Canada turns pragmatic — and looks East

Canada is recalibrating its foreign policy toward economic interests, flexible coalitions and Asian partners. Engagement now trumps alignment — even as dependence on the US sets firm limits, says researcher Diya Jiang.

In his closely watched speech at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Canada’s Prime Minister Mark Carney declared that his country, alongside fellow middle powers, must “actively take on the world as it is, not wait around for a world we wish to be”.

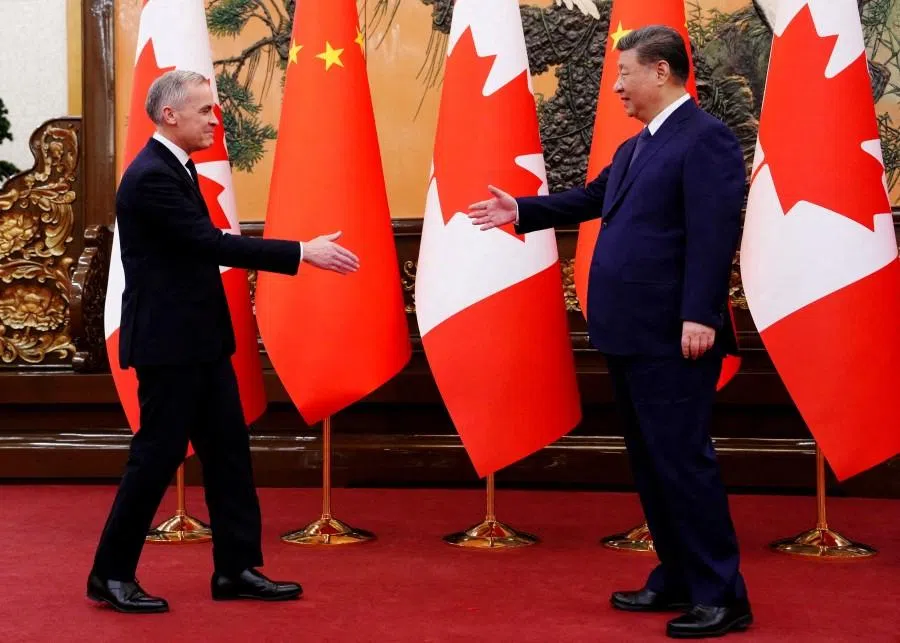

The remark came at the end of a nine-day trip that took Carney from Beijing to Switzerland, passing by Doha, during which he signed highly mediatised partnerships with both China and Qatar in trade, energy and investment. This marked a clear departure from the last decade, during which Canada’s engagement with non-Western allies was largely limited to the ideational and value-based realms. By pursuing meaningful economic agreements with both countries, and touting the benefits of doing so on the Davos stage, Canada signalled a foreign policy recalibration in real time.

In recent months, Canada’s international engagement has instead focused on energy security, critical minerals, technology and investment.

Canadian foreign policy is indeed undergoing its most profound shift in years. It is most visible in three ways. First, Carney’s “value-based realism” places greater emphasis on material interests and economic priorities, moving away from focusing primarily on values that underpinned the Trudeau era. Second, Canada is adopting a more pragmatic approach to multilateralism, relying less on traditional multilateral institutions such as the United Nations (UN) and instead prioritising flexible and adaptable issue-based coalitions. Third, while the US remains a key partner and ally, Ottawa is signalling a push to reduce over-reliance on Washington in both the economic and diplomatic realms.

From values to interests

For the last decade, Ottawa has prided itself on a value-driven foreign policy, most visible through its emphasis on climate leadership, promotion of liberal democratic ideals, and a feminist approach to foreign assistance. These priorities were at the core of Canada’s diplomatic approach on the international stage.

Under Carney’s leadership, we are seeing a divergence to this approach. In recent months, Canada’s international engagement has instead focused on energy security, critical minerals, technology and investment. This includes a newfound willingness to engage with countries such as China and Qatar, who were previously mostly shunned on account of their political systems or human rights practices. As Carney put it in Davos, Canada is “no longer just relying on the strength of our values, but also the value of our strength”.

