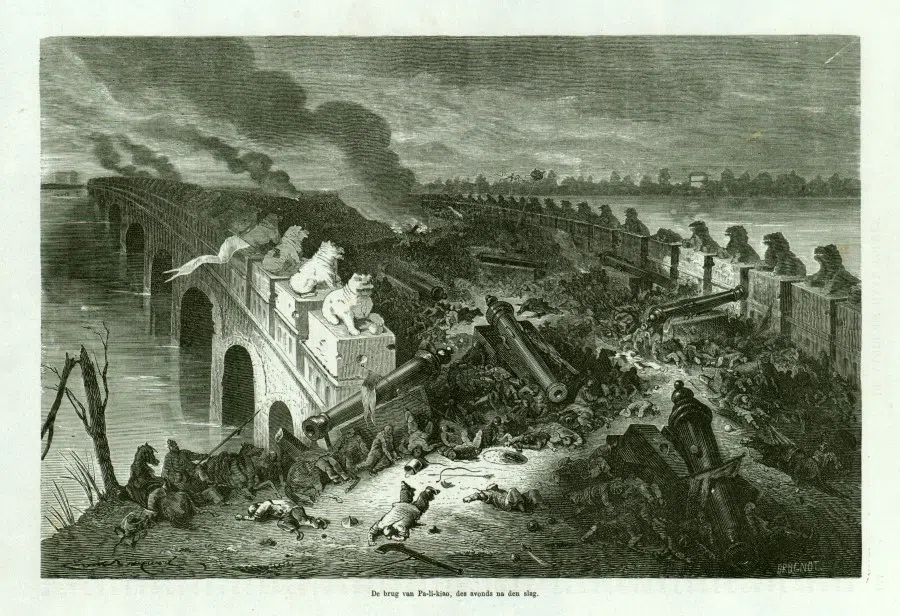

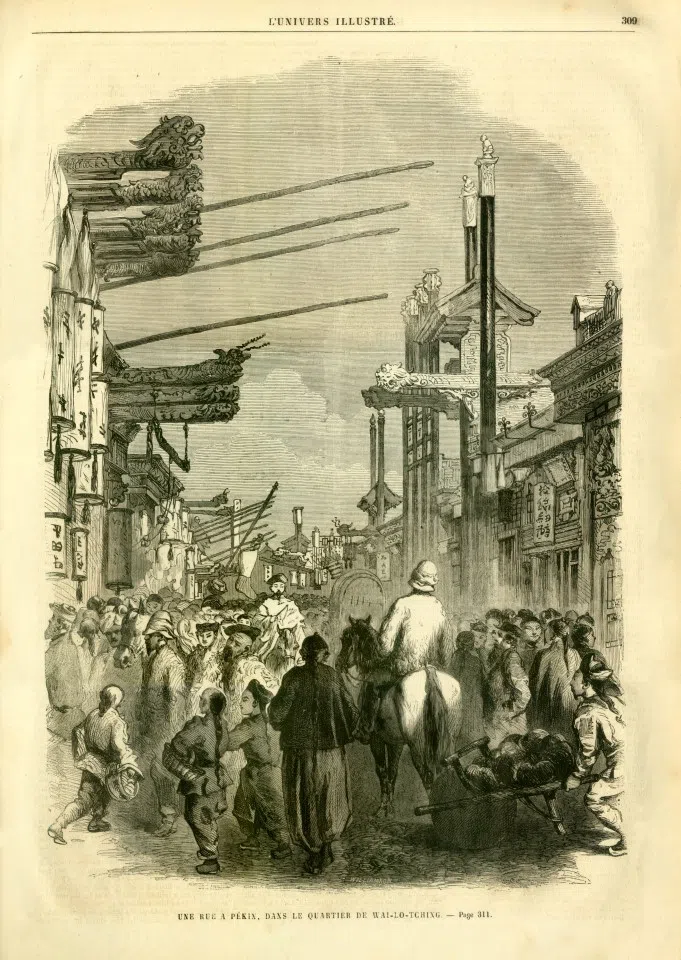

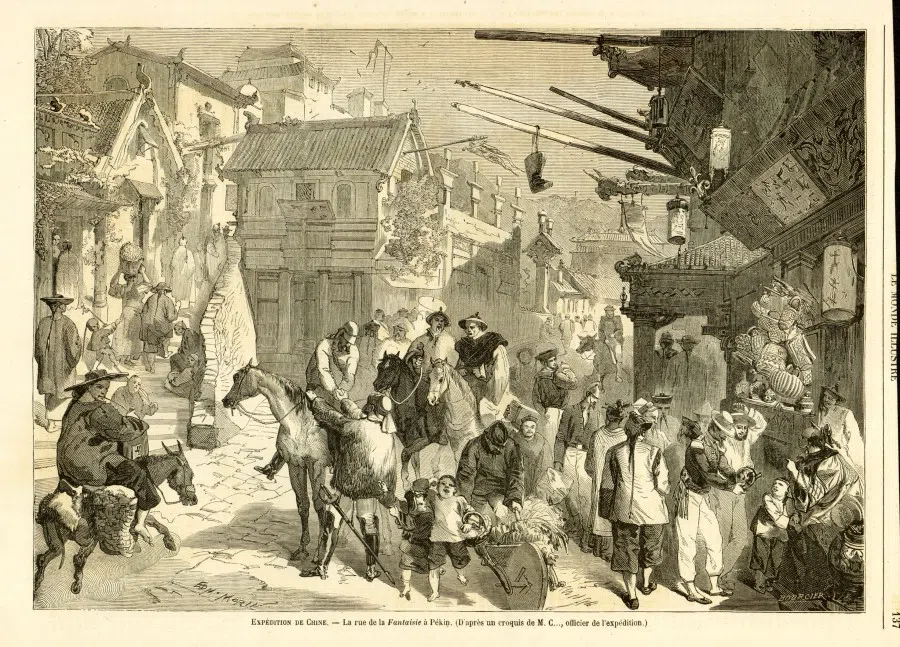

In 1856, the combined army of Britain and France took Guangzhou and sent troops northward to capture the cities at the mouth of the Yangtze River, then deployed military vessels to capture Dagu/Taku port. The military conflict was aimed directly at China's capital Beijing. During the peace talks, China had the British envoy killed, and in retaliation the British-French troops attacked Beijing and sacked the Old Summer Palace or Yuanmingyuan (圆明园), creating a cultural calamity as it went up in flames.

British merchants, backed by the military might of the British Empire, played the role of a legal, armed drug trafficking syndicate that used guns and cannons to overcome a Chinese government that prohibited opium, and forced the Chinese government to compensate the British merchants in full for their losses, and open the doors to opium for these British merchants.

