The PLA’s global rise: How will India respond?

During Indian Prime Minister Modi’s visit to the US, President Trump hailed a “special bond” with India, launching the transformative COMPACT initiative, including a significant military partnership. With tensions simmering along the Line of Actual Control, India navigates a complex geopolitical landscape, balancing military, strategic tech and AI ambitions with both China and the US.

Hosting Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi at the White House on 13 February 2025, US President Donald Trump said that there was “truly a special bond” between the two democracies. The two leaders launched a “transformative” initiative called COMPACT (Catalysing Opportunities for Military Partnership, Accelerated Commerce & Technology) for the 21st Century.

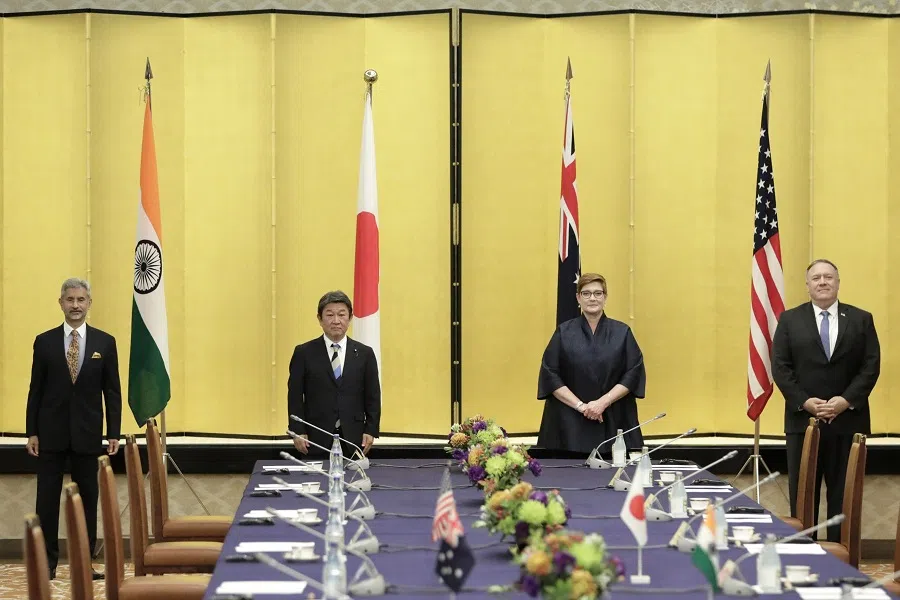

Highlighting the potential US high-tech military sales to India under COMPACT, Trump recalled that in 2017, his previous administration had “revived and reinvigorated the Quad security partnership”. The US-led Quad includes India, Japan and Australia, and he emphasised that it was “crucial to maintain peace, prosperity and tranquillity even in the Indo-Pacific”, not just the Euro-Atlantic.

Significantly, India hosted the Quad’s first high-order war games in 2020, also during Trump’s previous term. Furthermore, the Quad foreign ministers met in Washington on 21 January 2025 soon after Trump became president for the second time. Arguably, he seems to have chosen the Quad as a diplomatic-military coalition that could now deter the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) in the Indo-Pacific.

Initially formed as an official-level security dialogue forum in 2007, mainly at Japan’s initiative, the Quad soon ceased to exist under China’s strong opposition. However, after Trump revived the forum during his first term as president and his successor Joe Biden sustained it, Beijing now sees the Quad as a nascent anti-PLA military clique.

Trump-led Quad ‘warns’ the globalising PLA

The Quad foreign ministers, for their part, agreed, at their latest meeting, to “strongly oppose any unilateral actions that seek to change the status quo by force or coercion”. This is a much-understood “warning” to the globalising PLA.

New US Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s focus on “China’s destabilising actions” may still be reduced by Trump, known for his perceived unpredictability. However, the US recognised the PLA’s globalising image in 2024. Furthermore, the PLA’s stature is evident from the Chinese defence ministry’s comment that “our planet is big enough for both China and the US to “develop individually and collectively”. The idea of a “collective” development arguably reflects Beijing’s concealed aspiration for a US-China military Group of Two (G2) under Trump’s new presidency.

Indeed, the success of Chinese “volunteers” against a powerful US in the 1950-53 Korean War has already shown the PLA to be a competent fighting force. But the PLA’s current “lack of real-world combat experience”, since the Sino-Vietnamese conflict of 1979, is seen by the US as a chink in China’s armour.

My inference from interactions with Chinese and Indian civil and military officials is that Beijing and Delhi pursue mutually exclusive notions of a secure and defensible boundary.

The PLA in Tibet: A thorn in India’s side

Mutual Sino-Indian “trust” during the Korean War, as described by one-time Chinese Acting Foreign Minister Han Nianlong, was lost by the late-1950s. Competitive nationalism ultimately trumped the two countries’ initial Asian fraternity, culminating in their 1962 border war.

Before the Korean War itself, revolutionary Mao Zedong had ordered the PLA to liberate feudal Tibet (Xizang) and annex it to become part of “New China”. Mao’s policy towards Tibet, which borders northern India, gave the PLA opportunities to shape what was to become its enduring military stake in Beijing’s ties with Delhi. Veteran Sinologist John Garver wrote that “as the PLA marshalled to move into Tibet in 1949-1950, Indian leaders feared that Tibet would become, for the first time in history, a platform for Chinese military power”. This ended up happening; India, relatively weaker, did not attempt to stop the PLA in its Tibetan tracks.

