India's choice: Pro-US, pro-China or stay autonomous?

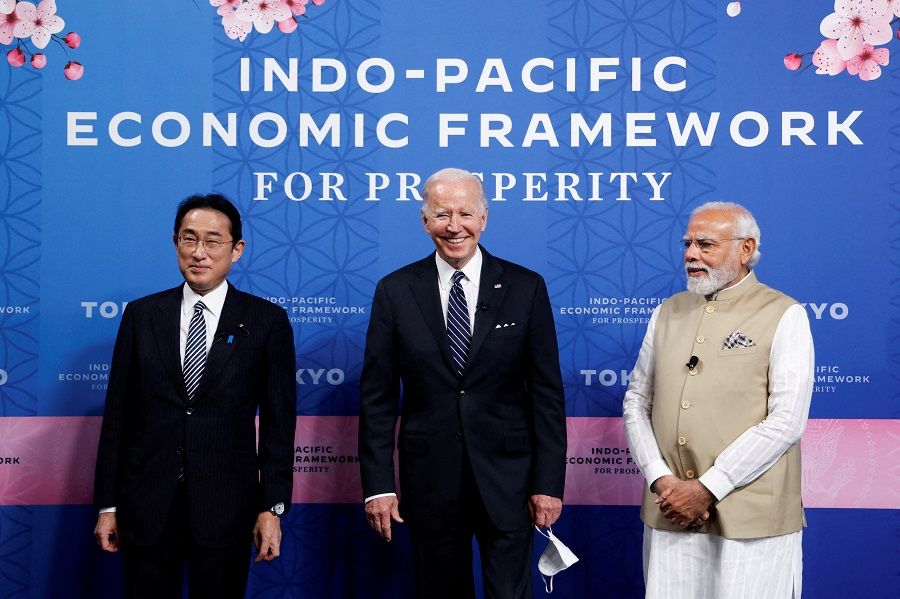

The risk of a US-China showdown in the Indo-Pacific is in sharp focus following the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore on 10-12 June. Three recent moves - The US-led Quad and Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF), and China's Global Security Initiative (GSI) - will be tested in this region.

Among the players who matter to both the US and China, India can "tilt" towards either and play the role of a "swing state", so to speak, in mutual interest. Staying autonomous, with or without costs, is an option, too, for Delhi.

The context for India's potential role

China has the globally recognised calling card of a big trading nation. Benefiting from its capabilities to manufacture goods at home and build infrastructure abroad, Beijing has so far gained much. But this conventional model is beginning to falter in the new global trend towards high technology in the economic and military domains.

On the military side, Chinese President Xi Jinping has launched the GSI, articulating the need to "uphold the principle of indivisible security, build a balanced, effective and sustainable security architecture, and oppose the pursuit of one's own security at the cost of others' security". This is a sequel to his Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and Global Development Initiative (GDI).

In response, US President Joe Biden seeks to deploy his country's high-tech skills to woo partners and confound China. The aspirational IPEF, a non-conventional economic union, is a sequel to the Quad which houses the US, Japan, India and Australia in a "soft security" forum focused on "space-based maritime domain awareness", with an eye on China.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi is aware of the potentiality of the Quad and the IPEF. However, he also cannot dismiss the value of the BRICS, a compact inter-continental forum of emerging markets comprising Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa.

From China's perspective, the Quad is a "clique" while the BRICS is more like a "circle of friends". Another "circle of friends", in which India is with China, is the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), a Sino-Russian initiative for primarily non-traditional security.

Prospects of swinging to either side

Biden and his Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin have respectively said that Washington is "expanding cooperation" and "weaving closer ties" with India in the emerging technologies and "new defence domains". America has already ensured the international recognition of Delhi as a responsible power, although its atomic arsenal remains outside the ambit of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). Furthermore, the robust people-to-people ties between India and the US and their growing economic relations could induce Delhi to "swing" towards Washington.

Any such development might suit both sides due to the current uncertainties in China's relations with both India and the US. Their shared perception of China's composite national power as a challenge in the Indo-Pacific is the strategic glue. The civil and military benefits that India might receive from the US could also serve the latter's objective of checkmating China.

The conditional US desire to avoid a Cold War or hot war with China today may even incentivise a reconciliation between these two rivals, forcing Delhi to stay autonomous.

However, it will not be an easy bargain for both Delhi and Washington. The decades-long China-India boundary dispute is compounded by their power imbalance. Yet, India is also not part of the nucleus of the US-led military alliances within and outside the Quad.

Besides this limiting factor, Delhi remains wary of a possible Sino-American conciliation now as in 1971. The military challenge for Washington from the anti-China Soviet Union in 1971 pales in comparison with Beijing's all-pervasive competition with the US in 2022. The conditional US desire to avoid a Cold War or hot war with China today may even incentivise a reconciliation between these two rivals, forcing Delhi to stay autonomous.

