BRICS membership a reality check for Indonesia

Now that Indonesia has become a full member of BRICS, it needs a nuanced strategy that maximises the benefits of BRICS membership while minimising its risks, says Indonesian researcher Muhammad Zulfikar Rakhmat.

Indonesia has officially joined BRICS as a full member, marking a significant expansion of the bloc which includes Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, Iran, Egypt, Ethiopia and the United Arab Emirates. The announcement came from Brazil on 6 January, which holds the rotating presidency of BRICS for 2025. Brazil confirmed that the decision was made through consensus among member states.

Indonesia’s decision to join BRICS signals an ambitious step toward reshaping its global economic alliances. However, the move comes with profound strategic risks, particularly as the global economic landscape faces heightened tensions and Indonesia finds itself in a more precarious position than ever before.

By joining BRICS as a full member, Indonesia risks being seen not as an independent player in the global south, but as part of a China-Russia axis.

Aligning with the global south

The allure of BRICS lies in its promise to counterbalance the dominance of Western-centric alliances like the G7. For Indonesia, joining this bloc presents an opportunity to align itself with the global south, fostering solidarity and promoting alternative pathways to economic development. The bloc’s collective push for de-dollarisation — reducing reliance on the US dollar in international trade — positions it as a formidable challenger to Western economic hegemony but could also invite retaliatory measures from the US.

However, there is a much deeper and more immediate strategic dilemma that Indonesia faces in joining BRICS — one that is complicated by the return of a more adversarial global order. The worst thing for Indonesia right now, particularly with Donald Trump returning to power, is the return of a bipolar global system, where the lines between East and West will be firmly drawn. By joining BRICS as a full member, Indonesia risks being seen not as an independent player in the global south, but as part of a China-Russia axis. In the eyes of the West, Indonesia will no longer be merely an external partner engaging with BRICS but a fully integrated member of a bloc that is increasingly associated with Beijing and Moscow.

Possible misalignment with bloc’s geopolitical orientation

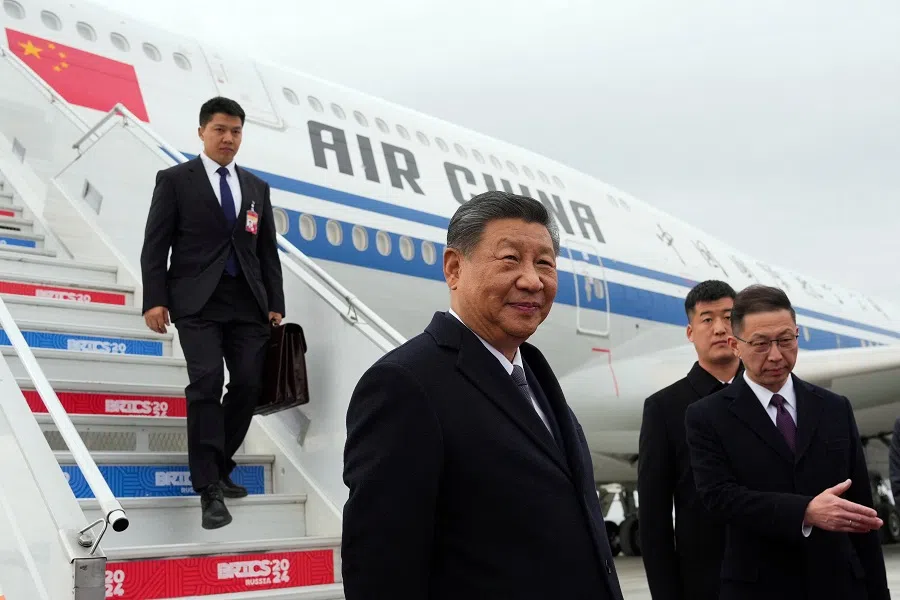

China’s dominant role in the BRICS is well known and Russia’s dominant role in shaping BRICS’ geopolitical narrative was evident during the Kazan summit last year, where Russia’s assertive stance on certain issues seemed to overshadow the preferences of other members, including India. Despite India’s hesitations and differing views, Russia continues to guide the bloc’s narrative on issues like countering Western influence and increasing alignment with China. This internal power dynamic raises further concerns for Indonesia, which may now find itself aligned with a bloc whose geopolitical orientation it does not fully control.

If Indonesia had remained a mere partner of BRICS, it could have continued to engage with the bloc without fully committing itself to the political dynamics within. This would have allowed Indonesia to carefully assess the shifting global alliances without risking its image as a neutral, non-aligned state. But now that Indonesia has taken the step of full membership, it has lost the option to “opt-out” or reframe its relationship with BRICS should it find the geopolitics of the bloc uncomfortable.

... the perception of Indonesia’s shift toward China and Russia could have significant implications for its relationships with Western powers.

A shift towards Russia and China?

Moreover, the perception of Indonesia’s shift toward China and Russia could have significant implications for its relationships with Western powers. This alignment could place Indonesia in a difficult position if geopolitical tensions between the West and the China-Russia axis escalate. The country may find itself caught between the competing demands of great powers, with fewer options to maintain a neutral or independent stance.

