Beijing’s quiet advance: How China and Saudi Arabia are deepening defence ties

As US–Saudi relations face growing uncertainty, Beijing is quietly expanding its footprint in the Kingdom’s defence and security sphere — through military drills, high-level diplomacy and an assertive presence at defence fairs. Academic Ghulam Ali analyses the deepening ties.

On 13 October, China and Saudi Arabia launched the third joint maritime exercises, dubbed Blue Sword 2025. These exercises, scheduled to run for three weeks, commenced at King Abdulaziz Naval Base in Jubail, the headquarters of the Royal Saudi Navy’s Eastern Fleet. The series began with Blue Sword 2019 in Jeddah and continued with Blue Sword 2023 in Zhanjiang, China.

According to Chinese media, the exercises aim to enhance operational readiness, strengthen tactical coordination, promote knowledge exchange, and increase cooperation between the two navies. As a Western analyst noted, the exercises will provide Saudi Arabia with the opportunity to test interoperability with a non-Western counterpart and to explore alternative tactical approaches, and the Chinese navy with an operational experience in Gulf waters.

Since Saudi Defence Minister Prince Khalid bin Salman Al Saud’s visit to China in June 2024, two-way defence ties have been expanding. Prince Khalid held talks with General Zhang Youxia, Vice Chairman of the Central Military Commission of China, and others, and explored ways to strengthen military and defence cooperation.

The 2019 Houthi drone attacks on Saudi Arabia and the US lukewarm response, as well as the May 2025 Israeli attack on Qatar, a close US ally, have raised doubts about the US commitment to its Gulf allies.

Saudi Arabia-US cleavages

For decades, Saudi Arabia has remained under the US strategic and military influence. Riyadh’s annual defence budget stands at US$78 billion. It is the fourth largest arms importer, with the lion’s share (74%) coming from the US. During US President Donald Trump’s visit to the Kingdom in May 2025, both countries signed a whopping US$142 billion defence deal, which, according to the White House, was the largest arms deal in the history of their bilateral relations.

Despite decades of close strategic alignment, policy divergences between Riyadh and Washington have become increasingly pronounced. The Saudi leadership is ever more concerned about the US commitment to the Kingdom’s security. The 2019 Houthi drone attacks on Saudi Arabia and the US lukewarm response, as well as the May 2025 Israeli attack on Qatar, a close US ally, have raised doubts about the US commitment to its Gulf allies.

Second, Riyadh is unhappy over the US’s reluctance to provide state-of-the-art weapons and technologies to it. For instance, in the ‘historic’ US$142 billion deal, Washington pledged to furnish state-of-the-art warfighting capabilities yet has been unwilling to supply its most sophisticated F-35 to Riyadh. In the region, only Israel operates these aircraft. Similarly, the US has been reluctant to provide civilian nuclear technology, particularly unwilling to allow Riyadh to have indigenous enrichment.

These skirmishes immediately raised China’s defence share and heightened international interest in Chinese systems.

Opportunities for China

China’s role in Saudi defence procurement was limited in the past, largely due to perceptions of lower quality, a limited range of weapon systems, and the absence of real combat testing. However, this perception is changing rapidly.

