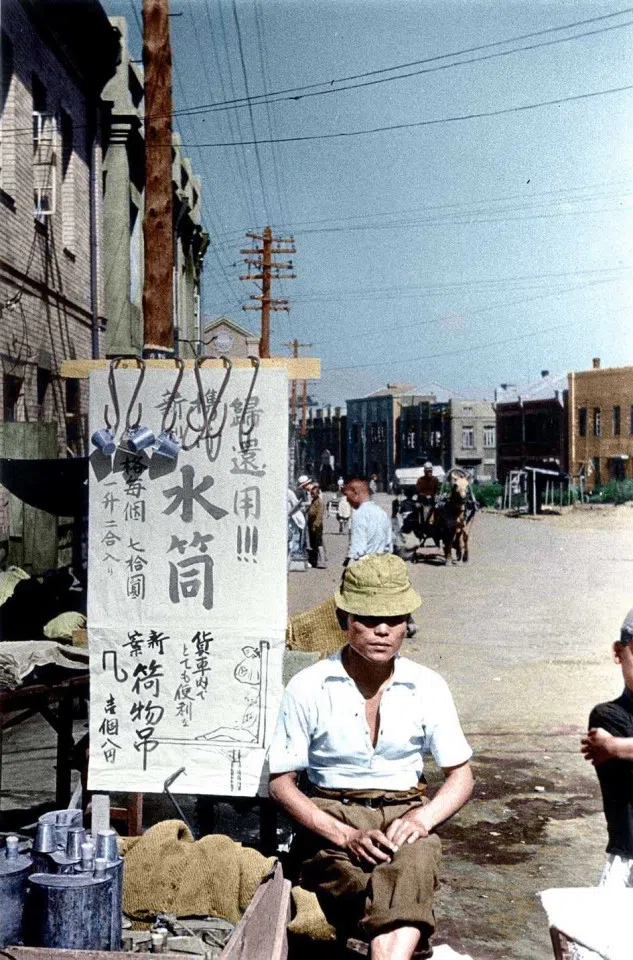

[Photo story] The fate of Japanese POWs and civilians in China after World War II

During the Japanese occupation of China in World War II, the Japanese government encouraged the people of Japan to migrate to China, where they were accorded many privileges as first-grade citizens. But when Japan eventually lost the war, these people found themselves cut adrift in an instant, neither belonging to China nor tied to Japan, especially the children born during the war. Many suffered and even lost their lives as the Soviet army put them into concentration camps and took retaliatory action. Some Japanese still remember the magnanimous policies of the Chiang Kai-Shek government, which arranged at the time for Japanese POWs and other Japanese to be repatriated back to Japan. Historical photo collector Hsu Chung-mao presents photos of the period.

(All photos courtesy of Hsu Chung-mao.)

On 15 August 1945, Japanese Emperor Hirohito went on radio to announce Japan's unconditional surrender under the Potsdam Declaration, to great celebrations by the Chinese people. On 9 September, a grand surrender ceremony of the Japanese troops in China was held in Nanjing, becoming an important day of commemoration for the Chinese. The fact is, this ceremony was the culmination of negotiations between Chinese and Japanese troops.

The surrender

At the point of the Japanese surrender, there were over a million Japanese troops in China. About one-third of them were concentrated in Hunan, facing off against the masses of Chinese troops on the outskirts of China's wartime capital Chongqing in Sichuan province. It made sense then that Hunan became the location of frontline exchanges between Chinese and Japanese troops.

Given the momentous occasion, commander-in-chief of the Chinese Army General He Yingqin and the US chief of staff of Chinese Combat Command Haydon L. Boatner, as well as other commanders, arrived in advance in Zhijiang county in western Hunan province.

