[Photos] Collapse of the Japanese empire’s ‘Manchu dream’ in northeast China [Eye on Dongbei series]

Northeast China, also known as Dongbei, has always been a crucial region for China’s development, with every move affecting the entire Northeast Asia. Historical photo collector Hsu Chung-mao shares the historical events that impact us even today. This article may contain some visually disturbing images.

(All photos courtesy of Hsu Chung-mao.)

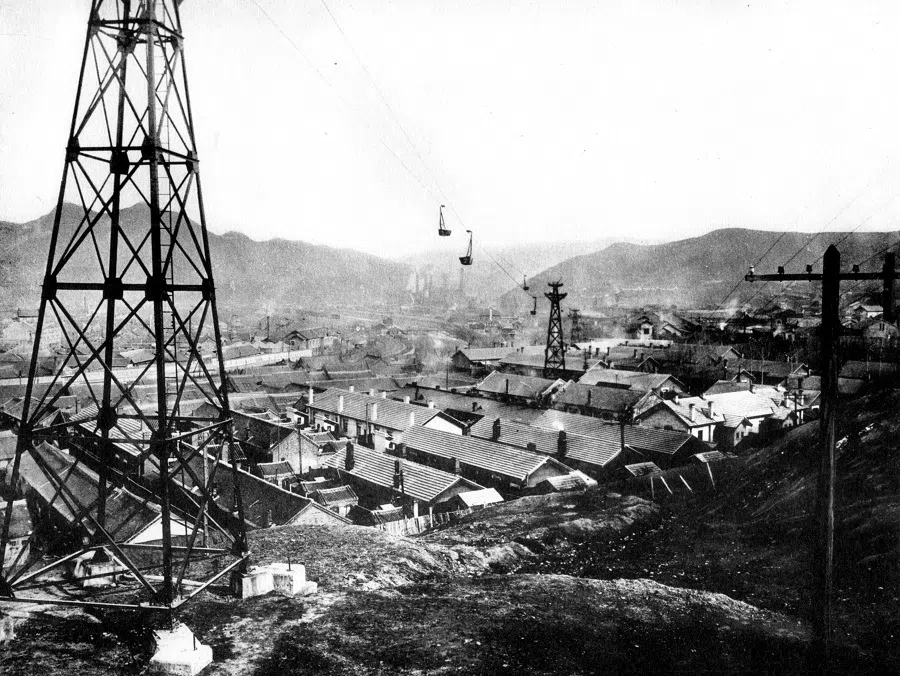

In 1934, Japan launched the high-speed train Asia Express in Manchuria, which ran between Dalian and Xinjing (today’s Changchun), the capital of Manchukuo.

The Japanese-made streamlined steam locomotive was said to be the fastest steam train in the world at the time. The train’s materials, equipment and comfort were adapted to the continental climate of Manchuria and reflected the highest standards of Japanese heavy industry, setting a new benchmark in the history of trains.

Battle Nexus

For the Japanese government, the Asia Express was not merely a high-speed train but also a significant symbol of Japanese propaganda for Manchuria’s development. It was a show of Japan’s major progress in Manchuria to the Japanese people and the international community.

The 14 years or so from the Mukden incident in 1931 and the installation of China’s last emperor Aisin Gioro Pu Yi as head of a puppet government in 1932, to the collapse of the Japanese empire in 1945, were a significant historical period for northeast China and played a crucial role in changing the Northeast Asian situation, laying the foundation for the political order in Asia today.

As early as 300 AD, during the Warring States period, the State of Yan established a prefecture in Liaodong, and subsequent dynasties administered parts of northeast China.

Northeast China borders Outer Mongolia, the Korean Peninsula and Siberia, and has historically been a gathering place for northern nomadic tribes. As early as 300 AD, during the Warring States period, the State of Yan established a prefecture in Liaodong, and subsequent dynasties administered parts of northeast China.

In 108 BC, the Han dynasty sent troops to occupy northern Korea, establishing prefectures and counties, and introducing Han culture to Korea, which was then transmitted to Japan. With the rise and fall of the Chinese empire, the power of the Korean dynasty also fluctuated, sometimes controlling parts of northeast China when it was strong. However, it was still a vassal state of China most of the time.