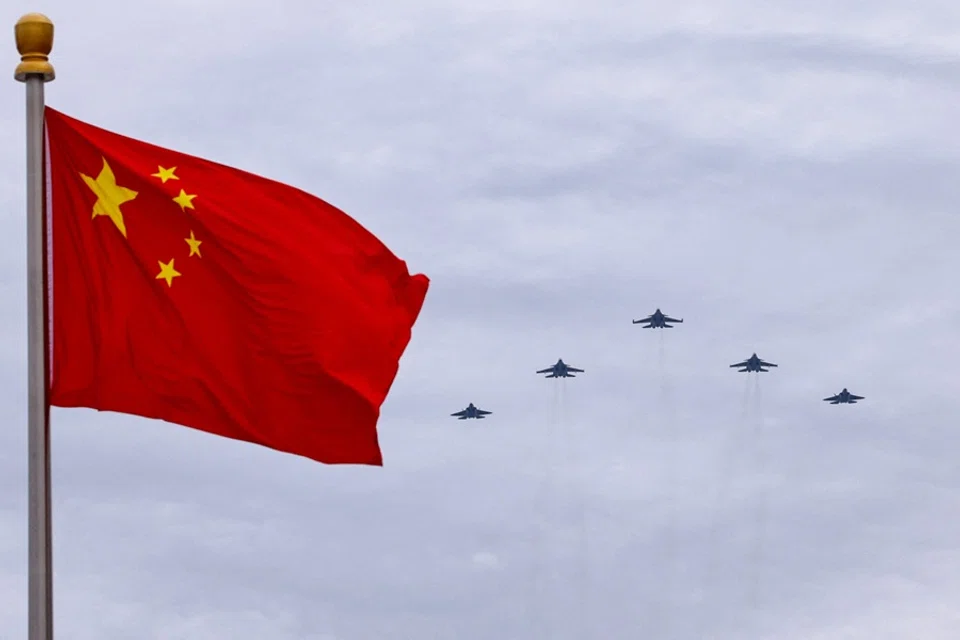

China’s display of newly developed weapons during the Victory Day parade in September 2023, showcasing an extensive and rapidly modernising array of sophisticated weapon systems — spanning next-generation fighter jets, advanced ballistic and cruise missiles, unmanned aerial and maritime vehicles, hypersonic weapons, aircraft carriers, modern surface combatants, armoured ground vehicles, laser-based air-defence systems, and space-based surveillance networks — is changing this perception

Chinese weapons have also gained a real-world combat test. During the four-day clashes between Pakistan and India in May 2025, Pakistan employed China-made J-10s and JF-17s armed with PL-15 missiles. It reportedly downed advanced Western-origin jets, including the French-made Rafale. These skirmishes immediately raised China’s defence share and heightened international interest in Chinese systems. Following that, Indonesia, Bangladesh, and some other states showed interest in Chinese weapons.

Both regional and Western defence analysts recognise China’s leap in defence modernisation. As the Foreign Policy noted, ‘it is no longer correct to say that China is catching up or that it is copying foreign military equipment designs. China is now innovating, and it is leading.’

During the second World Defence Show, held in Riyadh in February 2024, China significantly expanded its footprint, increasing the number of participating defence enterprises from eight to 73.

Parallel with this, China began penetrating Saudi Arabia’s high-value defence market. Since the first World Defence Show (WDS) organised by Saudi Arabia in 2022, China has participated in both biennial editions of the Show. During the second WDS, held in Riyadh in February 2024, China significantly expanded its footprint, increasing the number of participating defence enterprises from eight to 73. China’s national pavilion covered 4,600 square metres, about 9% of the Show’s total space, making it the largest after the host nation.

Converging interests

Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 seeks to localise 50% of defence spending, necessitating technology transfer and flexible supplier terms. While Washington remains reluctant to provide cutting-edge systems to Riyadh to preserve Israel’s qualitative military edge in the region, Beijing’s willingness to export advanced technologies creates natural convergence.

Moreover, China is flexible with technology transfer and free from political strings attached to its weapons exports. Beijing’s defence collaboration with Islamabad serves as a vivid example. Beijing has shown this readiness to Riyadh as well. US reports have claimed that China helped Saudi Arabia in building facilities to produce and possibly test ballistic missiles, specifically linked to the DF-3A (CSS-2) and DF-21 (CSS-5) systems at Al-Watah, southwest of Riyadh.

To some analysts, the Saudi-Pakistani Strategic Mutual Defence Agreement (SMDA) signed in September 2025 could provide additional avenues for China to expand its weapons trade with the Kingdom. This view stems from the fact that Pakistan obtained about 82% of its major arms imports from China in 2019-23, and it maintains deep ties with both countries.

However, there is a caveat. Will the US allow its strategic rival, China, to enter the Saudi arms market, which America has dominated for decades?

If the Blue Sword 2025 is viewed within the broader context of burgeoning Sino-Saudi ties — as evidenced by their bilateral trade reaching over US$107.5 billion in 2024, two-way investments, increased high-level visits, and cultural ties — it could facilitate China’s arms inroads into the vast Saudi market, at least in the conventional weapons domain.

Could a US–Saudi treaty shut Beijing out?

However, there is a caveat. Will the US allow its strategic rival, China, to enter the Saudi arms market, which America has dominated for decades?

The media have reported that Riyadh and Washington might sign a defence treaty during Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman’s visit to the US next month. A formal defence treaty, if signed, could potentially limit China’s strategic ties with Saudi Arabia.

This will not be an easy task, as the US has demanded that Saudi Arabia first normalise relations with Israel. Saudi Arabia has, in turn, linked this process to concrete steps by Israel toward establishing an independent Palestinian state — a condition that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has rejected.

Therefore, until a legally binding defence treaty between Riyadh and Washington is concluded, Beijing is likely to continue expanding its strategic presence in the Kingdom.

![[Big read] Prayers and packed bags: How China’s youth are navigating a jobless future](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/16c6d4d5346edf02a0455054f2f7c9bf5e238af6a1cc83d5c052e875fe301fc7)