[Photos] From Nanjing streets to family memories: A historical photo collector reflects on Chinese New Year

Through rare photos of Beiping and Nanjing, Taiwanese historical photo collector Hsu Chung-mao recalls bustling temple fairs, lanterns and family traditions, reflecting on the enduring spirit of Chinese New Year.

(All photos courtesy of Hsu Chung-mao.)

With the Spring Festival around the corner, coupled with China’s growing national strength, the world has its eyes on traditional Chinese culture. In recent years, it has even become fashionable for world leaders to send Chinese New Year greetings and auspicious wishes to Chinese communities worldwide, sometimes deliberately wearing Chinese-style padded jackets.

So what does the traditional Chinese New Year actually look like? Let me give some examples of Spring Festival activities in Nanjing and Beiping (Beijing) during the Republican era. The photographs in this article are specimens of traditional Chinese New Year celebrations. Like the traditional festivals of every culture, these celebrations are not just about activities, but also about food, theatrical performances, auspicious symbols and the transmission of values.

Because of this focus on family values, rituals of honouring ancestors and remembering one’s roots naturally form the core of the belief system.

Temples and river banks come to life

In the West, the most important festival is Christmas, rooted in the Christian belief in the birth of Jesus, symbolising compassion, joy and hope, and emphasising family reunion. Chinese New Year, by contrast, originated in agrarian society during the winter fallow season. It also includes ancestor worship and rituals honouring deities, but because it is not based on monotheism, religion is not the dominant element. Instead, the emphasis is on family reunion: no matter how far family members live — even overseas — they are expected to come home. Because of this focus on family values, rituals of honouring ancestors and remembering one’s roots naturally form the core of the belief system.

I have collected photographs from various periods of Chinese history for many years, and my collection of Spring Festival images from the Republican era is particularly rich. In this article, I introduce the Spring Festival activities in Nanjing and Beiping, two cities regarded as the southern and northern capitals of China.

Nanjing was the capital of the Republic of China and the centre of major political, governmental and military figures and activities, so its New Year celebrations were widely reported. In fact, Nanjing is also an ancient capital of six dynasties, rich in historic sites, tales of the rise and fall of empires, and legends of scholars and beauties celebrated through the ages. The lively Spring Festival, combined with this deep historical heritage, gives the city a distinctive and powerful charm.

Spring Festival activities in Nanjing were mainly concentrated in the area around Confucius Temple (夫子庙), close to the former Jiangnan Examination Hall, which once held some 20,000 cubicles for candidates who came every year from surrounding provinces to sit for the imperial examinations, bringing thriving business to inns, restaurants, theatres and even brothels in the district.

This area is also near the banks of the Qinhuai River, with a unique atmosphere of its own. During the Republican period, although the imperial examination system had been abolished, the bustling streets remained much the same. During the Spring Festival, this became the liveliest part of Nanjing.

Temple fairs ran from the eve to the 15th day of Chinese New Year, with stalls offering traditional snacks such as sweet lotus root porridge, tofu pudding and cha san (茶馓, a type of deep fried dough snack); handicrafts such as paper cuttings, silk flowers and wood carvings; and New Year prints and couplets.

Traditional snacks and handicrafts

Along the banks of the Qinhuai River near the Confucius Temple hung all kinds of colourful lanterns — in the shape of lotus, rabbit, palace and more — forming the famous Qinhuai Lantern Fair. Families took their children to the fair, buying handmade lanterns or solving lantern riddles. Temple fairs ran from the eve to the 15th day of Chinese New Year, with stalls offering traditional snacks such as sweet lotus root porridge, tofu pudding and cha san (茶馓, a type of deep fried dough snack); handicrafts such as paper cuttings, silk flowers and wood carvings; and New Year prints and couplets.

Painted pleasure boats cruised the river, red lanterns hanging from their bows, as visitors admired the lights on the banks and listened to folk tunes, in a unique scene that writer Zhu Ziqing described as “the sound of oars amid lantern reflections” (桨声灯影).

