With us or invisible: The dangerous simplicity of America’s Asia policy

At his maiden Shangri-La Dialogue outing, the US defence secretary laid out a stark and demanding vision for the region’s security. ASEAN and much of Southeast Asia did not feature in it.

At his inaugural appearance at last week’s 2025 Shangri-La Dialogue (SLD), US Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth delivered an unvarnished message centred on hard power, that is, “deterrence by denial” against China, which he cast explicitly as the US’s foremost threat.

Hegseth said US President Donald Trump’s administration is steering US defence policy “back to basics”, anchored in what he called “common sense”. Do these “basics” make common sense to this region, where strategic nuance and cooperative security are part of the landscape?

Back to basics

The foremost “back-to-basics” message from Hegseth’s speech is that every nation must first take care of its own defence. For the US under Trump, this translates into a hard-edged focus on securing the US homeland against illegal migrants at its borders or geopolitical adversaries across oceans.

It signals a resolute “America First” ethos: American strength must be built for America and from within America. Hence, the urgency of reviving its defence industry, and the redeployment of US Coast Guard cutters from Asia to address immigration challenges at its southern border.

Such inward prioritisation reverberates abroad. US shipyards, already struggling to meet domestic demand, might have to delay deliveries of Virginia-class submarines to Australia under the AUKUS agreement.

It was in this spirit that Hegseth called on these countries to raise their defence spending to 5% of gross domestic product (GDP).

Call to action

Hegseth confronted US allies with a sobering truth: the US will not defend you if you do not first defend yourself. This stance is a hallmark of Trump’s foreign policy, which resonates with international relations scholar Waltz’s classic self-help principle in an anarchic international system.

Europe has been the most prominent target of this approach, but it extends equally to Asia. The US’s security guarantees to its Asian allies are now conditioned on the latter’s proactive, enhanced investment in their capabilities to act as “force multipliers”, not “dependents” on American protection. This is a decisive shift towards a more reciprocal and pragmatic alliance model.

It was in this spirit that Hegseth called on these countries to raise their defence spending to 5% of gross domestic product (GDP). His message was directed at a select circle of like-minded states: those already primed to coalesce around Washington in facing down the China challenge. These are the US’s formal allies — Japan, Australia, the Philippines, and South Korea (whose primary threat is North Korea) — as well as India and Taiwan, two close security partners that share the US’s perception of a China threat. These countries are most strategically aligned and already embedded in an expanding web of joint military activities and interoperability with Washington.

The US’s intent has been advanced through concrete demands and deployments. At the SLD, Hegseth pushed Australia to lift its defence spending, reportedly from 2-3% of its GDP. In Japan in March, he announced the upgrading of US Forces Japan into a “war-fighting headquarters” to enhance joint operational capabilities with Japan’s Self-Defence Forces. In the Philippines, he announced the forward deployment of advanced US systems, including the NMESIS anti-ship missile platform in the Batanes, which lie within striking range of Taiwan. With the same logic, Hegseth signalled the re-securitisation of the Quad, as reflected in the launch of the Indo-Pacific Logistics Network and the emerging focus on forging a collective defence industrial base between the US and other Quad countries.

Few countries in the region view China in purely adversarial terms, let alone consider it the singular driver of their defence postures.