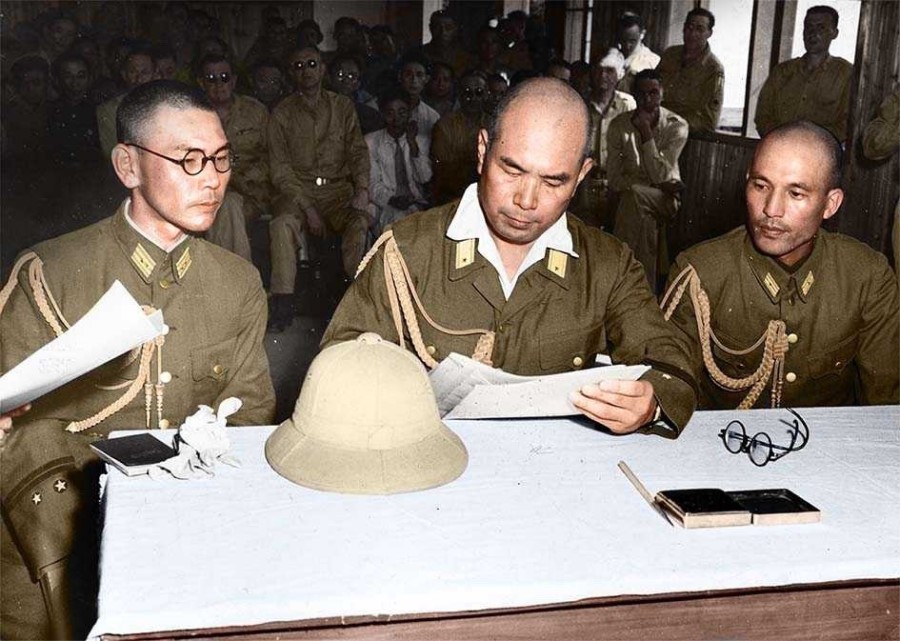

As instructed by the Chinese, on 21 August, a Japanese transport aircraft carrying vice-chief of the general staff of the China Expeditionary Army Takeo Imai and his staff landed at Zhijiang, where the Japanese surrendered to chief of staff of the Chinese Army Xiao Yisu.

Imai handed over a map showing the distribution of Japanese troops, while He read out General Order No. 1 by Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek stating the terms of the Japanese surrender. Both sides then engaged in discussions and arrangements for the surrender of Japanese troops in China and northern Vietnam, following which they were able to relax a little, after finally ending a long and painful war. From that moment, Chinese and Japanese were no longer enemies.

Bearing no grudges

As for how to treat surrendering Japanese troops, Chiang's victory speech made the following important points. "My fellow Chinese would know that not bearing grudges and being kind to others is a noble and valuable characteristic in the tradition of our people. We have always said that only militaristic Japanese warlords are our enemies; the people of Japan are not our enemies. Today, the enemy troops have been defeated by our allies, and we will of course strictly ensure that all terms of surrender are enforced. However, we do not want revenge, nor should we humiliate the innocent people of our enemy country. We can only commiserate with how they were manipulated and driven out by their Nazi warlords, so that they can extricate themselves from mistakes and transgressions. If we respond with violence to our enemies' past violence, and respond with insults to their previous mistaken sense of superiority, that will lead to an unending feud, which is definitely not what our forefathers would want. This is what each one of us needs to be aware of today."

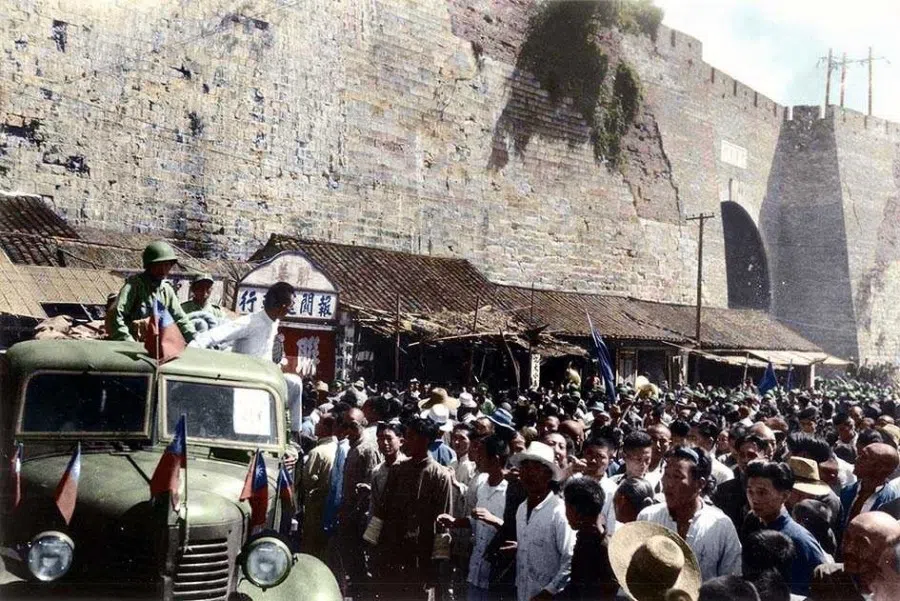

On 29 August, the Chinese army sent two battalions of troops to the capital Nanjing for the handover. Through the nearly eight years after Chinese troops pulled out of Nanjing, the city had been under the governance of Japanese troops and Wang Jingwei's puppet government. Now, the Chinese soldiers returned victorious to Nanjing, carrying new, top-grade weapons. As the majestic troops marched along the streets of Nanjing, the entire city went wild, with excited, laughing crowds craning their necks to get a look.