In 1592, Japanese general Toyotomi Hideyoshi sent troops to attack the Korean Peninsula, with the ultimate goal of attacking Beijing and becoming the new ruler of China. The Yi or Joseon dynasty in Korea was unable to hold out, and asked the suzerain Ming dynasty for help, leading to a seven-year war that ended with the defeat of the Japanese army.

Soon after, Nurhaci, leader of the Jurchen people in the northeast, rose in power. The Jurchen people had previously occupied northern China and established the Jin dynasty, but were later overrun by the Mongol empire and retreated back to the northeast.

About 300 years later, they regained power and launched a comeback, and this time they were a force to be reckoned with. They first attacked Korea, forcing the Joseon dynasty to surrender and pay tribute to the Jurchen people. Then, taking advantage of the weakness and division of China’s Ming dynasty, they launched a large-scale invasion and conquered China, and established the Qing dynasty.

The Japanese people’s spiritual guide was this cult-like belief, with Manchuria being their largest experimental ground.

From Qing dynasty to the Republic of China

During the reign of the first three emperors of the Qing dynasty, which was led by the Manchu people, the borders were greatly expanded to include southern Siberia, Central Asia, Xinjiang, Tibet and other regions, forming the basic layout of China’s territory today.

In the late 19th century, Western powers arrived in Asia with powerful warships and new technologies developed after the Industrial Revolution. Asian countries failed to resist, and were either colonised or defeated, ceding land and paying reparations. Each country sought its own path to reform, with Japan being the most successful. The Meiji Restoration led Japan to rapidly become a progressive nation, but it also followed in the footsteps of Western imperialism and colonialism.

After the First Sino-Japanese War, Japan occupied Taiwan and controlled the southern part of the Korean peninsula, reviving Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s plan to first occupy Manchukuo then conquer China.

However, they encountered another expansionist power: the Russian Empire. After the Russo-Japanese War in 1905, Japan controlled the entire Korean Peninsula and southern Manchuria, and formally annexed Korea in 1910. At the same time, Chinese revolutionaries overthrew the Qing dynasty and established the Republic of China, beginning its path to revival.

Over the next 20 years, China gradually unified, making rapid progress in politics, military, economy, culture and education. Russia’s military power also grew rapidly after the communist revolution, and the global tide of anti-imperialism and anti-colonialism rose, posing a significant challenge to Japan’s expansionist policies.

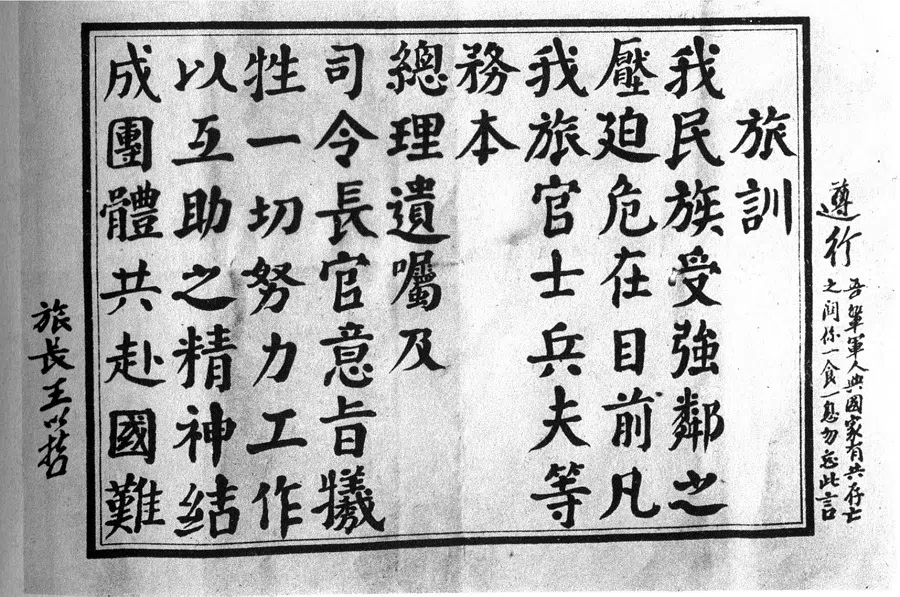

Nevertheless, the Japanese people were intoxicated by the dreams painted by the militaristic government, religiously believing in the divinity of the Japanese emperor and the ultimate rule of the Yamato people over the world. For instance, in his book The Final War, Japanese military philosopher Ishiwara Kanji predicted that Japan would defeat the US in a great war and bring eternal peace and happiness to the world. The Japanese people’s spiritual guide was this cult-like belief, with Manchuria being their largest experimental ground.

