India’s strategic conundrum of diminished influence and rising ambitions: State of Southeast Asia 2024

With its strategic relevance in Southeast Asia diminishing, how can India enhance its image as a trusted partner in the region?

The ongoing election in the world’s most populous country is poised to usher in the triumphant return of strongman Narendra Modi for an unprecedented third term. Prime Minister Modi has been playing up India’s rising global status to woo voters. However, despite its role in key organisations such as the G20 and being a comprehensive strategic partner of ASEAN, India is losing its strategic relevance in Southeast Asia.

Decreasing clout in Southeast Asia

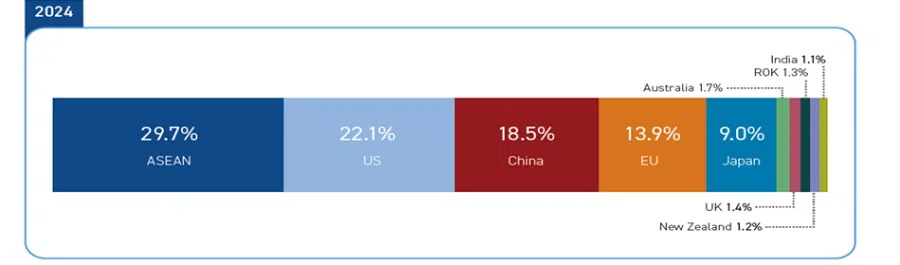

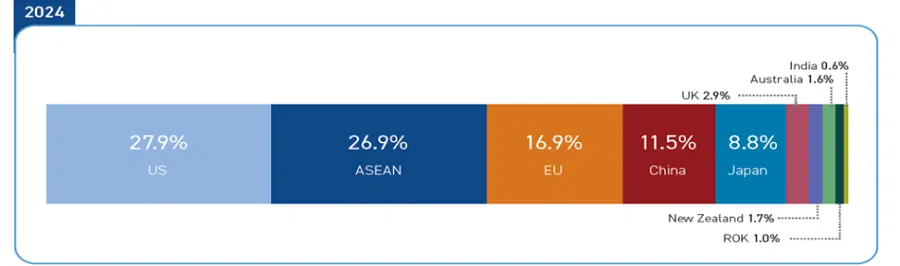

The State of Southeast Asia 2024 Survey report paints a stark picture of India’s diminishing economic and political influence in the region. Among nine major powers including ASEAN and the EU, India emerged as the least influential economic, political and security power. This has been the case since the start of the survey in 2019. This year, India saw a further decline in its rating on the political-and security front from 0.9% to 0.4%, with no respondents from Brunei, Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam choosing the country.

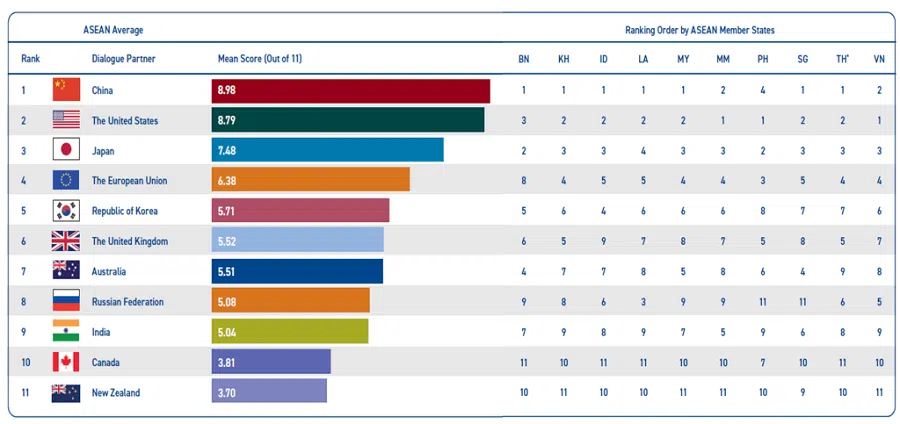

Furthermore, as a rallying force, India ranked ninth among 11 dialogue partners in terms of strategic relevance to ASEAN, ranking even below Russia — a violator of international law. The disparity in ranking across the ten ASEAN countries (from fifth to ninth place) underscores the non-uniform nature of India’s engagement with the region and the variations in perceptions among the various countries.

Myanmar and Singapore, which enjoy historical-cultural connections with India, perceive the country more strategically with their respondents ranking India in the 5th and 6th place respectively. Myanmar is the only Southeast Asian country that shares a long land border with India, while Singapore — India’s largest trade partner in ASEAN — enjoys broad-based and multifaceted bilateral relations with the country.

Despite its active advocacy for the global south, India’s economic relations with Mekong countries like Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam remain lacklustre by any measure and pale in comparison to China’s robust engagement.

