Good Malaysia-China relations: Better lives for Chinese Malaysians?

Turning opportunities from China into gains for Malaysia depends very much on Malaysia’s own good governance and internal stability, says Malaysian academic Michael Tai.

At the end of May, Malaysia celebrated the 50th anniversary of bilateral relations with China. In May 1974, then Prime Minister Tun Abdul Razak took the bold step of visiting Beijing to establish diplomatic relations. Formal relations were established on 31 May.

Although the Malayan communists had fought a 12-year war (1948-1960) against British colonial rule and the Vietnam War had not ended, Razak showed unusual foresight and understood the importance of China. Despite the prevailing Cold War narrative, he did not see China as a threat.

For centuries, China had carried out peaceful exchanges with her neighbours within the tributary system, a loose spoke-and-hub framework involving trade, ritual and cultural exchange. Tributary states acknowledged China’s primacy but participated in the system only as they wished. China neither stationed troops in nor colonised the tributaries.

Confucian by nature, the centre treats the periphery with benevolence as a father does his children. Rather than a nation-state along European lines, China is a civilisational state the size of a continent made up of diverse peoples (56 ethnic groups today) that, over time, came to identify with the state’s language, culture and history.

The contrast between European gunboats and Chinese diplomacy was not lost on Razak.

Longstanding ties

Sino-Malay ties date back to Malacca, a maritime power, which became a Chinese tributary state during the reign of the Ming emperor Yongle (1402–1424). But from the 16th century onwards, Malacca was conquered and colonised first by the Portuguese, then the Dutch and finally the British.

The contrast between European gunboats and Chinese diplomacy was not lost on Razak. While others waited, he took the lead to make Malaysia the first Southeast Asian state to normalise its relations with the People’s Republic of China, notwithstanding Malaysia’s deep economic and cultural ties to its former colonial master Britain. Despite membership in the Non-Aligned Movement, Malaysia enjoys close relations with the West, and many of the elite including Tun Razak and his predecessor Tunku Abdul Rahman studied in the UK.

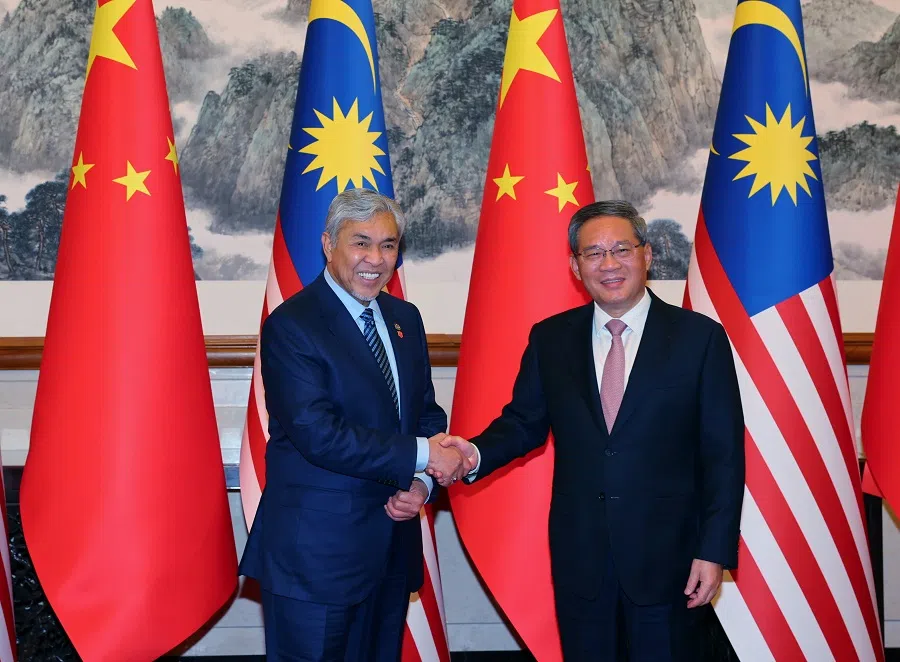

In Beijing from 22 May to 1 June to commemorate the 50th anniversary of diplomatic relations, Malaysian Deputy Prime Minister Ahmad Zahid Hamidi highlighted the two countries’ comprehensive strategic partnership for mutual development and growth.

