[Big read] Online Chinatowns: Connecting or isolating overseas Chinese?

Chinese social media platforms are seeing the rise of online Chinatowns — online communities that bridge the geographic gap between Chinese nationals living around the world and help overseas Chinese to connect with each other. Lianhe Zaobao senior correspondent Chen Jing discusses how this modern phenomenon is making an impact.

“If you enjoyed our performance tonight, please help us spread the word by leaving a review on Xiaohongshu!”

In August, Shanghainese stand-up comedian, Men Qiang, gave a solo performance in Singapore. Other than the fact that it was held at the Capitol Theatre Singapore, the event was not that much different from his Shanghai shows —everyone from the audience to the crew spoke China-accented Mandarin, and payments for merchandise were limited to cash, WeChat Pay and Alipay.

After the show, the organiser encouraged the audience to help them publicise the tour by posting on Xiaohongshu, and to join their WeChat group for more performance-related information.

In the “online Chinatowns” of Chinese social media platforms like Douyin, Xiaohongshu, WeChat and Weibo, millions of Chinese nationals overseas are exchanging information, making friends and organising activities.

Though there was close to zero publicity of the show on Singapore’s mainstream media, there were no empty seats in the venue, which can accommodate close to a thousand.

‘Online Chinatowns’

Liu Mei (pseudonym), a Shanghainese working in Singapore, told Lianhe Zaobao that she learned about the performance through multiple channels: Douyin, a Xiaohongshu influencer and a friend on WeChat. “I bought tickets with my friends,” she added.

In the “online Chinatowns” of Chinese social media platforms like Douyin, Xiaohongshu, WeChat and Weibo, millions of Chinese nationals overseas are exchanging information, making friends and organising activities.

Before she came to Singapore to pursue her postgraduate studies in 2021, Han Xinnan from Jilin turned to Xiaohongshu for immigration advice. While her school provided information about the standard process, she decided to play it safe by consulting Xiaohongshu for real-time updates and personal experiences shared by other users.

Paying it forward, Han now actively contributes her own experiences, covering everything from food and entertainment to personal reflections, food poisoning, and even eye surgery. She views Xiaohongshu as an encyclopedic mutual aid platform. “Xiaohongshu unites overseas Chinese,” she explains. “You can find out anything from today’s sunset time in Paris to the worst restaurant in Singapore.”

With the advent of social media platforms, immigrant associations have moved online, transcending the constraints of geography and blood relations to create a much greater impact.

Forming united communities amid China’s rise

In a Lianhe Zaobao interview, Assistant Professor Stefanie Kam from the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies (IDSS) at the Nanyang Technological University (NTU) S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) highlighted how overseas Chinese communities utilise digital platforms to create support networks, assisting new immigrants and maintaining strong ties to their homeland. “The strong familial connection and Confucian ethic internalised by mainland Chinese also makes them perhaps some of the most united communities in the world today regardless of where they are,” she explained.

Immigrants with the same roots banding together in mutual support is nothing new. In earlier times, Chinese immigrants established clan associations in Singapore to serve as platforms for mutual aid and information exchange. With the advent of social media platforms, immigrant associations have moved online, transcending the constraints of geography and blood relations to create a much greater impact.

Kam said that while in the past most Chinese immigrants to Southeast Asia were poor and lowly skilled, Chinese immigrants today have greater capital and mobility, in addition to being highly skilled, talented and well-connected. “The role of the Chinese diaspora has been pushed to an even more prominent position with the Chinese Dream and Belt and Road Initiative,” she added.

Online Chinatowns inhibiting assimilation?

While the plethora of Chinese resources helps overseas Chinese navigate challenges abroad, over-reliance on them can create an isolating bubble, leading to cultural and social conflicts with host countries.

