Navigating Trump: Australia’s path to a more confident foreign policy

While Australians generally view their alliance with the US positively, Trump himself is deeply unpopular in Australia, and he is not trusted to act in ways that are supportive of Australia’s national interest. How is Australia readying itself for Trump 2.0? Australian academic David M. Andrews analyses the situation.

“We seek to cooperate where we can and will disagree where we must. And we will engage in our national interests.” These are the words that Australia’s foreign minister, Penny Wong, first used in November 2022 to describe the Albanese government’s policy toward China. However, with the election of Donald Trump as US president in November 2024, it is an approach that may yet have just as much relevance to Australia’s relationship with its principal ally and security guarantor.

Australian reactions to Trump 2.0

The US is, for Australia, an irreplaceable ally and partner. However, the return of Trump to the White House — meaning his first term can no longer be discounted as an aberration — raises uncomfortable questions for Australian policymakers and exposes political tensions at the heart of the relationship.

... polls consistently indicate that Trump himself is deeply unpopular in Australia, and he is not trusted to act in ways that are supportive of Australia’s national interest.

On one hand, Australia’s 2024 National Defence Strategy acknowledged that the US alliance is “fundamental to our national security and the [Australian Defence Force’s] capacity to generate, sustain and project credible military capability” and the alliance is, in general, viewed very positively by the population. However, polls consistently indicate that Trump himself is deeply unpopular in Australia, and he is not trusted to act in ways that are supportive of Australia’s national interest.

This inherent tension is likely to become harder to manage under a second Trump presidency. Not only will Trump and his team be more experienced in using the levers of power, but the character of his administration looks to be one shaped primarily by personal loyalty and unswerving dedication to the inward-looking, “America First” agenda. Additionally, some of his early policy pronouncements, like the promise to introduce a blanket 10% tariff on all imports, and an additional 10% (up to a total of 20%) tariff on Chinese goods, cut directly across Australia’s economic interests.

If AUKUS were to be cancelled, this would be a disastrous outcome for Australia’s submarine capability.

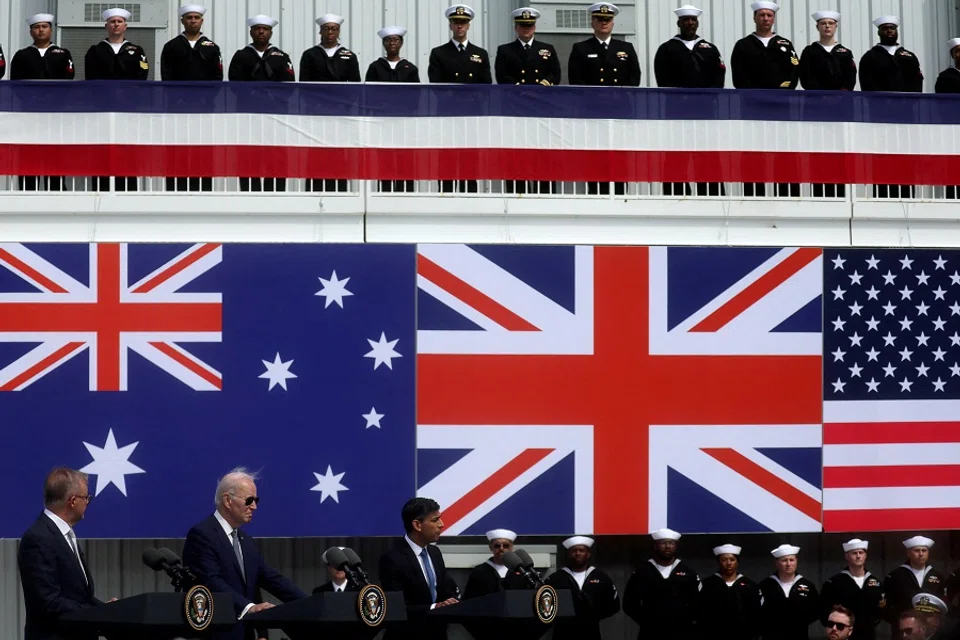

Furthermore, there seems to be concern from members of the Australian government that Trump may look to cancel or renegotiate AUKUS — the trilateral security partnership with the UK and US under which Australia is set to acquire a fleet of conventionally armed, nuclear-powered submarines. If AUKUS were to be cancelled, this would be a disastrous outcome for Australia’s submarine capability.