By the time Japan was defeated, Manchuria’s GDP had surpassed that of mainland Japan.

Manchuria: a ‘paradise fit for kings’

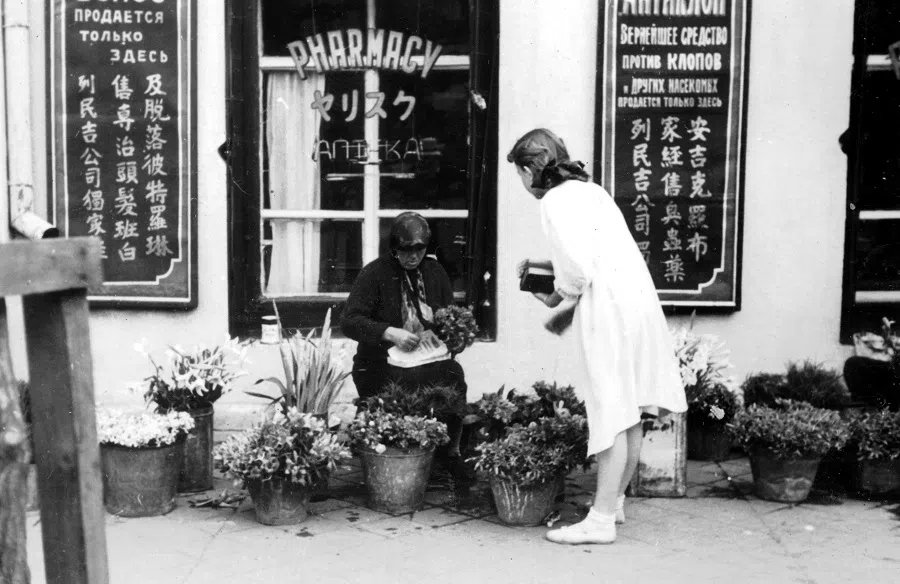

After occupying Manchuria, Japan described it as a “paradise fit for kings”. In terms of technical strategy, Manchuria was rich in iron, coal, heavy metals and agricultural resources, and Japan put its entire national effort into investing heavily in capital, technology and talent in Manchuria.

