[Photo story] The long road to justice against Japanese war criminals and collaborators

Following Japan's surrender at the end of the Second World War, the horrific military atrocities were brought to light as war criminals were put on trial. Historical photo collector Hsu Chung-mao provides descriptions and images of that period. This article may contain some visually disturbing images.

(All photos courtesy of Hsu Chung-mao)

After Japan announced its acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration, the Far East Allied Command held a surrender ceremony on 3 September 1945 aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay. Shortly on 9 September, the acceptance ceremony of Japan's surrender by China was held in Nanjing.

Subsequently, the Allied headquarters issued orders to arrest war criminals. The Far East Allied Command in Tokyo arrested and prosecuted Class A war criminals, while other regions arrested and prosecuted Class B and Class C war criminals.

In the context of the Chinese theatre of war, this involved the trials of Japanese war criminals responsible for the Nanjing Massacre and collaborators from the Japanese puppet regime under President Wang Jingwei. These trials were aimed not only at bringing justice to bear, but were also a major effort in clarifying the truths of the war.

Trial for the Nanjing Massacre

After three months of intense fighting, the Japanese army occupied Shanghai in late November 1937. Subsequently, nearly 100,000 troops from the 6th, 16th, 18th and 116th Divisions launched a fierce attack on the capital of the Nationalist government along the northern and southern banks of the Yangtze River.

On 12 December, Japanese forces entered Nanjing, where they met with determined resistance from Chinese soldiers and civilians and suffered heavy casualties, prompting retaliatory violence. Hisao Tani, commander of the Japanese 6th Division, allowed his troops to engage in mass killings, raping and looting - this two-week rampage came to be known as the infamous Nanjing Massacre that shocked the world.

In February 1946, China requested for the Far East Allied Command to arrest Tani as a Class B war criminal and extradite him to China. In September, the Nationalist government transferred Tani from Shanghai to a Nanjing prison, starting the trial for the Nanjing Massacre.

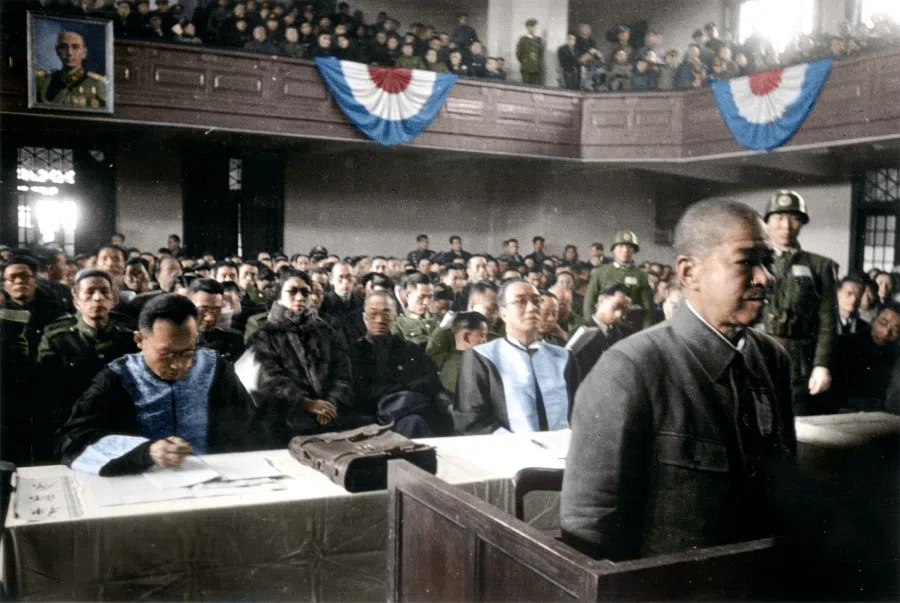

The trial held in early 1947 was presided over by Chief Justice Shih Mei-yu of the Military Court for War Criminals of the Ministry of National Defense. Through investigations including survivor testimonies and exhumation of victims' remains at massacre sites, the court gathered substantial evidence confirming the chilling crimes committed by Tani's forces in Nanjing. Around 200,000 to 300,000 prisoners of war were killed, including through bayoneting, and mass executions and live burials, with about 20,000 women raped and killed. At every public hearing, the courtroom was filled with local and foreign reporters, as well as concerned citizens, to witness the sombre and solemn trial process. (NB: The number of Chinese killed in the massacre has been subject to much debate, with most estimates ranging from 100,000 to more than 300,000.)