In October 2023, a Chinese influencer with 250,000 Douyin followers was fined and jailed before being repatriated from Singapore for verbally abusing nurses at a hospital and hurling vulgarities at police officers. The case sparked discussions on the differences between Singaporean and Chinese society within Chinese circles. While some believed the influencer’s punishment was justified for breaking local laws, her online supporters accused Singapore of discrimination against Chinese people.

Liu from Shanghai feels that while the recent influx of Chinese companies and talent into Singapore has invigorated the local economy and job market, cultural clashes are inevitable. Given the larger size of the overseas Chinese community compared to other groups, increased scrutiny of such incidents is unsurprising.

Liu pointed out that her hometown of Shanghai is as cosmopolitan as Singapore and said, “There are bound to be cultural differences, and the fusion of foreign and local cultures can result in new cultures. I see this as the norm.”

“... in addition to keeping in touch with their own communities, immigrants should also join local platforms and adapt to their adopted countries’ societies and cultures.” — Associate Professor Selina Ho, LKYSPP

Academic: maintaining existing ties important, but so is assimilation

During our interview, Selina Ho, an associate professor in international affairs and co-director of the Centre on Asia and Globalisation at the National University of Singapore (NUS) Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy (LKYSPP), highlighted that it is normal for immigrants to keep in touch with their communities and motherland. “However, in addition to keeping in touch with their own communities, immigrants should also join local platforms and adapt to their adopted countries’ societies and cultures. This would facilitate their integration to local communities and enable them to truly understand the new environments they live in,” she added.

After working in Singapore for two years, Han from Jilin found herself using Instagram and Facebook more often. Owing to her interest in religion, she has also joined several related Facebook groups. “I can see the ongoing events at various temples, regional differences in religion, it is interesting,” she said.

At the same time, she has also started reading the news from mainstream Singaporean media and English media platforms like the BBC. She shared, “Whenever I come across a Lianhe Zaobao newsfeed on Facebook, I’d click on the comments section to see what people are saying and listen to different views.”

Social media pushing foreign agendas in host countries?

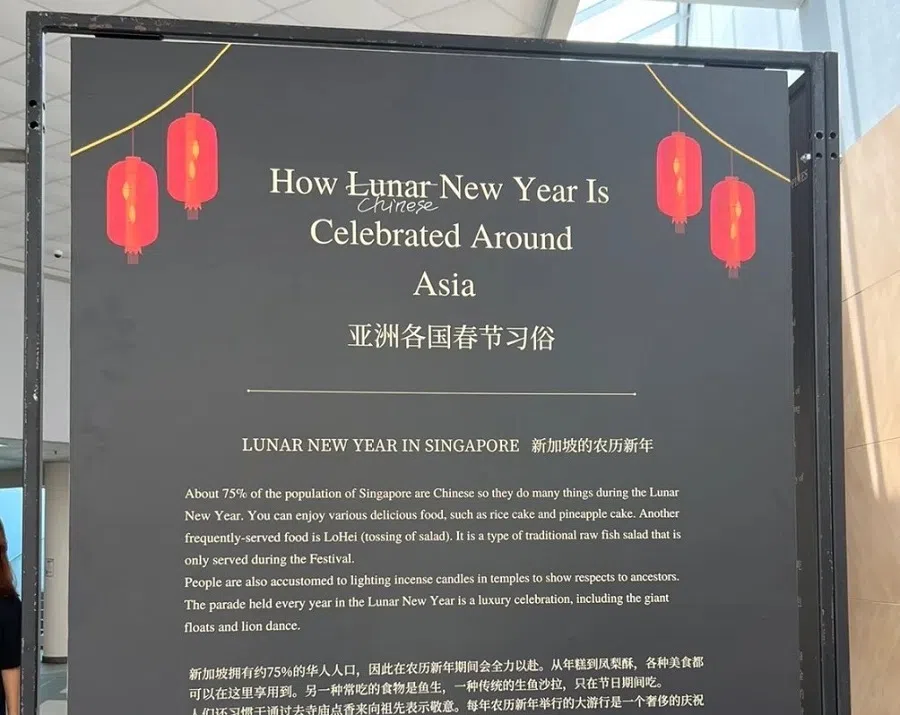

In January 2023, an NTU campus event display board containing information on Lunar New Year customs in various Asian countries was vandalised — the perpetrator had replaced the word “Lunar” with “Chinese”.