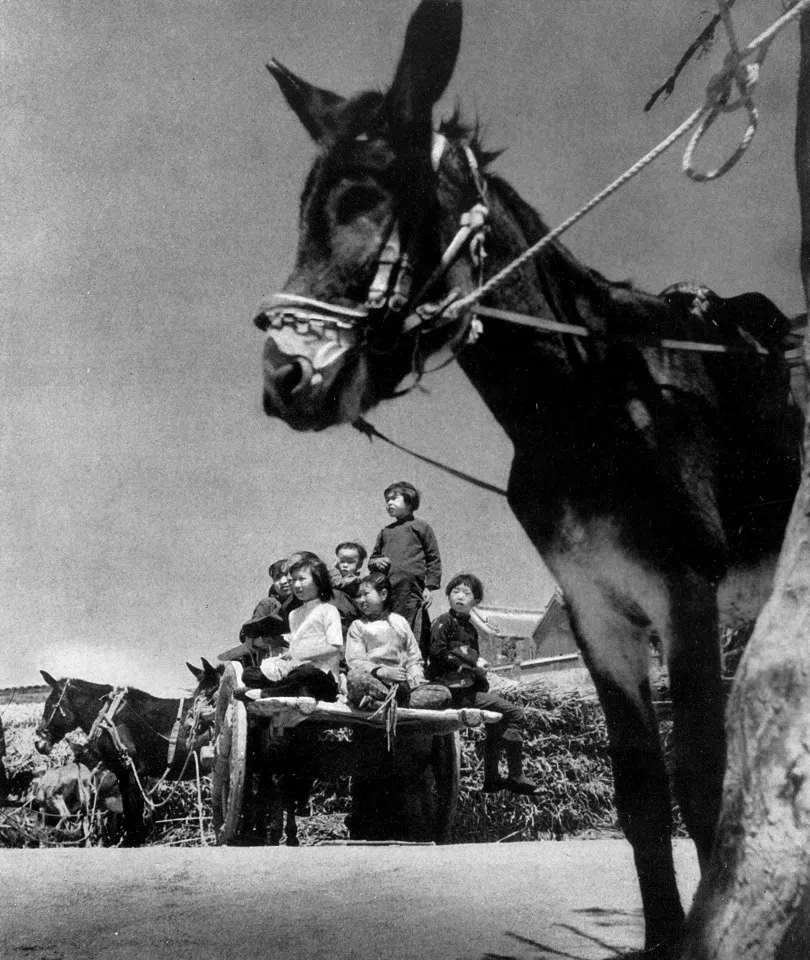

By the time Japan was defeated, Manchuria’s GDP had surpassed that of mainland Japan. Ordinary Japanese citizens frantically bought stocks in the South Manchuria Railway Company and invested in Japanese companies developing Manchuria. Meanwhile, under the Japanese government’s arrangements, hundreds of thousands of Japanese farmers migrated to Manchuria, settling in planned fields and opening up the land.

