Diplomatic schedule for China and Japan edging closer

Relations between Japan and China have been cool at best, but going by recent developments, it looks like efforts are being made to bring both countries closer, amid the context of Trump’s second term as US president. Academic Hao Nan analyses the situation.

After years of diplomatic frost, China and Japan appear to be making cautious steps toward rapprochement. On 13-15 January, a Japanese ruling coalition delegation headed by secretary-general Hiroshi Moriyama of the Liberal Democratic Party and secretary-General Makoto Nishida of the Komeito Party visited Beijing. They attended the 9th meeting of the China-Japan ruling parties exchange mechanism, after a seven-year hiatus, discussing ways to improve the bilateral relations.

This visit coincided with an announcement on 13 January that a delegation from the Eastern Theater Command of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) will visit Japan in mid-January and meet with leaders of the Japanese Ministry of Defense and the Joint Staff of the Self-Defense Forces. These events mark the revival of dialogue channels that have been dormant over the past years. While this suggest a thaw in relations, the backdrop of the rapprochement is fraught with challenges that may test the durability of this emerging diplomacy.

... despite these tensions, an uptick in high-level diplomatic exchanges since late 2024 indicates a shared interest in exploring pathways for cooperation.

For much of the past decade, China-Japan relations have been shaped by deepening distrust and rising tensions. Japanese leaders, from Shinzo Abe to Fumio Kishida, have framed a potential “Taiwan emergency” as a direct threat to Japan, echoing comparisons between Ukraine and East Asia. This rhetoric has been matched by a dramatic shift in Japan’s defence posture, including plans to raise its defence budget to 2% of GDP by 2027 and acquiring “enemy base strike capabilities”.

Revisions to Japan’s longstanding pacifist policies, such as the loosening of arms export restrictions, have further solidified its break from post-war norms. Japan has also risen into a central role in the US and allied nations’ so-called minilateral initiatives including the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue; the US-Japan-South Korea Trilateral Partnership; the Squad comprising the US, Japan, Australia and the Philippines; the US-Japan-Philippines Partnership; and the US-Japan-Australia Partnership, which China perceives as part of a US-led containment strategy.

Military developments

Meanwhile, China’s growing active presence in the East China Sea has fuelled Japan’s concerns. Following Japan’s controversial 2012 nationalisation of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, Chinese coast guard activities around the disputed waters have surged. In 2024, the Japanese government reported a record 355 days of Chinese coast guard activity, the highest since tracking began in 2012.

Adding to Japan’s concerns, China’s military — often working in tandem with Russia’s manoeuvres in the West Pacific — has ramped up operations in the Sea of Japan and frequently conducted incursions through key Japanese maritime straits. In December 2024, the Chinese military staged provocative drills simulating the blockade of the Miyako Strait, a critical corridor for Japanese and US naval forces in a potential Taiwan contingency. Incidents involving attacks on Japanese citizens in China have further strained public opinion in Japan. Yet despite these tensions, an uptick in high-level diplomatic exchanges since late 2024 indicates a shared interest in exploring pathways for cooperation.