Nightmares of humiliation

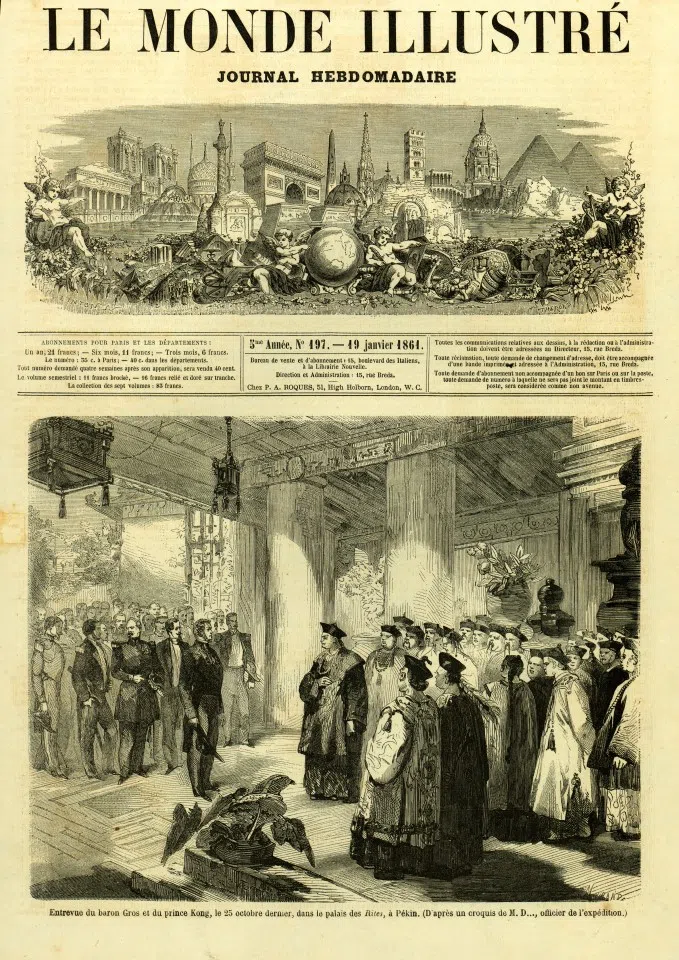

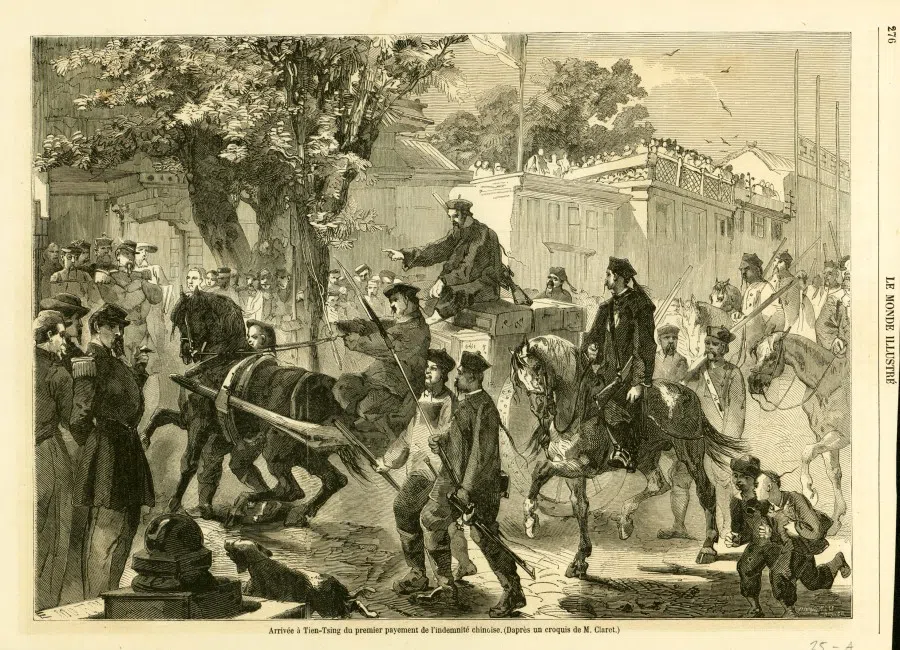

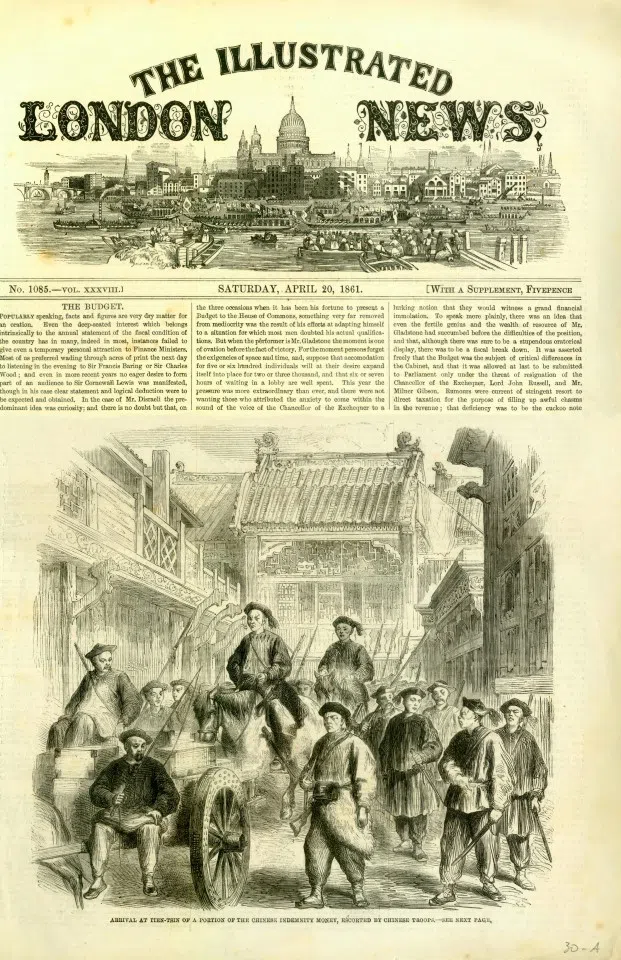

In this Second Opium War, the British and French did not need a large army to claim an easy victory and seize Beijing, the capital of the Chinese Empire. In October 1860, China signed the Convention of Peking with Britain and France. China was made to apologise and allow embassies to be established in Beijing, pay reparations of eight million taels of silver, open up Tianjin, and cede Kowloon to the British.

This is the gist of what happened during the two Opium Wars, of which China and Britain have very different interpretations. Britain calls it a "trade war" because it feels it was a war against China triggered by China violating the rules of normal trade. It intentionally plays down the fact that the product that caused the conflict was a drug called opium. It also hides the fundamental truth that British merchants, backed by the military might of the British Empire, played the role of a legal, armed drug trafficking syndicate that used guns and cannons to overcome a Chinese government that prohibited opium, and forced the Chinese government to compensate the British merchants in full for their losses, and open the doors to opium for these British merchants.

Having foreign ambassadors stationed in Beijing and allowing freedom of travel within China would have done no harm to China, but the Qing court refused. Opium was imported tax-free and hurt the Chinese people, but the Qing court accepted the situation. There was no limit to the bullying by the British and French, while the inept Qing court ruined China.

Perhaps to Britain or the entire Western world, this is just a blip in 19th century global colonialism. The 1986 Hollywood movie Tai-Pan tells the story of 19th century British merchants who sell opium in Guangzhou and meet with roadblocks from the Chinese government. In the movie, the British merchants are portrayed