Warmly welcomed at the Diaoyutai State Guesthouse by Chinese Premier Li Qiang, Zahid thanked the Chinese government for its timely gift of vaccines during the Covid-19 pandemic when millions of Malaysians were affected by the virus and associated economic slowdown. He said the time-honoured friendship between the two nations cannot be broken by any external forces. Malaysia, he reiterated, adheres to the “one China” policy and is against interference, especially in the South China Sea. Despite outside pressure, Putrajaya refuses to take sides in geopolitical contests.

Meanwhile, a video clip of a young Chinese reporter in Beijing interviewing Deputy PM Ahmad Zahid in flawless Malay went viral.

Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim wrote in a Facebook post: “Despite the apparent reasons for refrain — our ideological chasm, our seemingly irreconcilable differences — our leaders dared to think beyond convention and took a bold leap of faith. This audacious move has blossomed into a rich and fruitful partnership. The MADANI government is committed to nurturing this vital relationship for the prosperity of our peoples and the entire region.” He added that he is looking forward to Chinese Premier Li Qiang’s visit to celebrate the “historic milestone” of 50 years of diplomatic ties. Meanwhile, a video clip of a young Chinese reporter in Beijing interviewing Deputy PM Ahmad Zahid in flawless Malay went viral.

Overall, Putrajaya has managed relations to benefit its own national interests, even cancelling high profile infrastructure projects such as the KL-Singapore high-speed rail when deemed necessary. Beijing, on her part, takes the long view and accepts temporary setbacks for the sake of long-term goals.

Malaysia supportive of a just and equitable world order

Instead of confrontation, Malaysia has shown it is possible to find constructive solutions to competing maritime claims. Speaking recently at the annual Future of Asia forum in Tokyo, former Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad urged ASEAN to remain neutral, downplaying China’s claims in the South China Sea. Western double standards are on full display in Ukraine and Gaza. Like many in the global south, Malaysia supports diplomatic initiatives to build a just and equitable world order or what President Xi Jinping calls a community of common destiny for mankind.

The Malaysian government does not want to pick sides although the Gaza war has tilted public opinion against Washington and in favour of China.

President Xi’s vision is rooted in the classical Chinese concept of tianxia or the whole of humanity. It emphasises inclusivity and a ruler’s moral duty to govern justly and benevolently, ensuring harmony and stability. It also prioritises government for the benefit of all rather than for a privileged race or class alone.

Following China’s launch of the Global Development Initiative and the Global Security Initiative, President Xi Jinping proposed the Global Civilisation Initiative which advocates respect for the diversity of civilisations, common values of humanity, and robust international people-to-people exchanges and cooperation.

The US remains Malaysia’s largest source of foreign investments while China is its most important trade partner. The Malaysian government does not want to pick sides although the Gaza war has tilted public opinion against Washington and in favour of China.