Countries such as Cambodia, Laos, the Philippines, and Vietnam which maintain closer diplomatic ties with China, the US, and Russia perceive India as less strategically significant. Despite its active advocacy for the global south, India’s economic relations with Mekong countries like Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam remain lacklustre by any measure and pale in comparison to China’s robust engagement.

Ability to lead and values questioned

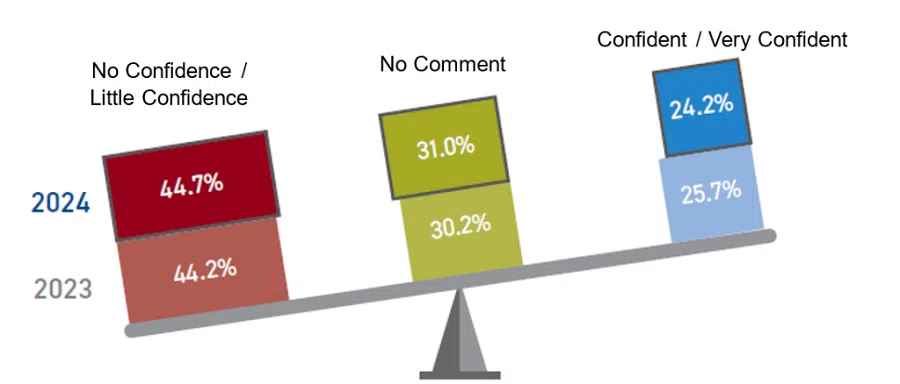

On the normative front, confidence in India’s leadership role in championing global free trade and maintaining a rules-based order has also decreased from last year with India being viewed as the least likely leader in these aspects.

India’s refusal to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and its withdrawal from the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership to protect its own industries points to the prioritisation of domestic interests over broader regional and global responsibilities.

In the same survey, when asked if India will “do the right thing” to contribute to global peace, security, prosperity and governance, a growing number of regional respondents have shown little or no confidence in India.

The biggest group of respondents (40.6%) felt that India does not have the capacity or political will for global leadership, while 26.4% of respondents are concerned that India is distracted with its internal and sub-continental affairs and thus cannot focus on global concerns and issues.

New Delhi’s inward-focused priorities including Modi’s authoritarian tendencies and religious agenda, coupled with declining democratic values and religious freedom, have led to a perception of India being less capable of assuming global leadership.

New Delhi’s inward-focused priorities including Modi’s authoritarian tendencies and religious agenda, coupled with declining democratic values and religious freedom, have led to a perception of India being less capable of assuming global leadership.

These tendencies are exemplified by Modi’s effort to reshape India in its Hindu-nationalist image through the inauguration of the Ram temple in January in Ayodhya (on the site of a 16th-century Mughal mosque) and advocating for the use of “Bharat” as the Sanskrit name for India in official meetings like the G20. India’s goal towards self-reliance such as the “Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyaan” campaign further entrenches its protectionism to the detriment of globalisation and free trade.

A need to see concrete benefits

Externally, even though India remains a crucial partner for the US and other Western countries in countering China, this does not resonate as strongly with Southeast Asians. The region is not concerned with New Delhi’s alignment but rather the concrete benefits it can derive from its engagements with India. The days of India maintaining a stance of having its cake and eating it too may be numbered.

For India to secure a meaningful place as a trusted partner in the region, it needs to address the aspirations of ASEAN countries. On the economic front, there are enormous opportunities for India to integrate into the supply and value chains of ASEAN as multinationals are diversifying their manufacturing away from China.

Greater access to India’s growing market, facilitated by trade liberalisation and improved physical connectivity through initiatives like the India-Myanmar-Thailand Trilateral Highway project (with extension to Laos and Cambodia) will not only increase two-way trade but will boost supply chain resilience.

Beyond economic ties, India’s deep-rooted cultural and religious affinities with the region offer a unique advantage in cultivating soft power influence. By upholding its commitment to religious diversity, India can foster stronger relations with the Muslim-majority countries in Southeast Asia.

... ASEAN remains cautious of India’s broader strategic motives.

As a security partner, India’s longstanding policy of non-alignment will enable it to contribute strongly to maintaining the regional balance of power and to play a greater role as a leader in the global south. The survey underscores India’s status as the region’s third most preferred strategic partner, surpassing countries like Australia, South Korea and the UK in helping ASEAN hedge against the uncertainties of the US-China strategic rivalry.

However, while trying to establish itself as a stronger security partner for the region, its actions are perceived to be driven by strategic considerations, including the need to counterbalance China’s growing influence in the region. Despite efforts such as increased sales of advanced weaponry like the BrahMos missile and conducting joint exercises with ASEAN countries such as the ASEAN-India maritime exercise in May 2023, ASEAN remains cautious of India’s broader strategic motives.

India’s ambitions are valid, but it will be a steep hill to climb, considering its resource constraints and preoccupation with other domestic priorities. It will be a long road ahead for India to emerge as a strategic player in the region.

This article was first published in Fulcrum, ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute’s blogsite.