Is India warming up to Chinese investment?

China’s investments in India, historically underwhelming, have dropped further with India’s fears of China’s “opportunistic takeovers”, says Indian researcher Amit Kumar. But a more favourable Indian public discourse towards Chinese investments and the potential for win-win benefits could turn things around.

On 21 October, India and China reached a deal to disengage troops in Depsang and Demchok — the two remaining friction points in Eastern Ladakh along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) — thereby concluding the disengagement process on all the friction points in the four-and-a-half-year-long standoff between the two armies.

Throughout the duration of this standoff that began in May 2020, Beijing maintained that the boundary issue must not be allowed to derail the overall development of India-China relations. New Delhi, on the contrary, contended that peace and tranquillity on the LAC are essential to realising progress in other domains.

However, the recent breakthrough in the negotiations has generated speculation around the plausible reevaluation of the broader economic relations between the two countries, particularly in the domain of Chinese investments in India.

From bad to worse?

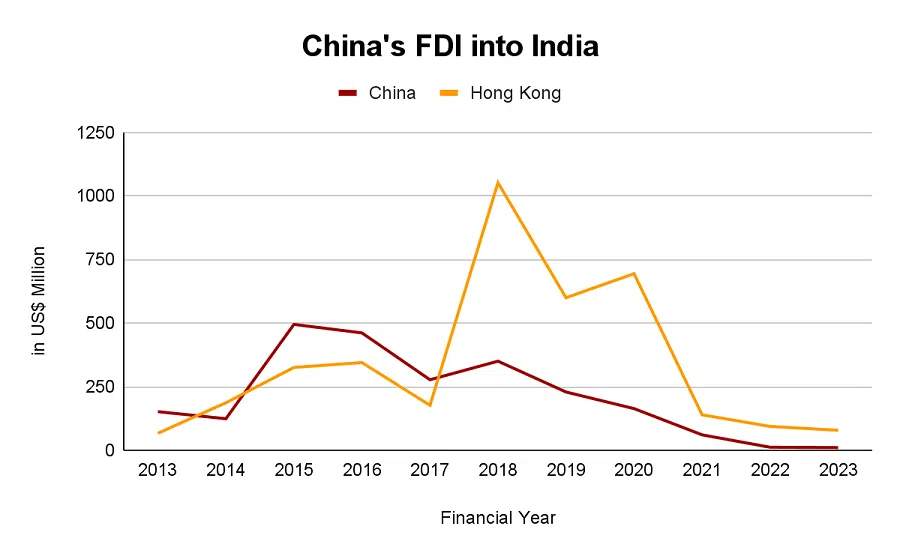

It is worth highlighting that Chinese investments in India have historically been quite underwhelming. India’s official figures show that China’s cumulative foreign direct investment (FDI) from 2000-2020 amounted to a mere US$2.4 billion. If investments from Hong Kong are included, it totalled another US$4.7 billion between 2000-2023.

Until the end of the first quarter of 2024, Chinese FDI in India totalled just US$7.4 million. Not surprisingly, investments from Hong Kong witnessed a similar trend.

According to China’s Ministry of Commerce, cumulative investment (exclusive of Hong Kong) in India by the end of 2021 amounted to US$5.4 billion. Even by Chinese accounts, the investments appear abysmally low.

Most of these investments have been concentrated in sectors like infrastructure, energy, automobiles, consumer goods, real estate, pharmaceuticals and e-commerce. However, an absence of any sector-wise data on investment from Chinese enterprises by either of the two governments, hinders a detailed analysis.

Nevertheless, the Indian government’s FDI data indicates a boom between 2015-2018. The period witnessed a spike in investments from Chinese tech players like Alibaba and Tencent. Several Indian startup tech companies raised funding from Chinese venture capitalists, allowing the latter to acquire minority or controlling stakes in Indian firms. But 2020 marked a watershed moment.

