The CCP's massive left turn and the post-Xi political landscape of China

In the name of "Never forgetting the founding mission" (不忘初心), CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping engineered a massive regression to communist orthodoxy, resurrecting ideological indoctrination, tightening control of the media and cracking down on freedom of speech. EAI researcher Lance Gore says this sharp swing to the left has surprised and agitated many in the West and led them to confront and contain what seems to be a renewed communist threat. However, he feels that the rationale for Xi's left turn is misaligned with socioeconomic changes on the ground and the doctrine is thus difficult to sustain. It is in fact more of a generational phenomenon that will come to naught once Xi and his cohort depart from the scene.

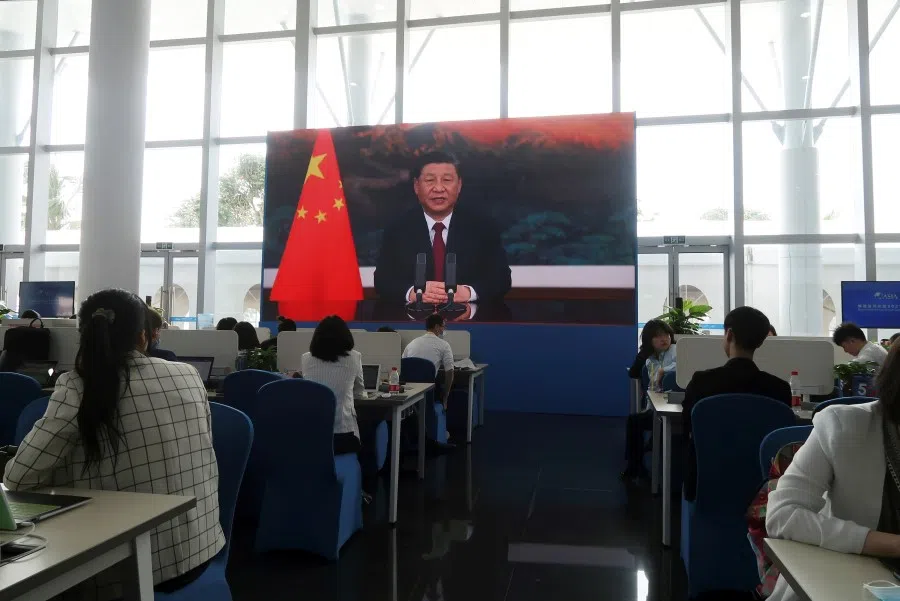

Upon assuming power in late 2012, Xi Jinping engineered a massive recentralisation of power in his own hands and a wholesale return to communist orthodoxy. He assaulted Western liberal ideals such as democracy, the rule of law, human rights, separation of powers, checks and balances, etc. and their underpinning "universal values", vowing China would never reform its political system. Instead, he promoted the "Four Confidences", namely that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is self-confident in the road it has chosen, its guiding ideology, its political system and the Chinese culture.

Subsequently, the Xi regime tightened media control, intensified ideological indoctrination and resurrected many Maoist traditions such as "mass line", criticism and self-criticism, the use of role models, class struggle, anti-peaceful evolution, the party leadership in all areas and affairs of the country and so on.

Xi's left turn

The massive left turn took everybody by surprise. The draconian measures associated with it have triggered a backlash from liberal democracies that threatens China with a new Cold War. How should we interpret Xi's sharp left turn? The real-world conditions in China do not warrant such an abrupt turn. It is a turn by choice rather than by necessity.

This article argues that the left turn is a generational phenomenon associated with the formative experiences of Xi's generation. However, the preceding decades have seen the country evolving decisively away from the communist grand tradition. And because of this inconsistency, the conservative turn lacks broad-based support in society and hence long-term sustaining power.

In an electoral democracy, the age of candidates contending for public offices hardly matters. What matters is whether their personality and message connect well with voters. The American electorate had voted into the White House youthful leaders such as John F. Kennedy and Barack Obama; it had also installed in office much older candidates such as Donald Trump and Joe Biden. In the last two general elections, the candidate who connected best with young, college-educated voters was in fact, 79-year-old Bernie Sanders.

Modern society is generally youth-centred due to the fast-paced changes in all areas; it emphasises the renewal of knowledge more than the accumulation of experiences, and innovations more than traditions. It hence favours young people and marginalises older folks.

The situation in China, however, is the opposite. In the absence of electoral democracy, Chinese top leaders tend to rise in age cohorts, successively working their way up the career ladder one step at a time. It is fairly predictable that by the time they reach the top at the Politburo Standing Committee, they are in their 60s or even early 70s, which is at least two or three generations removed from the youngest adult population.

Xi has a strong sense of historical mission to carry on the cause of his father's generation. Rebuilding the Communist Party through an anti-corruption campaign, and reviving the ideological faith and discipline have been at the top of Xi's political agenda to date.