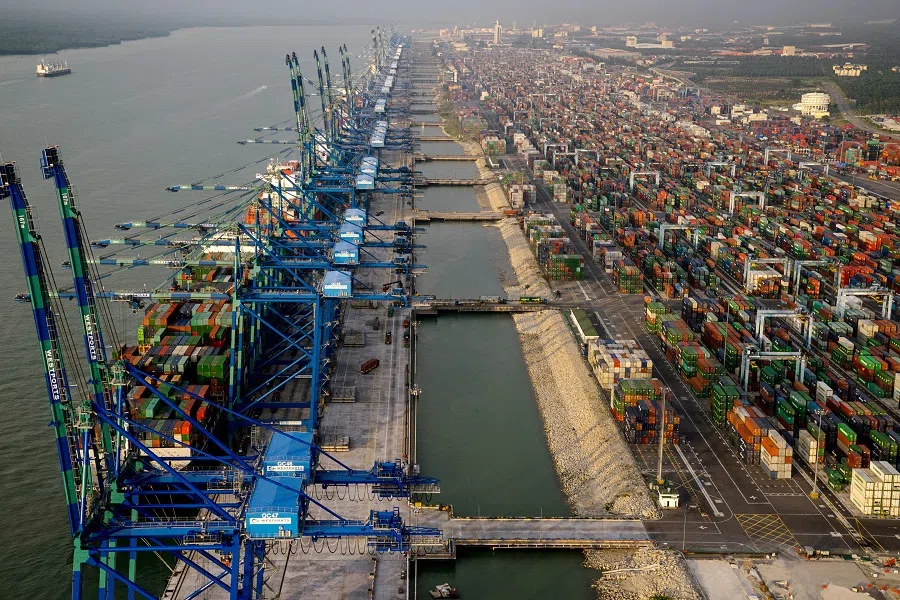

The Chinese have a long institutional memory, and Beijing has not forgotten Razak’s historic initiative. For the last 15 years, China has been Malaysia’s most important trade partner with bilateral trade reaching US$98 billion in 2023. China has committed to invest RM170 billion (US$36 billion) in infrastructure, renewable energy, telecommunications and tourism promising to boost the economy for years to come.

The investment comes at a time when Malaysia is hoping to upgrade its semiconductor industry. The country has hosted electronics companies such as Hewlett Packard, Intel, Samsung and Infineon for decades in assembly, testing and packaging but now wants to move up the value chain into the design and manufacture of semiconductors.

International competition to attract semiconductor and AI investors is intense, and the country will need help to train thousands of skilled engineers. Speaking from Beijing, Deputy Prime Minister Ahmad Zahid urged Malaysian youths to seek higher education in China, signalling a shift from going to the West or Japan.

While English will remain important for years to come, China’s rise as an economic and technological power will see wider use of the Chinese language, and just as French overtook Latin, and English displaced French, Chinese may become the next major lingua franca of the world.

Domestic tensions contrast with warm relations with Beijing which upholds the Five Principles of Peaceful Co-Existence including non-interference in the internal affairs of other states.

Malaysia’s internal tensions against Chinese a point of concern

Malaysia is a multiracial society consisting of Malays, Chinese, Indians and aboriginal communities. Since the 1970s, majority Malays who now comprise 70% of the population have enjoyed special economic, political and social privileges. This has left other races feeling like second-class citizens.

The government has built good ties with China despite local racial tensions, largely because China’s policy of not interfering in the internal affairs of other states reassures Malaysian leaders. Ties with China revolve mainly around business and technology, which Malaysia needs, to boost its economy in the face of intense international supply chain competition.

Domestically, however, Malay politicians are quick to play the race and religion card to win votes, with the recent campaign to boycott a Chinese-owned convenience store chain KK Super Mart being the latest example. The store was accused of insulting Islam when pictures of socks bearing the word Allah in Arabic found in one of its stores went viral. The owner of the chain was promptly investigated by the police and charged in court while three stores were attacked with molotov cocktails but the perpetrators have yet to be arrested.

Since independence in 1957, right-wing Malay politicians have tried repeatedly to ban Chinese and Tamil schools, accusing the vernacular schools of breeding disunity. Domestic tensions contrast with warm relations with Beijing which upholds the Five Principles of Peaceful Co-Existence including non-interference in the internal affairs of other states. Since the Gaza war, the local McDonald’s, Kentucky Fried Chicken and Starbucks franchises have suffered boycotts for alleged links to Israel.

Meanwhile, business with China opens up opportunities for the local Chinese, with bilingual individuals facilitating Sino-Malay deals. This is a role that Chinese merchants in Southeast Asia have played for centuries.

The boycotts deter foreign investors at the very moment when the country seeks to recover from Covid, create employment and move up the value chain even as the government faces severe fiscal pressures stemming from massive losses through corruption (to the tune of RM277 billion or US$59 billion over the last five years). Malaysia is at a crossroads. China’s support could enhance industrial competitiveness but the country’s success will ultimately depend on good domestic governance.

Meanwhile, business with China opens up opportunities for the local Chinese, with bilingual individuals facilitating Sino-Malay deals. This is a role that Chinese merchants in Southeast Asia have played for centuries. Despite adversity, overseas Chinese communities have learned to accept and make the most of their circumstances with or without succour from their ancestral homeland.