At the same time, some Chinese students in NTU took to Xiaohongshu to voice their displeasure at school authorities’ position that student organisations use “Lunar New Year” instead of “Chinese New Year”. They argued that it showed a lack of respect towards Chinese students.

In the face of public controversy, an NTU spokesperson responded to media enquiries by pointing out that Lunar New Year is not an exclusively Chinese celebration — the university also has students and staff from countries like South Korea and Vietnam who also celebrate Lunar New Year. Therefore, in the spirit of diversity and inclusivity, NTU decided to use “Lunar New Year” instead of “Chinese New Year”

With the aid of social media platforms, new immigrant social networks may pursue the agenda of their country of origin abroad, resulting in social implications for host countries.

All along, the terms “Chinese New Year” and “Lunar New Year” have been used interchangeably locally. But Chinese netizens arguing against the use of “Lunar New Year” felt that it would allow other countries to appropriate the traditional Chinese festival for their own. “After this they might also say that the Spring Festival originated from Vietnam and South Korea,” the netizens said.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, more Chinese migrated to Singapore, amplifying its community influence. With the aid of social media platforms, new immigrant social networks may pursue the agenda of their country of origin abroad, resulting in social implications for host countries.

During the pandemic, some new media outlets in Singapore targeting recent new Chinese immigrants published articles and social media posts promoting Chinese-made Covid-19 vaccines over the readily available Pfizer vaccine. This sparked considerable discussion within immigrant communities and even generated public pressure.

Academic: Singapore government clear about potential impact of social media

Dylan Loh, an assistant professor at the Public Policy and Global Affairs Division of NTU, expressed confidence that the government understands the media landscape and potential “echo chamber” effects. He noted that preferring certain media outlets isn’t unique to Chinese nationals. “Just as British expats might exclusively consume The Guardian and BBC,” he explained, “there is nothing surprising about Chinese nationals doing the same.”

Nonetheless, Loh added that concern would be warranted if foreign actors spread disinformation or pressured local media to suppress sensitive information.

At the FutureChina Dialogue held in Singapore this March, Minister of the International Department of the Communist Party of China Liu Jianchao said that while it is human nature for ethnic Chinese in Southeast Asia to be emotionally attached to their ancestral country and culture, such ties should not affect national identities. He added, “You should pledge your allegiance to the country of your citizenship.”

Liu also differentiated between ethnic Chinese and Chinese nationals overseas, or huaqiao. He emphasised that ethnic Chinese are not Chinese nationals, while huaqiao continue to hold Chinese citizenship. He also said the Chinese government requests that its citizens living abroad abide by local laws, and maintain friendly relations with the locals to fulfil their roles as bridges and links.

NTU’s Kam opined that while the Chinese diaspora is increasingly seen as an economic resource and political agent for China, such communities in Singapore appear to be pragmatic self-help support networks formed at the grassroots.

She is also of the view that there needs to be further research on this trend in the Chinese diaspora by scholars of the “global China” issue to “understand more broadly China’s transformation, its place in Asia, and the potential for overseas Chinese communities to inflect national policy frameworks or ideologies in their host countries”.

To Chen, her involvement in group-buying is the main channel for her to grow her contacts and obtain information.

Study mamas who double as group-buy organisers

42-year-old Chen Yanting is a “study mama” who is in Singapore to look after her two children who are studying here. At the same time, she organises group buying for nearly 300 members.

Three years ago, Chen arrived in Singapore from Ningbo, Zhejiang. Extroverted by nature, she quickly joined a WeChat group-buying community in her neighbourhood at the recommendation of her neighbour. Subsequently, she took over as the organiser to aggregate weekly fresh food and fruit orders from her neighbours. Last year, she was even invited in her capacity as a group-buy organiser to attend the gong-sounding ceremony for WeBuy’s public listing.