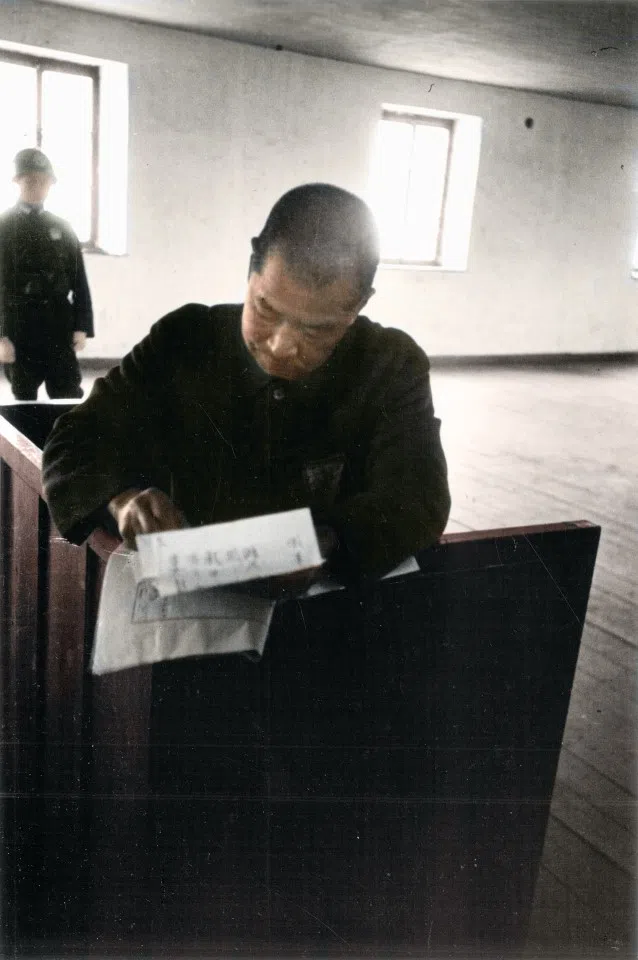

On 26 April, the military court convicted Tani and sentenced him to be executed immediately. Tani was taken to Yuhuatai, where crowds of onlookers were gathered. After he was identified, the downcast Tani faced the firing squad, exactly ten years after his arrogantly victorious rampage in Nanjing.