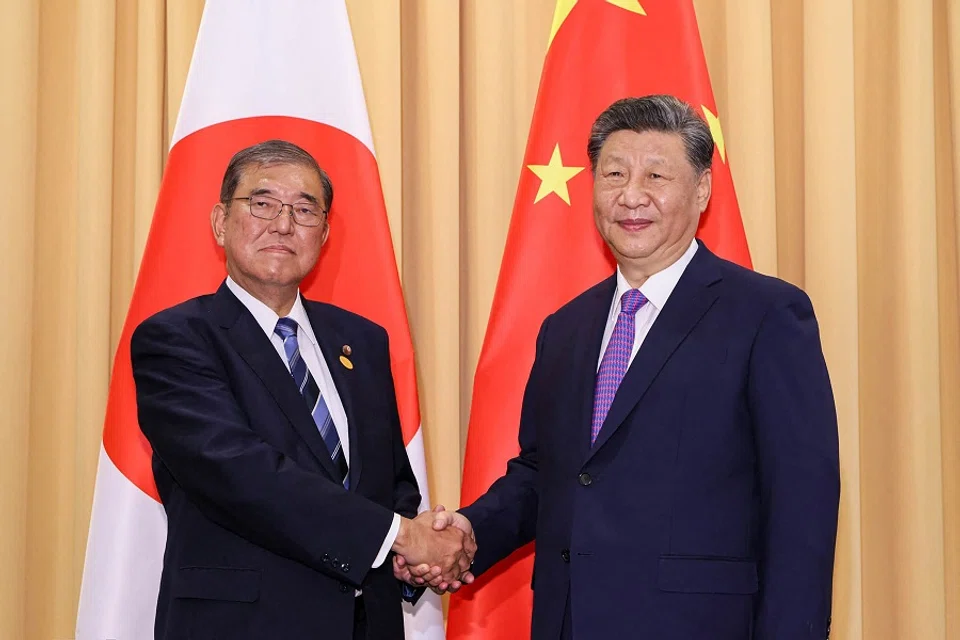

The recent flurry of diplomatic activity between Tokyo and Beijing underscores the complexities of the relationship. Japanese Foreign Minister Takeshi Iwaya’s visit to Beijing in December 2024 included meetings with his Chinese counterparts Wang Yi and Premier Li Qiang, signalling a desire for dialogue. This followed a series of interactions: Japanese national security adviser Takeo Akiba met with Wang Yi for a marathon 4.5-hour meeting in November and Chinese President Xi Jinping had a sideline discussion with Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba during the APEC summit in Peru that same month. These meetings set the stage for further engagement, with China’s Wang Yi expected to visit Japan in February to resume the long-suspended Japan-China High-Level Economic Dialogue and possibly having the next Japan-ROK-China trilateral foreign ministers’ meeting.

But the obstacles remain formidable. Public opinion in both countries is a major hurdle. A history of territorial disputes and wartime grievances has fuelled mutual distrust, and recent incidents, such as attacks on Japanese nationals in China, have further soured perceptions. Japan’s domestic politics add another layer of complexity. Prime Minister Ishiba’s minority government is vulnerable, particularly as it faces a contentious budget session in March 2025. The opposition’s resistance to Ishiba’s leadership could complicate any efforts to make bold diplomatic moves, including a potential visit to China ahead of a visit to the US.

... it could pave the way for Chinese Premier Li Qiang’s visit to Japan, followed potentially by a reciprocal visit from Ishiba to China. Such exchanges could culminate in a groundbreaking visit by Chinese President Xi Jinping to Japan, an event that would carry significant symbolic weight.

Japan-US relations

Meanwhile, Japan’s relationship with the US looms large in its foreign policy calculus. Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba has expressed strong commitment to strengthening the US-Japan alliance, emphasising its critical importance to regional security. However, ties with Washington have recently encountered turbulence.

Despite Japan’s consistent alignment with the Biden administration’s domestic and foreign policy agenda, a recent controversy has cast doubt on the reliability of the US as a partner. Nippon Steel’s attempted acquisition of US Steel became the flashpoint of this tension, as the Japanese company accused the Biden administration of “illegal interference” in the deal.

On 6 January 2025, Nippon Steel and US Steel officially filed a lawsuit against President Biden and senior US officials, alleging a violation of their legitimate corporate rights, marking an unprecendented lawsuit by a major Japanese corporation involving a sitting US president. On 13 January, Ishiba himself asked President Biden to allay concerns in the Japanese and US business communities over the case of Nippon Steel, despite the trilateral nature of the US-Japan-Philippine virtual summit.

Compounding the strain, Ishiba’s efforts to build rapport with President-elect Donald Trump have met with mixed results. In November 2024, during Ishiba’s trip to Latin America for the APEC and G20 Summits, Trump declined a request for a meeting citing legalities but notably welcomed Akie Abe, the widow of former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, to his Mar-a-Lago residence for a private meeting.

While Trump has since signalled availability for a first meeting with Ishiba in mid-January 2025, a prospect Ishiba described as an opportunity to elevate the US-Japan alliance to a new height, Ishiba during a televised programme on 29 December 2024, emphasised the importance for a visit to China. He reiterated this just before the Japanese delegation’s visit to China in January. These statements coincide with his decision to postpone his planned trip to the US until February or later, after Trump’s inauguration. Recent developments likely propelled Ishiba to uphold his traditional advocacy for more equal US-Japan relations, compelling him to further engage Beijing.

For this rapprochement to succeed, both sides must tread carefully. Concrete actions will need to follow the warm words exchanged in diplomatic settings.

Nevertheless, the possible Japan-ROK-China trilateral foreign ministers’ meeting, to be held alongside the Japan-China High-Level Economic Dialogue in February, offers a glimmer of hope. If successful, it could pave the way for Chinese Premier Li Qiang’s visit to Japan, followed potentially by a reciprocal visit from Ishiba to China. Such exchanges could culminate in a groundbreaking visit by Chinese President Xi Jinping to Japan, an event that would carry significant symbolic weight. As per Chinese diplomatic practice, Xi’s visit would mark a potential turning point, upgrading the current “China-Japan strategic relationship of mutual benefit” since Abe Shinzo’s era to a more robust partnership well positioned into China’s hierarchical diplomatic partnership pyramid.

For this rapprochement to succeed, both sides must tread carefully. Concrete actions will need to follow the warm words exchanged in diplomatic settings. Beijing might have to address Japan’s concerns over security issues in the Sea of Japan and East China Sea, while Tokyo must navigate the delicate task of engaging with China without alienating its allies, particularly the US. Trust-building measures, such as agreements on crisis management or economic cooperation, could help stabilise the relationship.

In a world increasingly defined by great power competition, the prospect of China and Japan bridging their divides is a development worth watching. While their histories and interests diverge in significant ways, their fates are intertwined as key players in the Indo-Pacific. The steps taken in early 2025 could either mark the beginning of a new chapter in their relationship or become yet another footnote in the long saga of missed opportunities.