The PLA’s success in fulfilling Mao’s agenda in Tibet by 1959 resulted in the unique emergence of a Sino-Indian frontier, also for the first time in history. But this boundary remains unsettled, with its coordinates disputed by the two countries which contest the geography of historical Tibet. My inference from interactions with Chinese and Indian civil and military officials is that Beijing and Delhi pursue mutually exclusive notions of a secure and defensible boundary.

Two aspects of the PLA’s foray into Tibet in the 1950s stand out. First, Delhi wanted to “avoid the stationing of Chinese troops on Tibet’s [traditional] southern border”, India’s northern border. This did not happen; according to India’s former Foreign Secretary Nirupama Rao, in 1951 Tibet agreed, albeit controversially, that it would “actively assist the People’s Liberation Army to enter Tibet and consolidate the [Chinese] national defences” against India. This was Clause 2 of the 1951 Agreement between the “local” Tibetan Government and the “central government” of China in the context of the latter’s historical claims over Tibet. The accord was later repudiated by the Tibetan leader, the 14th Dalai Lama.

The second and more important aspect was the PLA’s influence over China’s India policy. Citing scholar Dai Chaowu, Rao also wrote that a September 1959 PLA intelligence report made a “core suggestion”. Under it, India could propose its acceptance of China’s latent strategic presence in Aksai Chin (at the south-western edge of the Tibetan plateau) in the then-new Sino-Indian western sector. Beijing could reciprocate by accepting India’s presence in Arunachal Pradesh in the east. India disagreed, claiming historical sovereignty over both these areas.

India had retained its British-Raj legacy of Arunachal (“Zang Nan” or “Southern Tibet”) while the PLA was busy annexing Tibet (Xizang) with “New China” in the 1950s. China’s subsequent claim over Arunachal was due to its ideal location for making strategic inroads into India. Aksai Chin, which connects the Chinese provinces of Xinjiang and Xizang (Tibet), could also serve as a launching pad for the PLA to link with China’s protégé Pakistan.

In talks with India, the PLA has played both a hawk and dove, depending on the shifting global geopolitical winds.

The line of contested control

In the 1962 Sino-Indian War, the PLA captured Arunachal but withdrew from there. At that time, Delhi’s belated request for US military help against China was widely believed to have forced Mao to give up some of the PLA’s war gains. A revisionist Indian view now is that the PLA’s withdrawal from Arunachal proved that China never had valid claims over that area. The withdrawal was also foreshadowed in the PLA’s 1959 proposal to barter Arunachal for Aksai Chin.

Nonetheless, the PLA, whose foray into Tibet created a de facto Sino-Indian frontier, has so far remained as China’s expeditionary force along a bilateral Line of Actual Control (LAC). Significantly, in 1993, with China in search of allies following Western criticism of the Tiananmen incident, India proposed an accord on maintaining “peace and tranquillity” along the LAC. While China’s civilian leadership agreed, the PLA was “insistent” on its own configuration of the LAC. With this issue postponed in 1993, the PLA continues to assert its claims regarding the LAC which has therefore become a line of Sino-Indian contention.

The Sino-Indian clash at Galwan in the western sector in mid-2020 caused much international concern and led to a flurry of bilateral military- and civilian-level negotiations. In talks with India, the PLA has played both a hawk and dove, depending on the shifting global geopolitical winds.

India’s AI ambitions amid China tensions

A new geopolitical concern for India is Beijing’s potential bid for one of two G2 options with either Russia or even the US on the Chinese “win-win” terms. These options concern India because of its own strategic ties with Russia and the latest Trump-Modi launch of the US-India initiative TRUST (“Transforming the Relationship Utilising Strategic Technology”). This initiative will “promote [bilateral] application of critical and emerging technologies” in areas ranging from defence and artificial intelligence to energy and outer space.

India had wanted to catch up with China even earlier, especially in the military applications of artificial intelligence.

In 2023, senior PLA officer Zhao Xiaozhuo stated that India’s limited indigenous defence industry poses no military threat to China. Another Chinese narrative suggests that India cannot decouple its economy from China’s due to its reliance on cost-effective Chinese high-tech investments. This perception, shared by some in India, is seen as Delhi’s reason for pursuing peaceful relations with Beijing. However, the situation is more complex, as India’s strategic assets, including its “nuclear triad”, are of indigenous origin.

In March 2024, Chinese President Xi Jinping identified high tech, including AI, as key to the PLA’s modernisation. In the PLA’s strategic playbook, China should become a well-armed good cop globally, in contrast to the US, which is already an over-armed bad cop.

In this ambience, India is also seeking a niche role in both the civil and military realms of AI. On international civil AI cooperation, Modi and French President Emmanuel Macron co-chaired an “AI Action Summit” in Paris on 11 February 2025. Two days later, Modi and Trump launched the US-India strategic tech initiative, TRUST inclusive of AI, in Washington.

India had wanted to catch up with China even earlier, especially in the military applications of artificial intelligence. The PLA could thus use its conventional and high-tech skills to influence Beijing’s policy towards Delhi, a US “strategic partner”, in the emerging geopolitics of Trump’s renewed presidency.