Killing spree for sport

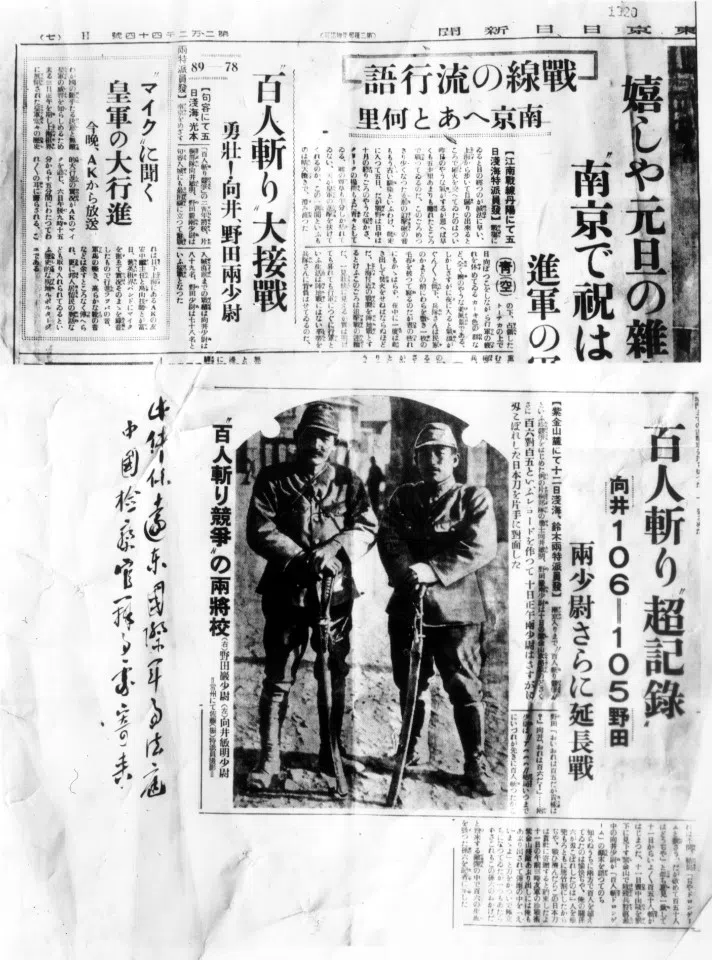

The infamous "100-man killing contest" also left a significant mark in history. On 13 December 1937, the day after the Japanese captured Nanjing, the Tokyo Nichi-Nichi Shimbun reported that Second Lieutenants Toshiaki Mukai and Tsuyoshi Noda had engaged in a competition to kill 100 enemies before entering Nanjing. By the time they attacked Purple Mountain (Zijin Mountain, 紫金山) on 12 December, they had met their target.

At noon on 10 December, they met with notched swords in hand, and Noda said, "Hey, I've killed 105 people, what about you?"

Mukai replied, "I've killed 106!"

The two laughed. While Mukai was up by one, they did not know who had reached the 100 mark first, so they extended the target to 150 people.

This chilling report illustrated the brutal mindset of Japanese soldiers at the time, the praise by Japanese media for their killing spree, and the horrific consequences of the combination of these factors. Following the Japanese newspaper report, the two soldiers found sudden fame and even wrote a tome featuring their wartime atrocities, furnished with photos of the military weapons they used to kill.

Based on wartime reports in Japanese newspapers, the Nanjing military court extradited Mukai, Noda and another officer, Gunkichi Tanaka, to China for prosecution. During the trial, these Japanese officers, who had once killed without blinking, became gentle and well-mannered, hoping to gain favour from the Chinese. They vehemently denied killing innocent people, claiming that the reports in the Japanese newspapers were merely "exaggerations" and "jokes". The court rejected their arguments, and on 28 January 1948 sentenced them to death. They were immediately transported to Yuhuatai for execution.

Expelled and marked traitor

Besides Nanjing, the Ministry of National Defense also established military courts to prosecute war criminals in various locations such as Beiping (now Beijing), Shanghai, Hankou, Guangzhou, Taiyuan, Xuzhou and Jinan. Some 700 war criminals were prosecuted, of which 149 were sentenced to death.

Apart from Japanese war criminals, the trial of collaborators was also a major part of historical justice, primarily targeting the Wang Jingwei puppet regime. An early follower of Sun Yat-sen and graduate of the University of Tokyo's Faculty of Law, Wang was known for his bravery. Before the Xinhai Revolution, he had been imprisoned for attempting to assassinate a Qing prince. After the establishment of the Republic of China, he was released and served as Sun's wendan (文胆, a person in charge of drafting proclamations, speeches, press releases and more for senior political figures). After Sun's passing, he assumed high-ranking positions within the Kuomintang (KMT) and the Nationalist government, but his strained relationship with Chiang Kai-shek led him to participate in anti-Chiang activities.

As Chiang gradually rose to prominence within the KMT, Wang became the second most prominent figure, but his actual power was limited due to his lack of control over the military and his fluctuating political stance.

In November 1937, following the Marco Polo Bridge incident, which marked the start of the Sino-Japanese War, Wang held no hope that China could defeat Japan. Amid intense conflict between China and Japan, he proposed a stance of "friendly peace" towards Japan, differing from the Nationalist government's stance of continued resistance. After the Japanese occupation of Nanjing, Japan declared that it would not negotiate with the Nationalist government led by Chiang Kai-shek, indicating its intention to support a puppet government.

In 1938, Wang Jingwei sent representatives to secretly contact Japanese representatives in Hong Kong. Following the capture of Wuhan in November of that year, Japan announced a peace plan, stating its intention to collaborate with a new Chinese regime. In December, Wang went to Vietnam, and from Hanoi, he issued a statement supporting Japan's peace plan, advocating for the end of the war. On 1 January 1939, the Central Executive Committee of the Nationalist government in Chongqing passed a resolution condemning Wang's statement, expelling him from the KMT and issuing a warrant for his arrest. Wang was widely regarded as a traitor and faced public condemnation in China.

Assigning responsibility for justice

Subsequently, Wang Jingwei went to Japanese-occupied Shanghai, where he and several other leaders of puppet organisations established a pseudo government in Nanjing in March 1940, cooperating with Japan's policy of invading China.