Australia’s foreign, defence and security policies have traditionally emphasised the role of alliances, partnerships and security institutions to enhance and extend the influence of mid-sized states in partnership with their more powerful neighbours, whether through the US alliance or groups like AUKUS, the Quad, Five Power Defence Arrangements or the Trilateral Security Dialogue (Australia, Japan and the US).

While many expect that Trump will be instinctively opposed to these kinds of partnerships, experts predict a lot will come down to how they are sold to him: how well they can be made to align with his agenda and preferences, how they are seen to benefit America, and how they help Trump compete with China.

Of course, a positive response today has no bearing on how he might feel tomorrow or in six months, so the predictable unpredictability of Trump 2.0 ought to give states like Australia pause to consider what other options they may need to pursue, how to prevent entrapment and enhance freedom of action, and where their red lines are.

A renewed focus on alliance management?

While, typically, domestic politics and alliance politics do not intersect in Australia — the alliance remains extremely popular and its value is understood by the public at large, as noted above — this is also a function of the alliance having, in recent years, operated effectively in support of a bilateral relationship with common goals and shared strategic objectives. There have been relatively few rough edges which might draw domestic attention.

Penny Wong has, in some of her early responses to the election of Trump, stressed that Australia needs to be confident in itself, especially in the face of changes expected to be introduced by Trump.

Donald Trump represents one of those rough edges, for many in Australia. Penny Wong has, in some of her early responses to the election of Trump, stressed that Australia needs to be confident in itself, especially in the face of changes expected to be introduced by Trump.

Australia is a significant regional actor in East Asia and the Pacific in its own right, and there is value — domestically and internationally — in asserting its unique perspective; in acting and speaking with its own voice in the region; and demonstrating this to its population at home.

There are many dimensions to what a more confident Australia might look like, but as former Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull has observed, reflecting on his own experience in dealing with Donald Trump in 2017, he respects “strength and directness from other leaders”. While it may be relatively straightforward for Australia to cooperate where it can with the US, the real test will be when it comes to disagreeing where it must. Building domestic support as an Australian leader faced with a US President like Donald Trump needs more than platitudes. “‘Managing through’ a second Trump term will therefore be necessary but not sufficient,” as former senior Australian official Richard Maude has argued.

This is not an idea that emerged purely in response to his election but shows a vision for security cooperation alongside the alliance.

One approach that Australia should build on, and in which it has been investing over recent years, is a deeper and more diverse range of partnerships with other significant Indo-Pacific states. The blossoming relationship with Japan is a key example, whether through the 2022 Reciprocal Access Agreement, Joint Declaration on Security Cooperation, and Critical Minerals Partnership; the newly-announced regular deployment of Japanese Self Defense Forces personnel to northern Australia alongside US Marine Corps counterparts; the down-selection of the Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Upgraded Mogami-class as a contender for the Royal Australian Navy’s new general purpose frigate programme; or the prospect of including Japan in certain AUKUS advanced capabilities projects.

This scale of partnership is likely the exception, not the rule, however. While Australia’s relationship with India has also improved significantly over the past decade, for example through the regular inclusion of Australian Defence Force assets in India’s annual Exercise Malabar alongside the US and Japan; the upgrading of ties to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership; and the establishment of an annual 2+2 foreign and defence ministers dialogue, there is a lower ceiling on the bilateral relationship at this stage.

Notably, the majority of these initiatives were launched or established years before Trump was elected as president. This is not an idea that emerged purely in response to his election but shows a vision for security cooperation alongside the alliance. This is unlikely to be a comfortable journey, but Australia is starting from a strong position from which to assert a confident vision of the region and its role in it.