positively, while the Chinese officials who want to stop opium sales are shown as unreasonable and ignorant. As for the historical hero Lin Zexu, he comes across as ugly and bizarre as the fictional villian Fu Manchu. The movie was released in the 1980s, which is not so long ago, and it catered mostly to how Western audiences saw China.

For the Chinese, the lessons of the Opium Wars run heavy and deep, as they opened a chapter of endless humiliation. Over the century that followed, Western imperialist countries took advantage of the conflicts between the various groups and minorities within China, sent troops to occupy China's land, grabbed China's resources, and obstructed China's progress, all in the name of various justifications. Subsequently, the rise of Japanese imperialism also led to Japan joining the ranks of those who bullied China.

It was not until the first half of the 20th century, when the power tussle among Western imperialist countries ignited two world wars, that China found a strategic opportunity to unify and expel enemies and rise again, becoming one of the four victors of World War II, along with the US, Britain, and the Soviet Union.

The Opium Wars had such a profound impact on the psyche of the Chinese people. Every young Chinese student knows of this humiliating chapter in history, and understands how Western countries cited "protecting freedom of trade" to justify forcing the Chinese to import and consume opium. Today, Chinese people are extremely disgusted at how the West pressured China and violated its rights, and have sworn never to allow such humiliation to happen again.

![[Big read] Paying for pleasure: Chinese women indulge in handsome male hosts](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/c2cf352c4d2ed7e9531e3525a2bd965a52dc4e85ccc026bc16515baab02389ab)

![[Big read] How UOB’s Wee Ee Cheong masters the long game](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/1da0b19a41e4358790304b9f3e83f9596de84096a490ca05b36f58134ae9e8f1)