By all appearances, this pseudo government had jurisdiction over the areas occupied by Japanese forces, with a cabinet, military forces and civilian administrative institutions; but in reality, it took command from the invading Japanese forces. Its intelligence department was also assisting Japanese forces in arresting and executing anti-Japanese activists, and local security patrol units became oppressive in monitoring civilian activities for the Japanese public security. These traitorous acts were deeply abhorred by the Chinese people.

At the end of 1943, Wang Jingwei sought medical treatment in Japan, but he passed away after his physical condition worsened.

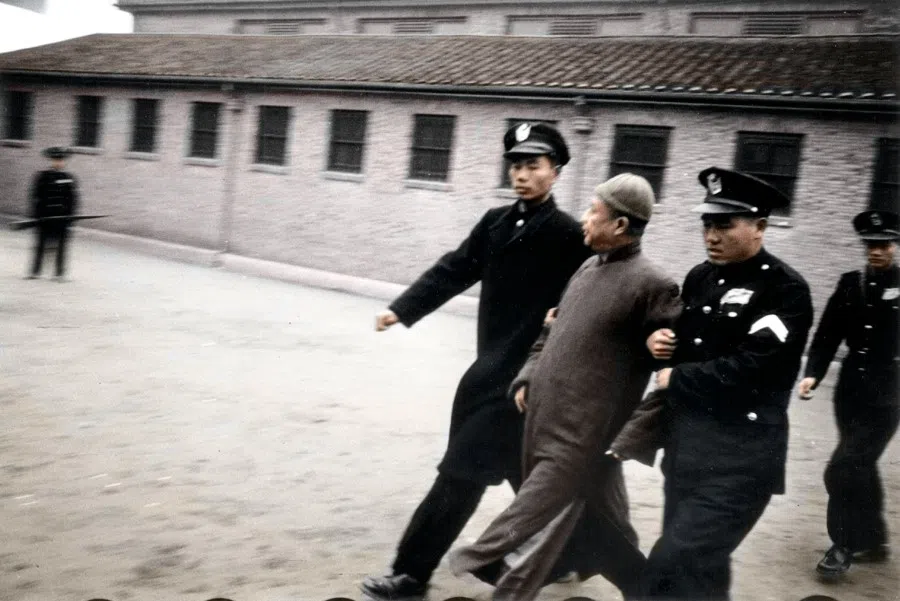

After Japan surrendered in August 1945, the pseudo government was automatically dissolved, and the Nationalist government in Chongqing took control of all institutions and military forces. In September, the Nationalist government arrested members of the puppet government at all levels across the country. Despite Wang's passing, key figures were prosecuted, and most of those in charge of diplomacy, internal affairs, police, security and propaganda were sentenced to death and swiftly executed.

Showing compassion

In the three years following the war against Japan, China conducted trials for Japanese war criminals and collaborators as a preliminary step to investigate and assign responsibility for justice. Indeed, China demonstrated magnanimity as they restricted the scope of dealing with war criminals, despite the tremendous losses China suffered due to Japanese aggression, including around 20 million casualties, incalculable economic losses, and the irreplaceable destruction of homes.

In comparison, approximately 600,000 Japanese soldiers in Manchuria were sent to Siberia by the Soviet Union for years of forced labour, leading to countless deaths. In China, over two million Japanese soldiers were safely repatriated to Japan within a year and a half, a lasting effort towards future Sino-Japanese friendship and global peace. Perhaps the following profound statement in Chiang Kai-shek's victory speech rings true:

"My Chinese compatriots must know that 'not dwelling on past grievances' and 'being kind to others' are the noble virtues of our nation's tradition. We consistently maintain that we recognise the militaristic warlords of Japan, and not the Japanese people, as enemies. Now that the enemy's forces have been collectively defeated by our allied nations, we will certainly hold them accountable for faithfully carry out all the terms of surrender, but we do not intend to seek revenge.

"Furthermore, we must not humiliate innocent people. We should only express compassion for those who were deceived and coerced by the Nazi warlords, enabling them to free themselves from their errors and wrongdoings. It should be understood that responding to past violence with violence, or answering their former sense of superiority with insults, only perpetuates an endless cycle of vengeance. This is not the goal of our virtuous and righteous forces, and it is something that every one of our military and civilian compatriots should note."

Related: [Photo story] From admirer to conquerer then equals: Japan's evolving relations with China over the centuries | Soong Mei-ling and the flying tigers: When China and the US fought shoulder to shoulder | Political significance of former Taiwan President Ma Ying-jeou's China visit | Tan Kah Kee, Aw Boon Haw and the Second Sino-Japanese War [Photo story]