Different ideas of China

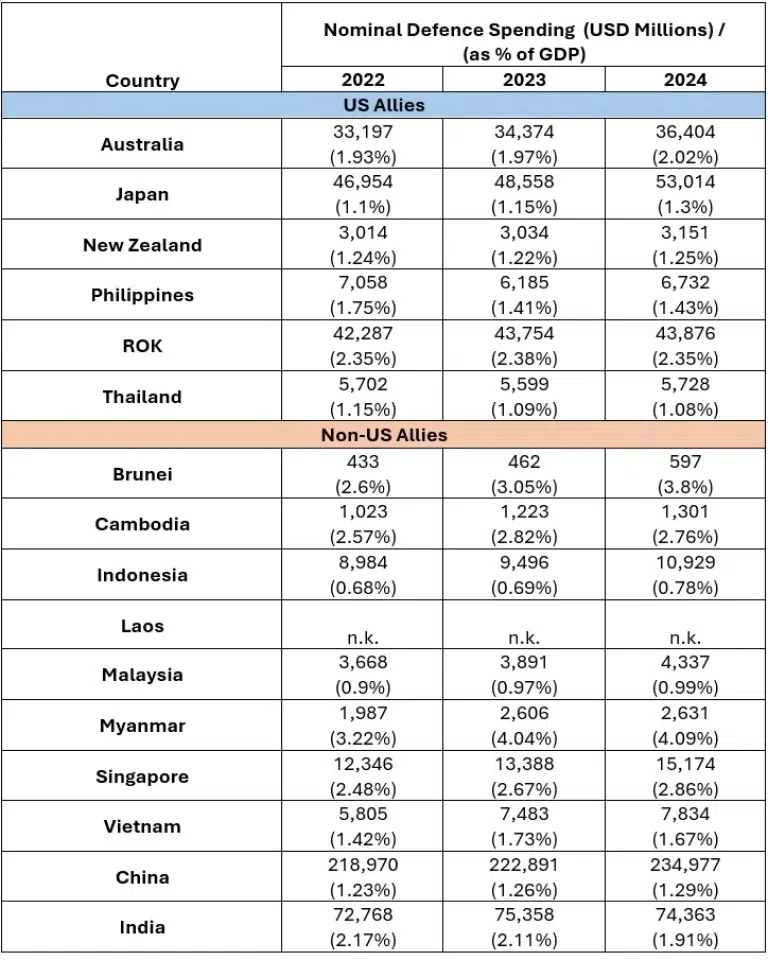

This “5%” call is a stark, implausible demand for most US allies and partners in the region. Currently, Asian countries allocate 1-3% of their GDP to defence (Table 1), constrained by fiscal limits and the need to prioritise socio-economic development.

In Southeast Asia, the challenge is not merely one of limited capacities but more fundamentally of divergent strategic cultures and threat perceptions. Few countries in the region view China in purely adversarial terms, let alone consider it the singular driver of their defence postures.

Southeast Asian claimant states in the South China Sea — particularly the Philippines and Vietnam — may stand out for a sharper sense of threat arising from Chinese maritime encroachments, yet even they do not define China solely as a threat.

Throughout his speech, Hegseth mainly spoke the language of force, of the “warrior’s ethos”, deterrence, and preparation for war should deterrence fail. At a side meeting with Southeast Asian defence leaders, he offered some rhetoric about the US supporting ASEAN centrality and engaging the ASEAN defence tracks.

... the Philippines, whose alignment with US strategic aims vis-à-vis China makes it the lone Southeast Asian country to emerge from Hegseth’s narrative with some visibility, while the rest were consigned to the margins of a stark binary...

However, his central message at the SLD was unequivocal: the US’s staying power in Asia would be defined overwhelmingly by the imperative to build and project capabilities needed to deter and, if necessary, to defeat China.

Allies or irrelevant?

He did provide much-needed reassurance that the US is “not reckless” and does not seek war with China, but this posture rests on superior capabilities, that is, “peace through strength”. It cares little for diplomacy, trust-building, and the shared stewardship of peace through inclusive regional mechanisms that ASEAN champions.

In this worldview, ASEAN is absent and much of Southeast Asia is rendered almost irrelevant, except for the US’s ally, the Philippines, whose alignment with US strategic aims vis-à-vis China makes it the lone Southeast Asian country to emerge from Hegseth’s narrative with some visibility, while the rest were consigned to the margins of a stark binary: those willing and able to stand with the US against China, versus those who do not matter in Washington’s strategic design.

“America First is not America Alone”, Hegseth declared, but the resulting logic of his binary framing is this: in Asia, America stands only with a select few, if not alone.

This article was first published in Fulcrum, ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute’s blogsite.