Battle-hardened by the Cultural Revolution

Xi's generation of "sent-down youths" was battle-hardened in the turbulent years of the Cultural Revolution, which also disrupted their formal education. During their socialisation, communist slogans, jargons, scattered ideas and fragmented theories were the only game in town. Maoism framed their minds and furnished their vocabulary, and became a legacy that follows them to this day.

Xi's childhood hero was Jiao Yulu, party chief of Lankao county in Henan province, who worked until his death from lung cancer. Since becoming the top leader, Xi has travelled to Lankao county several times to pay homage to Jiao. Xi's narrow exposure in his formative years has made Maoism second nature to him, thereby constraining his political horizons.

Xi and other political elite from his generation, unlike their peers in other walks of life, tend to regard their ordeal during the Cultural Revolution as both character-building and part of the qualification for their advancement in politics. This is not entirely idle talk - Xi's commitment to the eradication of poverty reflects the seven years of hardship he underwent with the peasants in northern Shaanxi in the early 1970s.

Boosted by their pedigree and China's meteoric rise, the Xi government's leadership is more confident. This confidence coupled with their incomplete education, make them bolder, brasher and less predictable, as is evident in Xi's drastic recentralisation of power and assertive foreign policy.

Xi has a strong sense of historical mission to carry on the cause of his father's generation. Rebuilding the Communist Party through an anti-corruption campaign, and reviving the ideological faith and discipline have been at the top of Xi's political agenda to date.

Xi has brought back not only Maoist practices but also Maoist vocabulary. His characterisation of his mission as a "great struggle, great project, great cause and great dream", and his "ideological and political party-building" are taken straight from the Maoist revolutionary legacy. The emphasis on class struggle from the Mao era has also instilled in his generation an exaggerated sense of the enemy; they see conspiracies everywhere and tend to approach their job as combatting real or imagined threats. As a princeling, he also absorbed the ethos of the revolutionary generation from his parents.

Chinese politics evolves around an older generation of leaders who are charting the course for the nation, while Chinese society is becoming increasingly youth-centred as in other modern countries.

Youthful polity led by older generation of leaders

More importantly, the absence of electoral pressure and the hierarchical power structure have opened up a broad avenue for their cumulative past experiences to shape the policy direction and political course of the party-state. This creates a situation where Chinese politics evolves around an older generation of leaders who are charting the course for the nation, while Chinese society is becoming increasingly youth-centred as in other modern countries.

Due to the rapid changes and fundamental transformation that China has gone through in the past four decades, the formative experiences, values, worldview and approach of the older leaders may well be misaligned with the real-world situation, but unlike politicians in a democracy, they are in a position to impose and enforce their views on the country. In other words, the generation factor looms much larger in Chinese politics than in a liberal democracy. It exerts its influence through the following channels among others.

The first is the seniority-based pecking order in a strictly hierarchical power structure. The nomenclature system, in which all important positions are appointed from above, is the institutional foundation of the pecking order; it creates an upward dependence of almost everyone in the system upon their superiors. The power hierarchy manifests itself in every operational detail of the political system, from the seating of officials at a meeting, to the group formation of cadres during public appearances, to the way they address each other, as well as numerous other norms and tacit rules.

This pattern is greatly reinforced by Xi Jinping's massive recentralisation of power in his own hands and his incessant demands for absolute loyalty and obedience, as well as his insistence that other Politburo Standing Committee members regularly report to him about their work. The result is a reduced counterweight to his power. Xi then possesses increased freedom to push for his own vision, preferences and ambitions, and to express his inner self which was developed in his youth. In general, the higher an official moves up the ladder, the greater power and freedom he has in fulfilling his personal ambition.

Self-perpetuating state of affairs

Thus, the system is geared towards self-perpetuation. As the power structure works to the advantage of senior leaders, there are few incentives within the system to change it. The political structure is highly stable and almost fireproof to disruptive reform initiatives from below. The party-state's control of vast instruments of propaganda, ideological indoctrination and physical coercion, also allows it to indulge the illusory belief that it can reshape society in its image. As Xi relives his youthful ideals, he is bringing a "blast from the past" to China's age of reform.

Secondly, as successive generations of cadres come to power in age groups, each cohort shares similar formative experiences such that its members understand each other better than perhaps with other cohorts. Each cohort also tends to form a relatively self-contained speech or even policy community sharing familiar jargons, idioms, values, worldviews and commitment that reflect its shared history. In theory, the top cohort is the farthest removed from the youthful population at the bottom. These generational gaps bring about political changes in a gradual but steady manner, because changes at the ground level would eventually reach the top through successive generations of rising cadres.

The future by definition is in the hands of the younger generation who are at the forefront of socioeconomic changes. They have an innate tendency to resist the old-fashioned teachings of their elders, even if they have to pay lip service to these teachings. Junior cadres in China tend to faithfully abide by the Dengist strategy of "maintaining a low profile and biding time" (taoguang yanghui, 韬光养晦), a time-honoured survival strategy in the Chinese officialdom. As a result, there is a lack of genuine policy debate while passivity remains the dominant form of resistance in the political system.