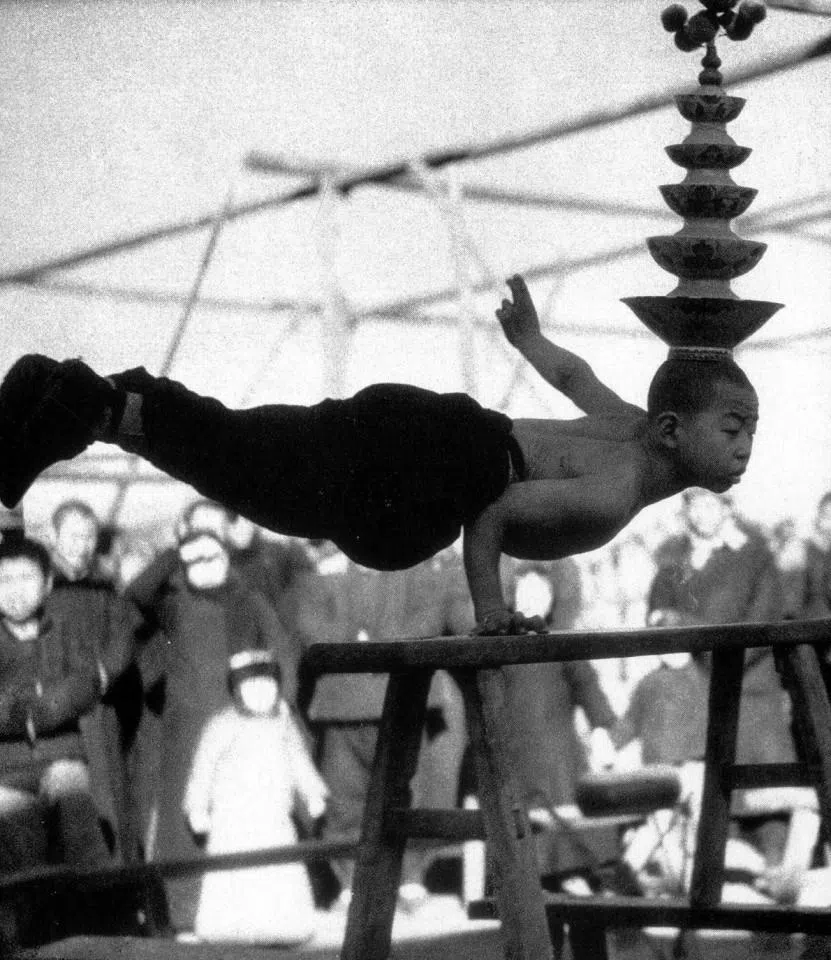

Opera and acrobatic performances were also common. Open-air shows were frequently staged at the Confucius Temple square and in teahouses such as Kuiguang Pavilion, featuring Nanjing folk ballads, Pingtan storytelling, shadow puppetry, as well as acrobatics and acts involving monkeys, drawing crowds of onlookers.

Praying for blessings during the New Year was another important tradition. People would cross Wende Bridge at the Confucius Temple on the night of the 15th day of Chinese New Year to “walk away a hundred ailments”, or visit the former Jiangnan Examination Hall to touch stone carvings, symbolising academic success.

As for traditional food, well-known teahouses like Yonghe Garden and Qifang Pavilion offered special New Year dim sum sets, featuring spring rolls, osmanthus-flavoured taro dumplings, five-spice eggs and other seasonal treats.

Nearby temples, such as the ancient Jiming Temple, were also popular places to offer incense during the New Year. As for traditional food, well-known teahouses like Yonghe Garden and Qifang Pavilion offered special New Year dim sum sets, featuring spring rolls, osmanthus-flavoured taro dumplings, five-spice eggs and other seasonal treats. Street vendors also sold freshly made candied hawthorn skewers and glutinous rice-stuffed lotus root.