To Chen, her involvement in group-buying is the main channel for her to grow her contacts and obtain information. She recalled the alienness of it all when she first got here, but through group- buying she interacted more with her neighbours and began to understand more about education, livelihood, and immigration policies in Singapore.

“For instance, my ex-neighbour’s daughter successfully applied for permanent residency, so I asked her how she did it. Or when I wanted to find a math tutor for my son, I managed to get my former group-buying organiser’s child who was studying at the National University of Singapore to help. If I were not involved in group-buying, I wouldn’t have access to all these resources,” she explained.

Group-buying users are mostly new immigrants from China; a number of them are study mamas like Chen, which explains why she feels as though she is still back in China and “found a sense of security very quickly”.

At the same time, Chen is unable to tolerate people’s intense parenting styles (鸡娃 jiwa, lit. giving children chicken blood) and “involution” (卷 juan, referring to various forms of inward spiral, regression or stagnation) that permeate study mama circles.

She said candidly, “I’ve seen children in primary three or four who attend three tuition classes for one subject, at the same time they are involved in all sorts of competition to qualify for direct school admission. I feel there is no need to be so involuted anymore since we have left China, moreover this would make the locals dislike us.”

Chen also wishes to befriend non-Chinese Singaporeans, but owing to language constraints she finds herself unable to interact meaningfully with them. So, she has set a target for herself to improve her English so that like her son, she is able to make new friends from different countries.

From new immigrant to Xiaohongshu influencer

“How much does it cost to make a bowl of malatang in Singapore?”, “How difficult is it to prepare a meal of jidan guanbing (egg pancakes) in Singapore?” These topics are among some of the experiences Shaanxi-born Wu Tao has shared on Xiaohongshu, Douyin and Kuaishou. Through posting his experiences of reproducing native Chinese food in Singapore, he has become a budding influencer with around 10,000 followers within a year on each platform respectively.

Last year, the 28-year-old started using his free time to produce videos on food and his everyday life. To his surprise, a video he posted about a doctor’s visit was promoted by Xiaohongshu, and he subsequently gained several hundred new followers. During our interview, Wu expressed his incredulity at his newfound fame — “It somehow went viral.”

From then on, Wu started managing his social media profiles seriously. Each week, he uploads at least two self-made videos, one on how to use local ingredients to make a Chinese dish, and another on what he does on his rest days.

Other than Chinese social media platforms, Wu also uploads the same videos onto foreign social media platforms like TikTok and Instagram. But he found that they generated the most subscriber activity, comments, and interactions on Xiaohongshu and Douyin. Backend data analytics from Xiaohongshu indicate that more than 60% of his followers are female and most of them are Chinese nationals residing in Singapore.

Female consumers form the bulk of Xiaohongshu users. In 2022, there were more than 550,000 active users of the platform in Singapore. In the last couple of years, it has become a platform that some businesses actively cultivate. At the same time, there are many local organisations offering Xiaohongshu account management and influencer training services.

After becoming an influencer, Wu started receiving collaboration offers for him to promote local restaurants and healthcare organisations to Chinese consumers. As an employee of a dessert business, he hopes to use the opportunity to move towards his goal of starting his own restaurant.

After working here for seven years, it has become second nature for Wu to use the Singaporean Chinese terms for “drinking straw” (Singapore’s shuicao vs China’s xiguan) and “key” (Singapore’s suoshi vs China’s yaoshi). Yet the food blogger also admitted that he mainly opts for familiar-tasting noodle or barbecue dishes when he eats out, and has yet to try Hainanese chicken rice.

To attract local fans, Wu is considering making local dishes. He said, “Maybe I’ll start with minced pork noodles since it’s also a noodle dish, so it should be easier to master.”

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “小红书微信抖音 中国社媒串联网络唐人街”.