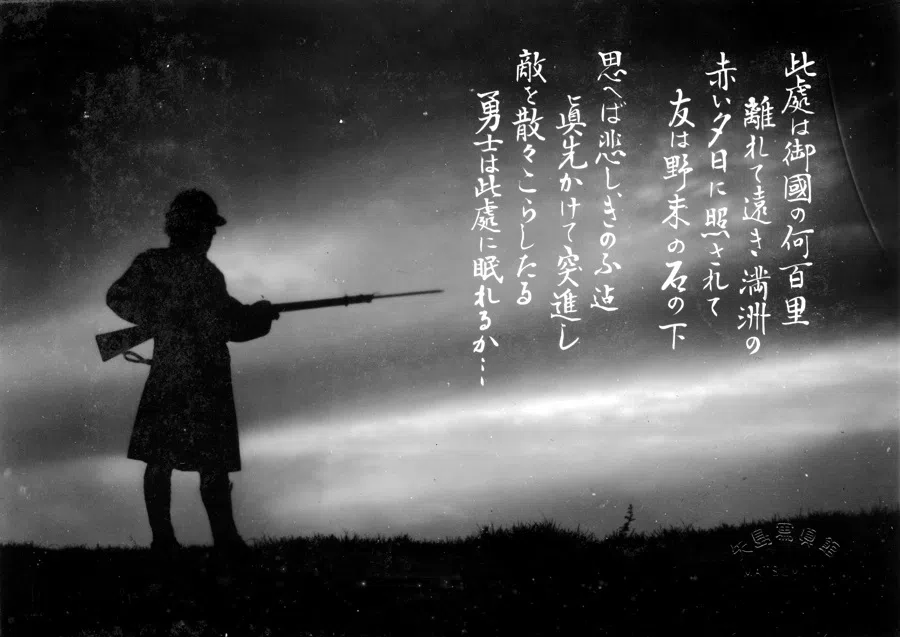

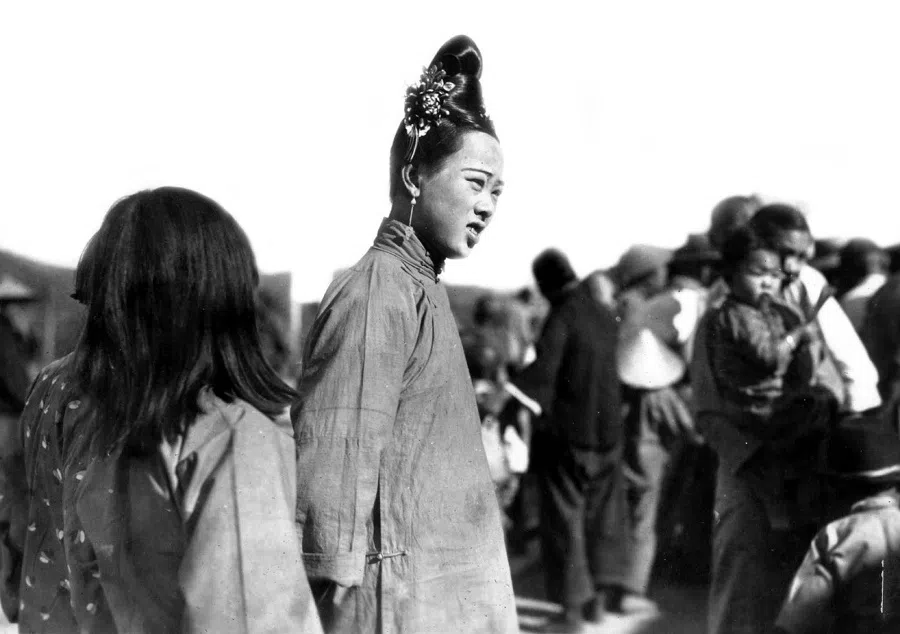

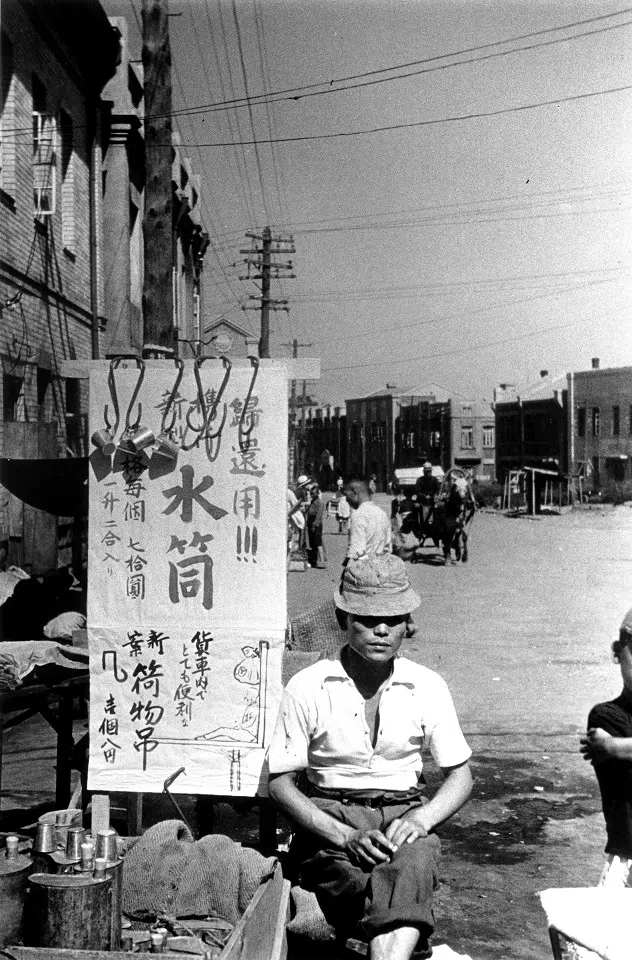

During this period, Japan produced thousands of literary, photographic, journalistic and cinematic works depicting Manchuria as a paradise on earth, where one could achieve ultimate happiness in life.