The new leaders may have to search for better ways to accommodate diversity both within and outside the CCP. The party-state may have to be decentralised again, cultivating diverse talents and building alternative institutions.

What would a post-Xi generation look like?

What can we expect from the post-Xi Jinping generations who spent their formative years in the reform era?

It is in fact, difficult to say when the "post-Xi" era would begin because of the removal of term limits in 2018. However, there is no doubt that the composition and characteristics of the political elite are shaped by the party's recruitment and promotion policies. Under Xi Jinping, loyalty, political and ideological criteria have once again been emphasised (as Mao did during the Cultural Revolution), but the CCP will continue to need highly skilled people to fulfil its dream of national rejuvenation. The post-Xi era would see China increasingly competing at the top level in all areas with the most advanced capitalist democracies under the conditions of globalisation.

As the fourth industrial revolution calls for a networked and decentralised economic and social structure, there will be political ramifications, Chinese political elites would have to operate in a different environment requiring different skillsets and expertise. The hierarchical model that the CCP feels most at home with may be seriously impacted. Besides having more independent-thinking future cadres, the rise of entrepreneurial technocrats who embrace a professional ethos and resist ideological dogma will not be surprising. Under such circumstances, the rigid hierarchy reinforced by Xi Jinping may put China at a disadvantage and post-Xi leaders may have to dismantle the excesses of Xi's legacy. The new leaders may have to search for better ways to accommodate diversity both within and outside the CCP. The party-state may have to be decentralised again, cultivating diverse talents and building alternative institutions.

The top leadership today consists of cadres who grew up in the 1950s and 1960s in conditions unimaginable for generations that came of age in the reform era. Their material provisions, education and family background, value orientation, exposure to the outside world, career trajectories and the focal points of their respective lives are essentially different - they do not speak the same language. The younger generation can adapt better to rapid socio-economic changes. The experiences and skills of the older generations accumulated from the Mao era are essentially of no use in the new era. Yet, in politics, the older generation is calling the shots.

Historically, ideological indoctrination and information control have achieved but a superficial conformity as attested to by the sudden collapse of the Eastern Bloc. It is even more superfluous with increasing social pluralism in a decentralised setting. Furthermore, orthodox Marxism and Maoism have played no positive role in China's market-driven developmental success during the reform and opening era. They may well have undermined it.

China's future direction is therefore far from set in stone. Treating China as a rising communist threat, as the West is increasingly doing, may lock it onto a path towards that destiny in a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Changes afoot whether the leadership likes it or not

Yet Xi seems oblivious to the fact that more than any time in the PRC's history, the ideological and value differences today are rooted in society's diverging material interests. Xi's efforts at homogenising people's thinking, mainly by beefing up the indoctrination machinery and stifling voices of dissent, shows that he is being trapped in the Maoist past instead of adapting to today's realities. The Marxism that Xi relishes now, does not go beyond the "standard answers" to what was taught in the political study sessions during the Cultural Revolution. As a vestige of the past, it is crude and largely irrelevant to the everyday life of the general population.

For the general population, the one-child generation and the millennials are living and growing up in a brand new environment. This is a generation of "little emperors" indulging in capitalist consumerism and constantly pursuing the latest lifestyle fads. They want to be seen as "cool" instead of "red". They are also the internet generation who control vast amounts of information at their fingertips and are exposed to all kinds of ideas.

According to researchers and observers, this is a generation characterised not only by being "selfish", "self-centred", "spoiled", "rebellious", "anti-traditional", "irresponsible" etc., but also by having "strong self-confidence, diverse interests, and a strong need for self-improvement", as well as being "more tolerant to differences, including differences in values and lifestyles".

These traits make up the milieu that whoever comes to power will have to work with. It is against this milieu that many of Xi's efforts at restoring orthodoxy are likely to be futile. Most importantly, the force of this social milieu may inevitably infiltrate the ruling communist party via diversified party membership. Some of them may eventually reach the top leadership in the future.

China's future direction is therefore far from set in stone. Treating China as a rising communist threat, as the West is increasingly doing, may lock it onto a path towards that destiny in a self-fulfilling prophecy. This may lead to a new Cold War, prematurely and unnecessarily. However powerful the party-state is and however hard it attempts to shape socioeconomic changes, it will not be able to turn the tide. A "peaceful evolution" may be inevitable, even if it is not in the exact shape the West hopes for.

The biggest threat to this scenario, however, is the inability of liberal democracies to resolve the pressing governance problems of their own. This inability will turn off future Chinese leaders and vindicate their practice of continuing to embrace the old orthodoxy by default. After all, the current system serves their personal interests well.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)