Donald Trump’s presidency in the past was marked by aggressive trade policies, including imposing tariffs and enacting protectionist measures. As Trump returns to power, BRICS members are threatened with increased scrutiny and punitive actions. Indonesia, as a new member of the bloc, risks being caught in the crossfire of escalating trade tensions between the US and China. Such measures could include steep tariffs on exports or restrictions on investments, both of which could have profound implications for Indonesia’s economy, particularly its export-dependent sectors.

Not to mention that Indonesia’s participation in BRICS is often viewed through its relationship with China, the bloc’s dominant economic power. While deeper ties with China could offer significant benefits, such as increased trade and investment, over-reliance on one partner presents notable risks. China’s economic slowdown, driven by factors like high youth unemployment, a troubled property market and reduced domestic consumption could have far-reaching effects.

As China’s demand for raw materials and commodities declines, countries like Brazil, a major BRICS member, may see reduced export revenues, which could affect broader BRICS cooperation. Additionally, China’s waning economic strength could reduce its capacity to fund large infrastructure projects within the Belt and Road Initiative, impacting BRICS nations reliant on Chinese investments. Given that China is responsible for a significant portion of global growth, its slowdown could also create a ripple effect, lowering demand for goods and services worldwide, including from BRICS countries.

By diversifying its engagements within BRICS, Indonesia can not only balance its reliance on China but also position itself as a leader in fostering regional cooperation in Asia, Africa and Latin America.

To mitigate these risks, Indonesia should particularly focus on diversifying its relationships within BRICS, engaging with countries beyond China to unlock new opportunities. While Indonesia’s relationship with China is crucial, building stronger ties with other BRICS members — such as Brazil and South Africa — would open avenues in sectors like sustainable agriculture, renewable energy, and infrastructure development.

For example, Brazil’s expertise in agriculture and South Africa’s leadership in renewable energy align with Indonesia’s own economic and environmental goals. By diversifying its engagements within BRICS, Indonesia can not only balance its reliance on China but also position itself as a leader in fostering regional cooperation in Asia, Africa and Latin America. Strengthening these relationships within the bloc would provide Indonesia with a more stable, multi-faceted network of partners, reducing the potential economic risks of dependency on a single dominant partner like China.

The spectre of de-dollarisation also looms large over Indonesia’s BRICS membership. While reducing reliance on the US dollar aligns with the bloc’s long-term vision, the transition could be fraught with challenges. The global financial system’s entrenched reliance on the dollar means that any abrupt moves toward de-dollarisation could disrupt trade and investment flows. For Indonesia, whose economy is intricately tied to international markets, such disruptions could exacerbate existing vulnerabilities, including a potential decline in export volumes to dollar-dependent markets.

Furthermore, Indonesia must contend with the domestic debate over its BRICS membership. Critics argue that the benefits of aligning with the bloc remain uncertain, particularly given the dominance of China within BRICS. Sceptics caution against replicating existing economic dependencies, advocating instead for a more balanced approach that prioritises bilateral diversification. This perspective underscores the need for Indonesia to leverage its BRICS membership to foster equitable partnerships rather than reinforcing asymmetrical power dynamics.

Maximising benefits while minimising the risks

Indonesia’s path forward requires a nuanced strategy that maximises the benefits of BRICS membership while minimising its risks. First, Indonesia should champion green investment initiatives within the bloc. By positioning itself as a leader in sustainable development, Indonesia can attract investments that align with its long-term goals, such as transitioning to renewable energy and fostering environmentally friendly industries. This approach would not only bolster Indonesia’s economic resilience but also enhance its standing within BRICS as a forward-thinking member.

Second, Indonesia must advocate for greater inclusivity and equity within BRICS. The bloc’s success hinges on its ability to address the needs of all its members, not just its dominant players. By pushing for collaborative projects that benefit all members, Indonesia can ensure that its interests are adequately represented. This could include initiatives in infrastructure development, technology transfer and capacity building, which would enhance Indonesia’s economic competitiveness while strengthening the bloc’s cohesion.

Indonesia should adopt a pragmatic approach to de-dollarisation. Rather than rushing to abandon the US dollar, Indonesia could explore gradual transitions that minimise disruption.

Finally, Indonesia should adopt a pragmatic approach to de-dollarisation. Rather than rushing to abandon the US dollar, Indonesia could explore gradual transitions that minimise disruption. This might involve increasing the use of local currencies in trade with BRICS members while maintaining dollar-based transactions with other partners. Such a balanced approach would enable Indonesia to participate in the bloc’s long-term vision without compromising its immediate economic stability.

Indonesia’s decision to join BRICS reflects its ambition to play a more prominent role on the global stage. However, this ambition must be tempered with caution and strategic planning. The challenges posed by potential US protectionism, over-reliance on China, and the complexities of de-dollarisation underscore the need for a measured approach. By leveraging its membership to foster sustainable growth, diversify partnerships and advocate for equitable collaboration, Indonesia can navigate the complexities of BRICS and secure its place as a key player in the evolving global order. However, the country must remain vigilant, as it risks becoming entangled in geopolitical struggles beyond its control.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)