While the FDI from China in the period 2013-19 averaged around US$298 million, the same dropped to US$61 million between 2020-23. In the last three years, FDI inflows from China amounted to US$11.6 million (2021), US$9.9 million (2022), and US$42 million (2023). Until the end of the first quarter of 2024, Chinese FDI in India totalled just US$7.4 million. Not surprisingly, investments from Hong Kong witnessed a similar trend.

Perceived threat from China

However, it was not the crisis in Ladakh that escalated this drastic transformation. India’s insecurity vis-à-vis Chinese investment was piqued during the pandemic in April 2020 when it learned that China’s central bank, the People’s Bank of China, acquired over 1% stake in HDFC (India’s biggest bank by market capitalisation) when its prices were trading low. The news sent shockwaves across ministries in India, springing them into action.

This perceived threat of “opportunistic takeovers” of Indian businesses by Chinese companies led the Indian government to unveil Press Note 3 in April 2020 to amend the FDI policy involving all countries sharing a land border with India. Ostensibly aimed at China, it subjected all FDI from such territories to government approval. Furthermore, the “transfer of ownership of any existing or future FDI in an entity in India, directly or indirectly, resulting in the beneficial ownership” of entities situated in such countries was also made subject to government approval.

The standoff in Ladakh and the clashes in Galwan only strengthened India’s resolve to curb inbound Chinese investments. New Delhi’s response was as much a part of the retaliation as it was a result of its suspicion.

The Indian public discourse has lately witnessed a softening in attitude vis-à-vis Chinese investments. There is a growing recognition of the need to balance security concerns with developmental goals.

Consequently, based on available data, between FY21 (2020-21) and FY23 (2022-23), the Indian government rejected 58 Chinese FDI applications. Of these, ten were rejected in FY21, while FY22 and FY23 saw 33 and 15 rejections, respectively. These included one-billion-dollar investment proposals each by Chinese giants such as BYD and Great Wall Motors.

Balancing security concerns with developmental goals

The Indian public discourse has lately witnessed a softening in attitude vis-à-vis Chinese investments. There is a growing recognition of the need to balance security concerns with developmental goals. While it deems it necessary to exclude Chinese enterprises from participating in sensitive and strategic sectors, it disapproves of shutting the non-strategic sectors to inbound Chinese investments.

The complementarities between the two economies further create an opportunity to reimagine the relationship. The Chinese economy is experiencing over-investment, which has led to the problem of overcapacity at home. As a result, cheap Chinese commodities have flooded external markets, hollowing out their domestic manufacturing base. The West, particularly the US and the EU, has resolved to hit back at these Chinese commodities. In October this year, the EU imposed tariffs ranging from 17-35% on EVs made in China. US President-elect Donald Trump, has vowed to impose 60% tariffs on all Chinese goods.

Some have suggested that China scale up its outbound investment as its exports become unpopular with the policymakers in the West. Compared to imported goods, investments from China are far less controversial.

India, on the other hand, has been encouraging inbound investments to boost its share of manufacturing in the economy from the current 13% to 25% of the GDP. Additionally, an influx of imports from China has been a contentious issue for India. As the asymmetry in bilateral trade has grown, India’s trade deficit vis-a-vis China has ballooned from a mere US$0.19 billion in 2001 to over UD$100 billion in 2023. However, Chinese investment in India has not kept pace with increasing demand for its goods.

India offers Chinese enterprises a lucrative investment destination with a large market. Furthermore, their India operations are unlikely to invite the same tariffs as their operations in China.

A meeting point?

Here lies the meeting point for the two countries. Chinese investment can help reduce India’s widening trade deficit vis-à-vis China and enable its integration with the global supply chains. On the other hand, India offers Chinese enterprises a lucrative investment destination with a large market. Furthermore, their India operations are unlikely to invite the same tariffs as their operations in China.

On its part, China would do well to explore real opportunities beyond venture capital investments and contracting in India. As a quid pro quo, New Delhi must offer greater clarity (possibly through a negative list) on sectors it regards as sensitive to Chinese presence while leaving the remaining sectors open to inbound investment.