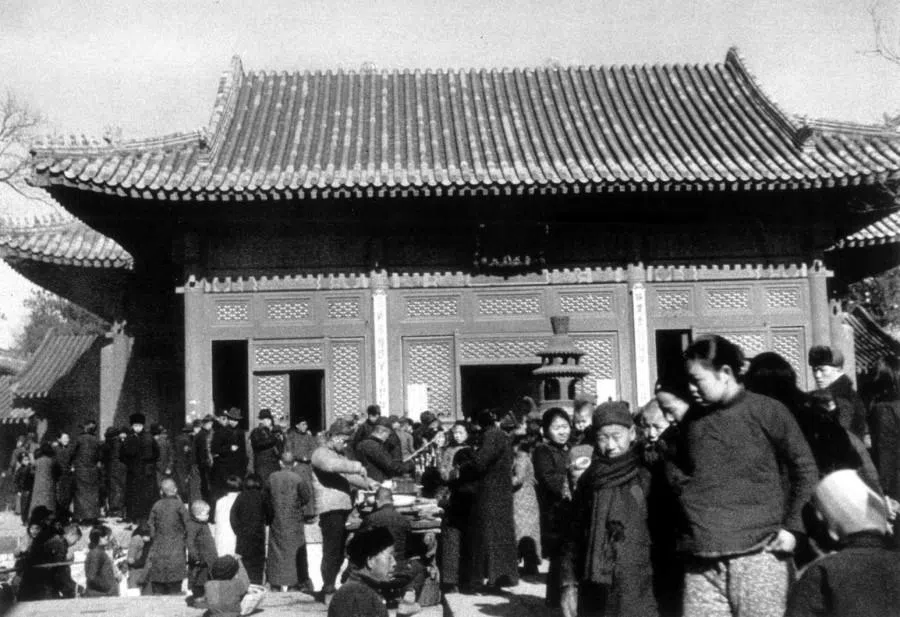

Here I present bustling scenes from the Qinhuai Lantern Fair in 1958. These are original historical photographs that I have owned for 30 years, and are extremely precious. Although they date from the later years of the Republican era, everyday urban life had not changed much, and people still celebrated the New Year with joy.

... a visit to the Changdian temple fair (逛厂甸) was considered an essential New Year activity.