A more pragmatic multilateralism

Multilateralism and liberal internationalism have long been a core identity of Canada’s post-war foreign policy. A founding member of many multilateral organisations, such as the UN and NATO, Canada has long been committed to engaging the world through its participation in core institutions of the liberal international order.

The shift reflects a belief that cooperation still matters, but that in a more fragmented and competitive world, effectiveness increasingly depends on partnerships based on common ground, even when limited.

While there is no wavering in Canada’s commitment to multilateralism, Ottawa now advocates for “different coalitions for different issues” based on targeted mutual interests. In practice, this means prioritising issue-based cooperation with diverse and flexible groups of countries as well as bilateral dealmaking. The shift reflects a belief that cooperation still matters, but that in a more fragmented and competitive world, effectiveness increasingly depends on partnerships based on common ground, even when limited.

A less US-centric foreign policy

The US has long been much more than just a close ally to Canada. Deep economic integration, shared security arrangements and geographic proximity have, throughout recent history, made a US-centred foreign policy approach both logical and efficient. In many cases, policy alignment with the US has been key in shaping Canada’s relationship with other countries, such as China.

Recent trade tensions and President Trump’s increasing weaponisation of economic linkages have called this approach into question. Against this backdrop, Carney’s push for diversification is less about distancing Canada from the US than about restoring room to manoeuvre. His nascent foreign policy vision allows Canada to engage other partners, including those who hold significantly different systems and values, without treating those relationships as subordinate to a US-led framework.

Implications for Canada-China relations

Canada’s rapprochement with China is the clearest result of Carney’s rapid foreign policy shift. After years of outright hostile relations under the Trudeau government, the two countries agreed to mutually reduce tariffs and deepen cooperation in energy, agrifood, and other sectors.

Given Carney’s goal of doubling non-US exports over the next decade, looking to China, Canada’s second-largest trading partner, is a natural choice. Increasing economic cooperation with Beijing could further his diversification goals more expediently than pursuing numerous trade agreements with countries currently accounting for much more limited flows.

At the same time, Ottawa’s agreement with Beijing does not signal a broader political reset or a move toward strategic alignment with Beijing. However, it delivers concrete economic benefits and reinforces Carney’s case for selective, interest-based engagement with a diverse array of countries.

While engaging with China seems like a natural first step of diversification, Ottawa faces significant constraints both domestically and internationally. Among Canadians, engagement with China remains politically sensitive following years of open hostility between the two governments. A recent public opinion poll found that, despite some improvement, nearly 60% of Canadians surveyed continue to view China negatively.

... Canada-China relations will likely continue to be characterised by limited issue-based engagement in mutually beneficial areas.

Internationally, being seen as getting too close to Beijing could expose Canada to US retaliation at a particularly sensitive time, leading up to United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) renegotiations scheduled for this summer. That risk was underscored last week, when Donald Trump threatened to impose 100% tariffs on Canadian goods, an episode that illustrates how tightly constrained any deeper engagement with China remains

As a result, while relations have warmed compared with the Trudeau years, Canada-China relations will likely continue to be characterised by limited issue-based engagement in mutually beneficial areas. For Carney, ties with Beijing are a recognition of China’s economic importance in Canada’s pursuit of diversification.

Looking ahead

China is just one partner among many that Canada is engaging with a new sense of urgency. Relations with other Asian economies, many of which projected to become among the world’s largest in the coming decades, could see even faster warming as a result of being unconstrained by the political sensitivities associated with Beijing.

As economic power continues to shift toward Asia, Canada’s foreign policy recalibration is less about abandoning old partners than about engaging new ones with clear-eyed pragmatism. The question is no longer whether Canada should diversify, but how far it can do so while managing the constraints that come with dependence and geopolitics. In that balancing act, caution may prove less a weakness than a necessity.