Nonetheless, Delhi cannot ignore US high-tech military prowess for security collaboration while the relevant Russia-India cooperation might only recede. In stark contrast, China projects itself as a beacon of economic opportunities for India too, an aspect that the latter does not discount altogether. However, the baseline for India's economic "swing" towards China is a resolution of the Sino-Indian boundary dispute on the basis of "mutual and equal security". This principle has remained on paper despite many rounds of talks.

India has clarified that "the final contours" of the IPEF would emerge only after discussions among its members, especially the Quad. This might indicate that India has not yet cast its lot fully with the US in the economic domain.

Strategic quotient of IPEF

India seems to have perceived Biden's IPEF as an opportunity for a potential economic "swing" towards the US in the emerging high-tech areas. India had earlier excluded itself from the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) following the collapse of asymmetric Sino-Indian negotiations under the canopy of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Delhi's latest move to ride Biden's bandwagon (as critics view the IPEF) is therefore conspicuous.

India has clarified that "the final contours" of the IPEF would emerge only after discussions among its members, especially the Quad. This might indicate that India has not yet cast its lot fully with the US in the economic domain. For India, though, unlike China, the US is no "rival" to be extremely wary of. And it seems that the Chinese are not too worried. A critical view among the Chinese strategic community is that "India's ... 'never make, always break' record in multilateral cooperation" could delay the IPEF and benefit China.

Furthermore, Wang Huiyao, president of the Centre for China & Globalization, says that Sino-American efforts could still "amplify the green benefits of the IPEF and the BRI". Nonetheless, the economic dimension of the "Indo-Pacific" has largely been banished from Beijing's lexicon.

IPEF's future will be determined by the longevity of US strengths in key strategic domains and its willingness to share the same with allies, partners and others.

BRICS as building block for a new order

While IPEF is the new talking point, China, the current rotating chair of the BRICS, is keen to expand it to include some developing countries. At the BRICS foreign ministers' video conference, hosted by China on 19 May 2022, it was agreed that expansion could take place through discussion-based consensus among the members.

India insists, however, on a prudent expansion so that the group does not lose its relevance as an economic Permanent Five (P5) of the global south.

Strategically different, though, is the membership expansion of the New Development Bank (NDB). Following discussions at the BRICS summit hosted by India in 2012, this exclusive bank for emerging markets and developing countries was set up in Beijing.

For India, the BRICS, an economic group, and the SCO, an anti-terror network, can also be relevant to an alternative new world order that Washington might continue to lead.

The Chinese and Indian economies are prominent in the BRICS forum and the NDB. Furthermore, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), proposed by China and backed by India, is propagated as a future-focused institution in this pivotal sector. Beijing and Delhi have by and large cooperated in both banks.

For China, these two banks and the BRICS as well as the SCO can serve as building blocks to reshape the world order after the ongoing Ukraine crisis. For India, the BRICS, an economic group, and the SCO, an anti-terror network, can also be relevant to an alternative new world order that Washington might continue to lead.

Towards 21st century security governance

Security is the foundation of any new order too. An official annotation of China's GSI is that it advocates "indivisible security", meaning the equal security of all countries. They could ensure such universality by "following ... a path of mutual respect and peaceful coexistence".

Despite such high-minded pronouncements, China is suspected to have negotiated strategic access to Djibouti, Hambantota and the Solomon Islands in the Indo-Pacific. Having recently signed a "security framework agreement" with the Solomon Islands Beijing was keen to seek a regional accord with all Pacific Islands. However, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi explained on 3 June 2022 that the objective is "to build roads and bridges ... not to station troops or build military bases".

For Delhi, the credible choice of either strategic autonomy or the role of a "swing state" in support of the future global leader might hold the key.

Globally, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is increasingly paralysed due to the strategic polarisation between the US-led West and the China-Russia partnership.

The P5 of the UNSC - China, France, Russia, the UK and the US - hold the right to veto. Their entitlement is among the subjects for UN reforms now. Indeed, on 26 April 2022, the UN General Assembly (UNGA) empowered itself to review every future veto by any member of the P5. Welcoming this initiative to "rein in the exercise of veto", veteran Indian diplomat Prabhat P Shukla called for a review of "anomalies" at the UN in today's geopolitical context.

One of these "anomalies" is the continued exclusion of India from the global high table in the UNSC. As a British colony when the UN was founded, India was not considered for permanent membership in the UNSC. China, too, was at first represented by the "Republic of China", not the People's Republic of China (PRC), now universally known as China. But unlike China, India is still biding its time while pleading for a new multipolar order. For Delhi, the credible choice of either strategic autonomy or the role of a "swing state" in support of the future global leader might hold the key.

Related: Shangri-La Dialogue 2022: A tougher diplomatic battle for China? | US-ASEAN summit: Washington still has an uphill climb | Global Security Initiative - China's solution to international security? | Will China-Solomon Islands security cooperation bring new tensions to the South Pacific? | Quad now centrepiece in India's China strategy | AUKUS and Quad do not solve India's regional security problems