Blessing rituals and symbolic snacks

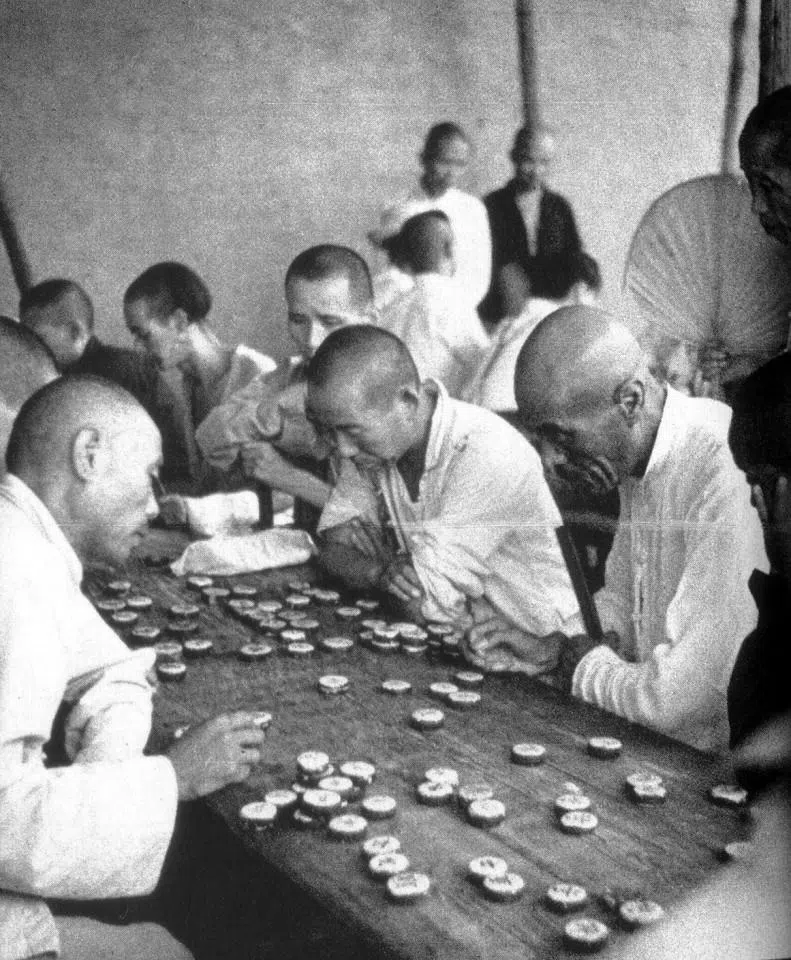

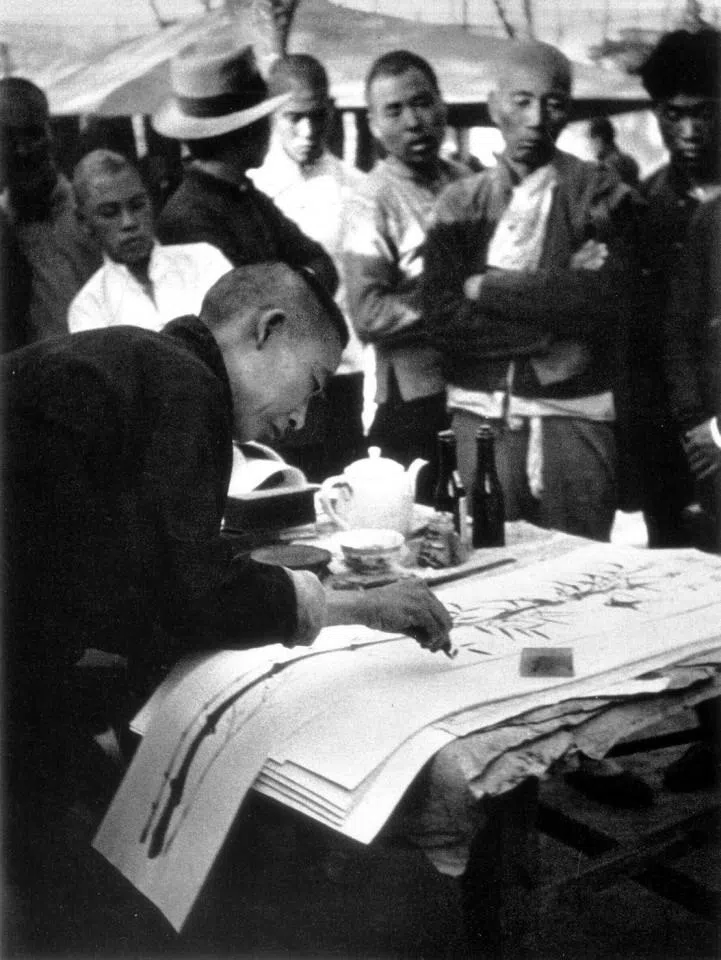

As for Beiping, its New Year celebrations were also closely linked to temple fairs. The Liulichang area hosted the grandest open-air temple fair in Republican-era Beiping. From the first to the 15th day of the lunar month, there was an array of stalls selling antiques, calligraphy and paintings, copybooks, windmills and candied hawthorns, and scholars and ordinary citizens alike came in a steady stream, while a visit to the Changdian temple fair (逛厂甸) was considered an essential New Year activity.

Another major event was the Baiyunguan temple fair, a Taoist sacred site that reached its climax during the Yanjiu Festival on the 19th day of the first lunar month, commemorating the birth anniversary of immortal Qiu Chuji, when it was believed that he would descend to the mortal world.

From the first day of the New Year, crowds surged in, especially for blessing rituals such as “touching the stone monkey” to ward against illness and evil, and tossing coins through an opening or a model of an old bronze coin for wealth and good luck. Worshippers jostled shoulder to shoulder, while acrobats and food vendors stretched for miles. Other temples, such as Dongyue Temple, Huguo Temple and Longfu Temple, were also bustling with incense offerings, opera performances and throngs of shoppers.

In midwinter, when the lakes froze over, the Shichahai ice rink became a popular ground for the masses to have fun. Ice sledding and skating was common, while temporary tea stalls along the banks sold hot food, amid a blend of laughter and chatter, gongs and drums.

As for traditional food, Beiping’s Spring Festival cuisine was especially famous. Rice cakes symbolised rising higher each year, while northern-style dumplings, shaped like silver ingots, represented wealth and treasure. Coins were sometimes hidden inside the fillings, and whoever found one was believed to have good luck in the coming year.