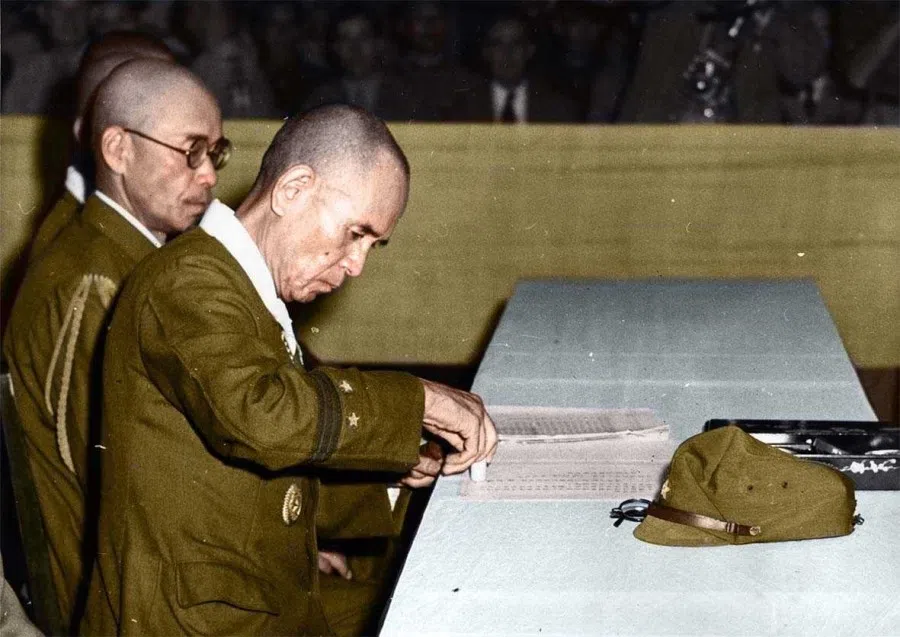

On 9 September, General He led the main commanders inside an assembly hall at the military academy in Nanjing, to accept the instrument of surrender from commander-in-chief of the China Expeditionary Army Yasuji Okamura.

Apart from senior Chinese and Japanese generals, over 1,000 Allied representatives and guests from China and overseas attended the ceremony, which lasted just 15 minutes but became a lasting image in Chinese history. Later, in a radio address to the nation, General He said: "This is a most significant day in Chinese history, the result of eight years of hard fighting."

The repatriation of Japanese POWs and other Japanese

However, after the Japanese surrender, came the real issue of repatriating Japanese POWs and other Japanese in China, who numbered about three million at the time. Since its expansionism during the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895), Japan sent its citizens to its occupied territories for greater convenience in commerce and farming, and to put the Japanese in an advantageous position in these places, so as to attract more Japanese to migrate to overseas colonies. Doing so reduced population pressure within Japan, strengthened the Japanese economy, and boosted social control in its colonies.

The Potsdam Declaration required Japan to revert to its territories before the First Sino-Japanese War, while the Japanese were to be repatriated. At the time of the Japanese surrender, there were over six million Japanese in Taiwan, the Korean peninsula, the southern part of Sakhalin island, Manchuria, major Chinese cities, and Southeast Asia. With the help of US transport vessels, most people returned to Japan by 1949.

The earliest Japanese migrants had lived in the colonies for at least three generations, and they had put out roots there in terms of work, property, and family. According to regulations, each person had a 30 kg limit, and valuable items were strictly controlled.

This meant that many successful middle-income Japanese had to let go of the results of generations of labour and return to their old homes in Japan almost empty-handed, and start from scratch. This was one of the painful costs of Japan's expansionist policy to its people.

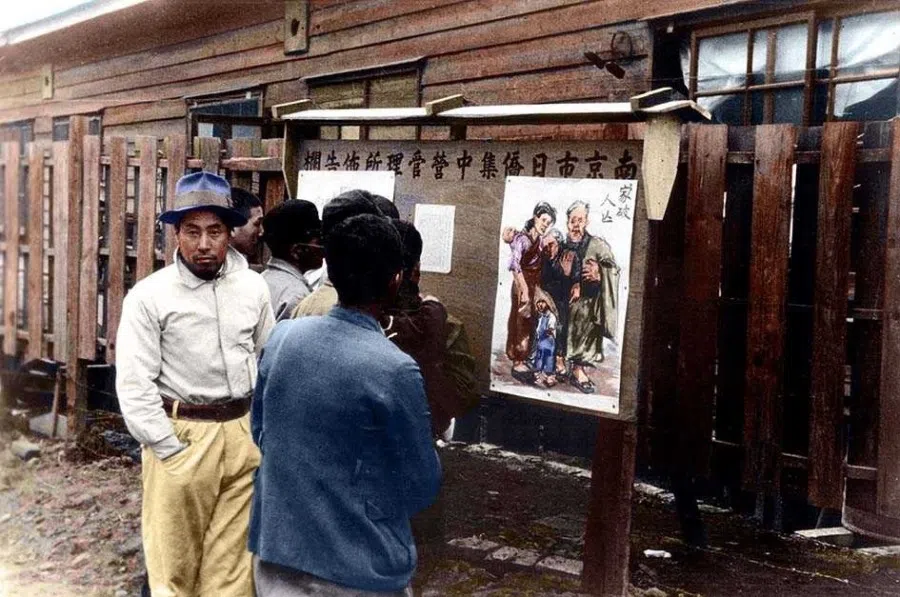

China and the US arranged for Japanese POWs from various cities and villages to gather at the ports, where they would board US transport vessels back to Japan. With China and the US working together to complete the repatriation, most Japanese POWs in China arrived back in Japan by the end of 1946.

