From ambiguity to endorsement: China’s backing of Myanmar’s junta

For the past few years, China has maintained strategic ambiguity in Myanmar, engaging with both the military junta and ethnic armed groups. Now, with its closure of border trade points and its open endorsement of the junta, China’s strategy has shifted. Indian academic Rishi Gupta examines the key motivating factors.

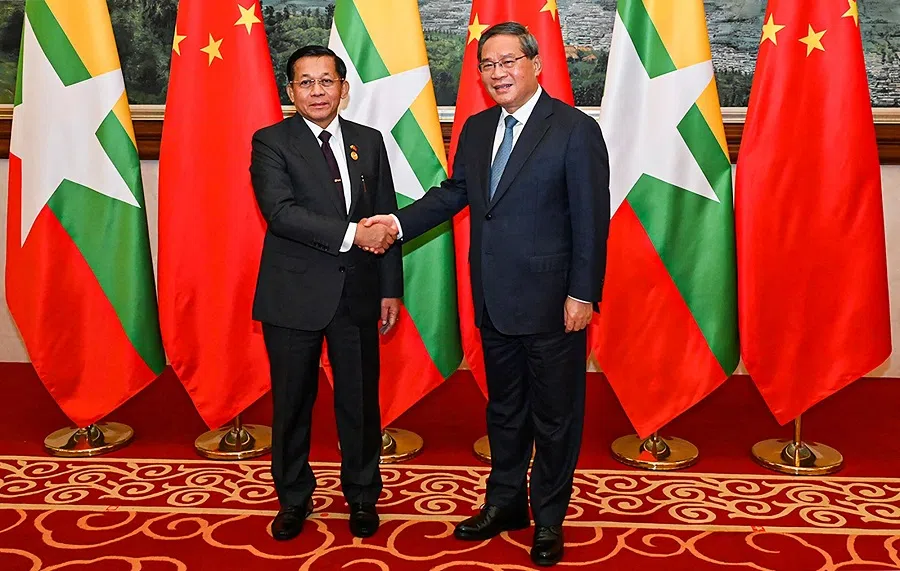

Myanmar’s ruling military junta leader, Min Aung Hlaing, was on a two-day visit to Kunming — the capital of China’s Yunnan province, sharing a 2,027 kilometre-long border with Myanmar — from 6-7 November to attend the Greater Mekong Subregion summit.

On the sidelines of the summit, the high-level delegation led by the junta leader met Chinese Premier Li Qiang. The visit was set against the backdrop of China’s recent decision to impose restrictions on border trade and complete closure of all formal and informal trading points, causing acute inflation in Myanmar and marking a challenging phase in the China-Myanmar relations.

What prompted China to take this major step, and does it signify a response to the increasing operations of ethnic army alliances and their affiliated groups such as the Three Brotherhood Alliance? Given that the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), a member of the Brotherhood Alliance, has expanded its control over large areas of Shan State with the launch of Operation 1027, is China now more focused on stabilising its border regions and managing the effects of Myanmar’s internal conflicts?

All such questions are presented with complex answers, but what seems to be major signalling from this visit is China ending its strategic ambiguity and expressing open support for the junta regime.

Why did China close the border?

One of the critical reasons that China imposed restrictions on border trade and movement was a bomb attack on the Chinese consulate in Mandalay — the second largest city in Myanmar — bordering China to the north and northeast.

China condemned the attack in the strongest words, stating: “China has lodged serious protests to Myanmar and urged the Myanmar side to get to the bottom of the incident, make all-out effort to hunt down the perpetrators and bring them to justice in accordance with law, fully strengthen security measures for Chinese Embassy, Consulate-General, institutions, projects and personnel in Myanmar, and prevent similar incidents from happening again.”

By closing the border trade points, China is likely aiming to cut off the supply chains and economic resources that sustain the ethnic rebel groups in Myanmar.

By closing the border trade points, China is likely aiming to cut off the supply chains and economic resources that sustain the ethnic rebel groups in Myanmar. Many of these groups rely on cross-border trade to fund their operations and smuggling activities and obtain essential supplies, including arms.