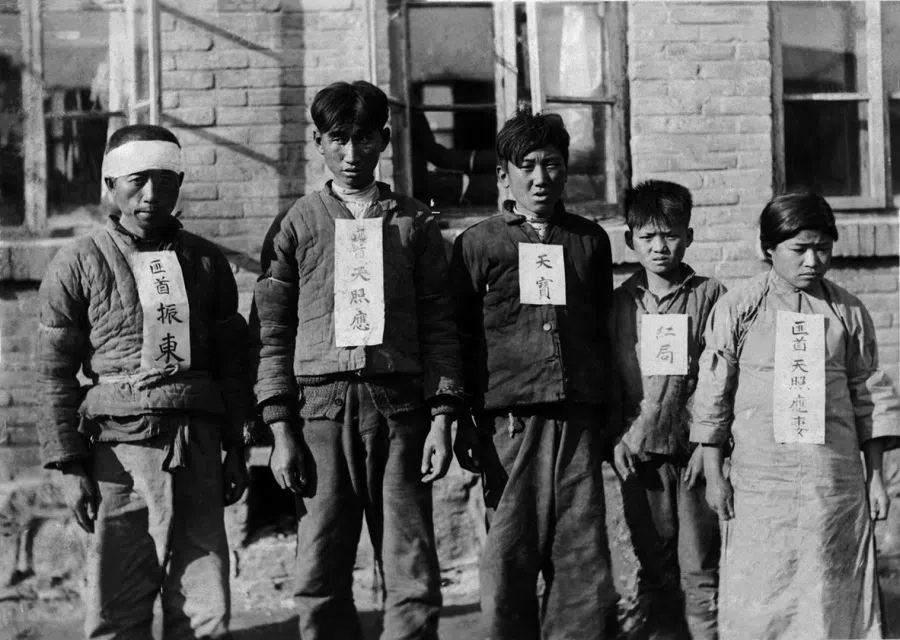

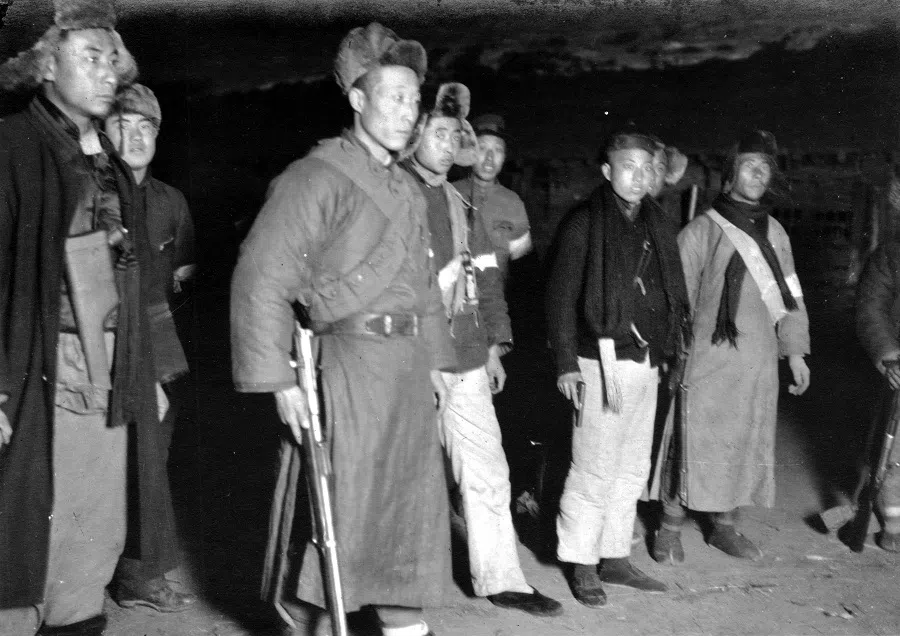

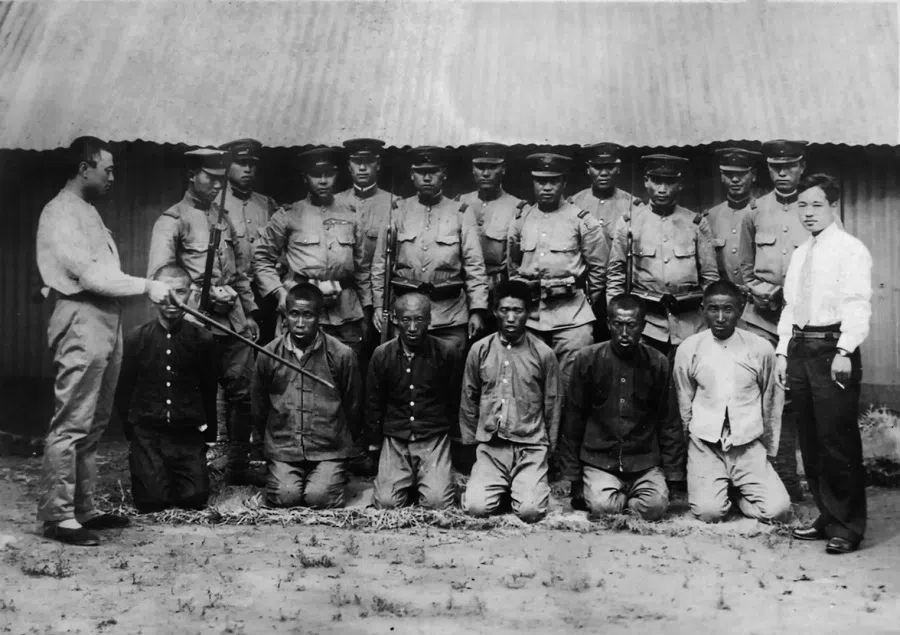

However, behind the rosy picture of life depicted by the Japanese government, there was a dark and ugly side. Japan used extremely brutal methods to occupy and develop Manchuria. In order to completely control Manchuria, Japanese troops pursued armed anti-Japanese fighters in the vast wilderness. Once caught, these “bandits” were cruelly tortured, shot and put to the sword.

The Japanese government controlled the publication of such images, but Japanese military officers’ private albums contained many atrocious photos; they seemingly enjoyed the act, revealing a bizarre and perverted psyche. These photos were exposed after the war, shocking everybody.

Japan also secretly established Unit 731, using Chinese, Koreans and Russians as test subjects for biological experiments, in preparation for large-scale biological warfare against the Allies.

Japan also drove out Chinese farmers by force, and handed over fertile land to Japanese development teams. These sinful acts ultimately led to major historical backlash against Japan.

From northeast China to the rest of the country

In 1945, before Japan’s defeat, the Soviet army occupied Manchuria and sent 600,000 troops from Japan’s Kwantung Army to Siberia as slave labourers, using the same cruel methods Japan had used against their own prisoners of war. But by the time they returned to Japan a few years later, about 90,000 Japanese were forever buried in the ice. Hundreds of thousands of Japanese expatriates were left homeless in the subsequent Chinese Civil War, with many parents leaving their children to be raised by Chinese farmers, leading to the issue of “war orphans”.

Following Japan’s defeat and withdrawal from northeast China, the region continued to play an important role in Asian politics. Due to Japan’s previous major efforts, northeast China had become the centre of China’s heavy industry, including coal, iron, agricultural raw materials, machinery, weapons, automobiles, trains, shipbuilding and the manufacturing of industrial product components, which naturally made it a crucial location for international and domestic political forces.

After the war, the Soviet Union’s Red Army occupied northeast China, and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) urgently dispatched 20,000 troops and political workers to the region. The Red Army received the weapons of 600,000 Kwantung troops, allowing the CCP to establish its own heavy artillery forces and rapidly develop its ability to engage in frontal warfare. This greatly enhanced its combat capabilities.