A harsh life in Siberia

However, things were more complicated when it came to northeast China. Japan had previously systematically relocated residents of farming villages as "pioneers" to open up farmland in faraway Manchuria. They were provided with weapons and equipment and given some military training, so that they would be a supplementary civilian force for the occupying Japanese troops.

After the Soviet army occupied northeast China, apart from dismantling Japanese heavy industry facilities and shipping them back to the Soviet Union, it also sent about 600,000 Japanese POWs to concentration camps in Siberia. The Soviet Union treated the Japanese POWs as the Japanese army treated Allied POWs - as unpaid labourers who were allowed to die of the cold, or illness, or starvation. An estimated 90,000 Japanese POWs were buried in the frozen expanses of Siberia.

As for the million or so Japanese civilians scattered all over Manchuria, they were left to fend for themselves. These Japanese had been dependent on the Japanese army's aid in terms of military protection, transport and logistics, and agricultural products and sales. From being "class A" residents in Manchuria, they found themselves plunged into a sorry situation. In the face of an ill-disciplined Soviet army and the rapidly escalating war between the armies of the Kuomintang (KMT) and Chinese Communist Party (CCP), their very survival was a struggle.

The "pioneers" included many women, children, and elderly, who made the long journey from the remote China-Russia border to the major cities. Many died of illness or cold along the way. Many women tearfully gave their young children to Chinese farmers; these children came to be known as "war orphans".

Also, many of these Japanese were technical professionals, such as engineers, doctors, and nurses, and the KMT and CCP armies conscripted many Japanese military technicians and medical personnel, who were unexpectedly drawn into the KMT-CCP civil war.

In 1946, through the combined efforts of various parties, about 1.3 million Japanese boarded ships from the main ports in northeast China, bound for Japan. Another 200,000 Japanese were sent back in 1947, after which the repatriation exercise finally ended.

In 1949, the People's Republic of China was established. Order was gradually restored in China, and the last scattered remnants of Japanese POWs and technical personnel retained by the PLA were repatriated through the Red Cross, with tens of thousands sent home between 1952 and 1957. As for the 900 or so Japanese war criminals in Manchuria who were handed over to China by the Soviets, they were also repatriated following re-education.

The Japanese POWs sent to the concentration camps in Siberia by the Soviet army were forced into hard labour amid the frozen plains at -30 degrees Celsius; they had to endure the cold, hunger, and illness, and many lost their lives. The Soviet Union retaliated on the Japanese POWs, forcing them into hard labour in Siberia and only sending them back to Japan in 1956. About 90,000 Japanese POWs did not make it home, but were buried permanently in Siberia.

Magnanimity of Chiang government remembered by the Japanese

While the repatriation of Japanese in China lasted just two to three years, it had a deep impact on the lives of these Japanese. Despite the great harm inflicted on the Chinese during the Japanese occupation, the Chinese government used its limited and valuable resources to send over two million Japanese safely back to Japan, and repeatedly told the Chinese people not to take retaliatory action. There was no doubt that the process affected Japanese sentiments afterwards.

After 1949, many former Japanese officers and soldiers remained grateful to the Chiang Kai-shek government because of the KMT government's magnanimous policy, while the Japanese who served in the People's Liberation Army (PLA) became a key force in promoting exchanges between the people of China and Japan.

In 1972, China-Japan relations returned to normal, and both countries began to address the legacy of history, including looking into the "war orphans" left behind by the Japanese who fled northeast China. The Japanese government recognised these people as Japanese citizens, and sought to locate them over the next 20 years, arranging for them and their next generation to return to Japan and settle down.

Over the next few decades, Japan produced many literary, TV and cinematic works featuring the Japanese who lived in northeast China and their personal experiences of being set adrift after the war, which became an important historical memory for the Japanese people.

In 2015, Japanese station TBS produced a TV special called Red Cross: Onnatachi no Akagami (literally Red Cross: Women's Draft), about a Japanese woman who goes to Manchuria to be a nurse and is drafted into the PLA after the war along with other Japanese doctors and medical workers, and then is sent back safely to Japan. This extraordinary life story is full of the travails of war, which helped to rebuild lives and psyches of peace, amid the conflict and tolerance of the people of China and Japan. In a certain sense, such a realisation of history is the highest form of humanity.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)