By restricting movement and trade, China wants to choke these groups’ access to critical resources, weakening their operational capacities. There remains little doubt that by capturing the junta’s Northeastern Command, the ethnic armed groups have regained control of northern Shan State, resulting in a big blow to the junta’s military operations.

The second reason would be to find alternate strategies to effectively protect its investments in Myanmar through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which includes projects like the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC), cross-border oil and gas pipelines, infrastructure development in the deep-sea port of Kyaukpyu in Rakhine State.

While these projects are critical for China’s energy security and regional connectivity objectives, they are significant in China’s Indian Ocean Region (IOR) strategy as it allows Beijing direct access to IOR, bypassing the Strait of Malacca — very similar to China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which provides China with a strategic advantage by enabling access to the Arabian Sea.

While continuing to support the military junta or State Administration Council (SAC), which seized power in January 2021, China has also militarily empowered ethnic rebel groups.

Since the launch of Operation 1027 by the Three Brotherhood Alliance in October 2023, China has adopted a policy of strategic ambiguity. While continuing to support the military junta or State Administration Council (SAC), which seized power in January 2021, China has also militarily empowered ethnic rebel groups.

This approach aims to pressure the junta into cracking down on cross-border criminal syndicates involved in drug trafficking and cyber scams targeting Chinese nationals, activities that have reportedly flourished in the border region of Kokang under the junta’s protection.

Despite China’s repeated requests, the junta did not act. Finally, Beijing reportedly supported ethnic rebel groups in dismantling these syndicates, as the rebels saw syndicate warlords funnelling protection money to the junta, strengthening the military’s hand in fighting against them.

Is China changing its strategy in Myanmar?

In the last three years, China’s strategic ambiguity was primarily aimed at maintaining its outreach on both ends — the military junta and armed rebel groups. In January 2024, the Chinese vice-foreign minister visited Myanmar and confirmed China brokering peace talks between the two, leading to a temporary ceasefire, which the state media projected as a “China moment” in regional power balance.

The Chinese foreign ministry spokesman had said that the “de-escalation of the situation in northern Myanmar conforms to all parties’ interests and will help maintain peace and stability of the China-Myanmar border”. But the temporary ceasefire quickly failed as both sides continued the attacks.

This brings to mind the 1989 Kokang conflict, when China brokered a truce but struggled to restrain local militias, revealing the limits of external influence in Myanmar’s internal strife.

For the junta, it is the ethnic armed groups failing the China-mediated ceasefire, while the ethnic armed groups blame the junta for carrying out air strikes in northern Shan State and other areas that border China. Some believe that the junta’s military operations against the regions bordering China would not be possible without the support of China because the latter is desperate to restore its economic activities, and the ethnic armed groups have proven to be an unreliable partner.

This brings to mind the 1989 Kokang conflict, when China brokered a truce but struggled to restrain local militias, revealing the limits of external influence in Myanmar’s internal strife. And for the ethnic armed groups, it is China’s selective backing that raises doubts.

Seeing no hope with the ethnic armed groups, China seemingly has ended its strategic ambiguity and come in the open to support the junta regime and its leadership, and an invitation to the junta leader marks China’s endorsement of the current regime in Myanmar.

Without mincing the words, China has also conveyed that it will, jointly with the junta, “crackdown on cross-border crimes such as online gambling and telecom fraud”. And by closing down the border trade posts on the Chinese side, Beijing expects that it will further weaken the ethnic armed groups. However, reconciliation with the junta and choking material supplies to ethnic armed groups may be just one of the steps of China’s current strategy.

The next step for China would be to persuade the junta regime to hold elections in Myanmar, although this might lead to political instability in the region.

The way forward

The next step for China would be to persuade the junta regime to hold elections in Myanmar, although this might lead to political instability in the region. Beijing would want a friendly regime to come to power that aligns with China’s interests and strategic objectives. However, the possibility of unfair and sham elections under the military junta is higher as it is in no mood to hand over power.

The junta has already been making promises to hold elections by November 2025 to pacify global criticism of the state of human rights and democracy in Myanmar. Meanwhile, the polls that can drive fundamental changes in state-society relations, respect federalism, and honour the popular demand for ethnic self-determination can only succeed if they are genuinely accessible, inclusive and safeguarded from military interference.