In May 1946, the Kuomintang (KMT)’s elite troops entered northeast China, and the Soviet army began to withdraw, taking away a lot of Japanese factory machines and equipment. Soon after, a major battle broke out between the KMT and CCP.

The CCP was in control of the heavy industry and military-industrial centre in northeast China, and they marched southward, sweeping across the whole of mainland China within a year.

As the Chinese situation evolved, the CCP forces achieved a comprehensive victory on the northeast battlefield in 1949 and established the Fourth Field Army, the largest, strongest and best-equipped among the CCP troops.

The CCP was in control of the heavy industry and military-industrial centre in northeast China, and they marched southward, sweeping across the whole of mainland China within a year. The following year, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) was established, and the Korean War broke out, involving the US, the Soviet Union and China.

Even after the Korean War, northeast China remained an essential industrial production base for the PRC, supporting a large number of jobs.

In the end, the People’s Liberation Army crossed the Yalu River from northeast China to participate in the war, and the region’s strong industrial foundation provided powerful backing for the war effort.

Even after the Korean War, northeast China remained an essential industrial production base for the PRC, supporting a large number of jobs. The factories and machines left behind by the Japanese continued to operate for decades until China’s opening-up, when its new industrial model developed, and new high-tech centres in computers, aerospace and national defence were established across the country. Only then did the proportion of northeast China’s industrial output gradually decline.

Looking back on the past century, northeast China has always been a crucial region for China’s development, with every move affecting the entire Northeast Asia. The current situation on the Korean Peninsula makes northeast China’s position today even more critical, with its many touching stories amid changing times — the sacrifices and struggles of a people, of life and death and separation of individual families, and the rise and fall of nations, which have all become a microcosm of the history of China and Asia.