In Beiping, by contrast, activities centred on a network of temple fairs, dispersed across multiple religious and commercial districts.

Elegant displays in the south, bold forms in the north

Finally, although Spring Festival activities in both Nanjing and Beiping centred on temple fairs, there were notable regional differences. In Nanjing, the celebrations revolved around the Qinhuai River and Confucius Temple district in the southern part of the city, a combined spectacle of land and water. The Confucius Temple integrated examination culture, popular entertainment, and food from long-established eateries, while night cruises on Qinhuai lantern boats highlighted the gentle elegance of the Jiangnan water towns.

In Beiping, by contrast, activities centred on a network of temple fairs, dispersed across multiple religious and commercial districts. Changdian was a large open-air cultural market known for rare books, antiques, windmills and candied hawthorns; Baiyun Temple focused on Taoist rituals and blessing ceremonies; Longfu Temple and Huguo Temple focused more on daily necessities and snacks, catering to everyday urban life.

Nanjing’s Spring Festival decorations featured Qinhuai lanterns made of fine bamboo and silk gauze, often in lively shapes such as lotus flowers and rabbits, with lantern light reflecting on rippling water. Shops displayed traditional signboards, and houses by the river hung colourful lanterns, projecting refinement and grace.

Beiping’s decorations, influenced by the grand palace aesthetics of the Ming and Qing dynasties, favoured palace-style lanterns and gauze lanterns with bold forms and vivid colours. Temple fair stalls were often draped in red and yellow cloth, set against snowy backdrops for striking contrast.

Nanjing’s Spring Festival resembled a flowing Jiangnan ink painting, where the refined ease of urban society unfolded amid the sound of oars, and lanterns reflected on the Qinhuai River.

Celebrating Chinese New Year no matter where you are

Overall, the Spring Festival celebrations in Nanjing and Beiping were different, a reflection of the broader contrast between southern and northern China. Nanjing’s Spring Festival resembled a flowing Jiangnan ink painting, where the refined ease of urban society unfolded amid the sound of oars, and lanterns reflected on the Qinhuai River. Beiping’s Spring Festival, by contrast, was like a richly coloured scroll, carrying forward the inclusiveness and gravitas of the imperial capital through the smoke and bustle of temple fairs.

At their core, these differences reflected the contrasting civilisations of loess land and water towns, together forming a diverse picture of urban New Year customs in Republican-era China.

In looking at the Spring Festival activities of Nanjing and Beiping during the Republican period, we are in fact seeing how ethnic Chinese or Chinese around the world celebrate Chinese New Year. Today, in an industrial and commercial society, Spring Festival activities across China no longer resemble those of an agrarian age; many people even take the opportunity to travel abroad during the holidays, avoiding crowded local shopping streets. Even so, many regions still strive to preserve traditional celebrations, and many people continue to take part, albeit in less varied forms and for a shorter period.

In Hong Kong and Taiwan, where it is even more industrialised and commercialised, the festive atmosphere has in fact declined over the years. Overseas ethnic Chinese communities, living within multicultural societies, often become cultural highlights for local media coverage, turning the Spring Festival into a global cultural symbol and, with China’s growing strength, a symbol of Chinese culture itself.

... after I married and had children, my wife Maggie — who comes from Penang, Malaysia, where Chinese communities maintain strong Spring Festival traditions — brought that festive spirit into our home.

As for my family, influenced in the past by elders’ Christian beliefs, we once deliberately toned down the Spring Festival atmosphere. However, after I married and had children, my wife Maggie — who comes from Penang, Malaysia, where Chinese communities maintain strong Spring Festival traditions — brought that festive spirit into our home.

When our children were young, we made an effort to celebrate the New Year, putting up decorations so the whole family could feel the festive mood. After my parents passed away and only the four of us remained at home, we began travelling abroad during the Spring Festival. Even so, our children still take turns writing Spring Festival couplets and pasting them on the door. Even when overseas, on the first day of the Chinese New Year, we would take photos with red packets in hand, preserving our Chinese traditions.