US suspension of foreign aid: Will China fill the void?

As the US shuts down its supply of foreign assistance, some Southeast Asian countries are looking at China to fill the gap. But given China’s different approach to aid, it cannot step in as a direct substitute for America.

President Donald Trump’s shock decision to shut down the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and halt billions of US foreign assistance has jeopardised US-funded development programmes worldwide. As US aid comes to a crashing halt and with it, an important means to advance US soft power, the question is whether Southeast Asian countries can look to China to fill this gap.

Pragmatic China

This prospect is far from certain. China has a different approach to aid. According to the Lowy Institute’s Southeast Asia Aid Map, Beijing prioritises loans over grants, emphasises hard infrastructure over human capital and institutional capacity, and tends to fall short of fulfilling pledged assistance. The Lowy Institute’s dataset covers Official Development Assistance (ODA) and Other Official Flows (OOF) to the region between 2015 and 2022.

This conceptualisation prioritises pragmatism over altruism, with a reciprocal — and at times transactional — dynamic.

In the past decade, China has bolstered its role as a global development actor, establishing the China International Development Cooperation Agency (CIDCA), launching the Global Development Initiative, and increasing its contributions to multilateral development institutions. Yet, as China considers itself a developing nation, its development cooperation is framed as south-south “mutual assistance” rather than a north-south donor-recipient relationship. This conceptualisation prioritises pragmatism over altruism, with a reciprocal — and at times transactional — dynamic.

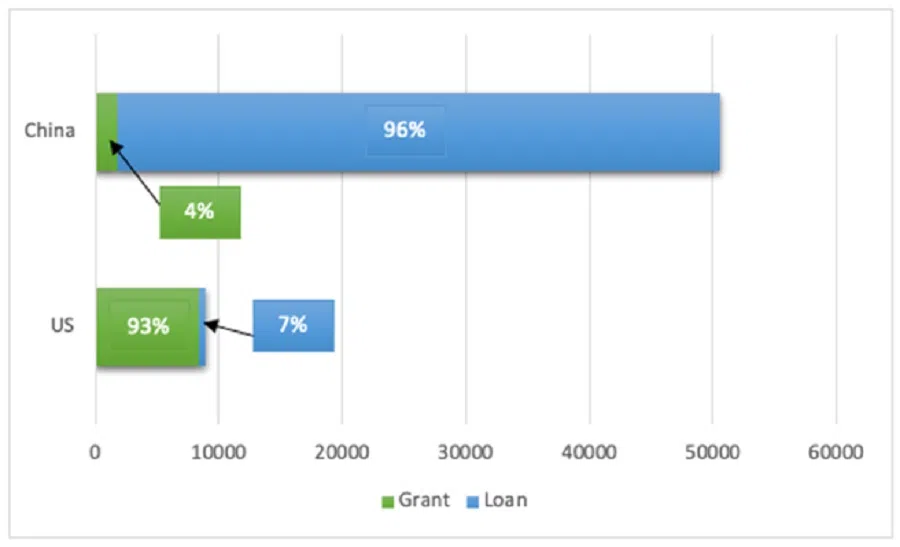

From 2015 to 2022, China’s total aid to Southeast Asia amounted to US$50.5 billion, outweighing the US’s US$8.9 billion. Yet, this amount has been overwhelmingly loan-based, with US$48.7 billion in loans versus the US’s US$597 million. In grants, China lagged far behind, providing US$1.8 billion, less than a quarter of the US’s US$8.3 billion. Loans constituted 96% of China’s aid to the region, while grants made up only 4%. The US model was the opposite, with 93% in grants and 7% in loans (Figure 1).

China’s aid to Southeast Asia heavily prioritised the economy and hard infrastructure...

China leads on aid

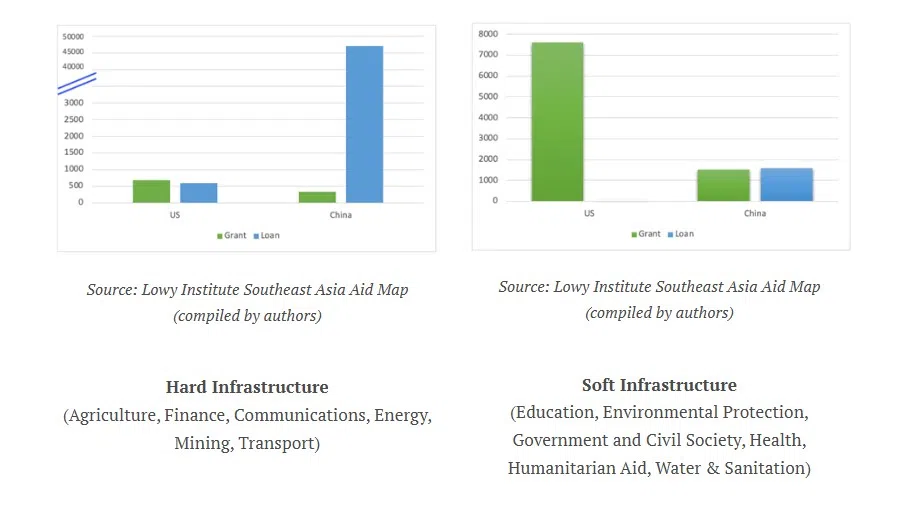

China’s aid to Southeast Asia heavily prioritised the economy and hard infrastructure, as reflected in the dataset’s six sectors of agriculture, finance, communications, energy, mining, and transport. China disbursed US$47.1 billion in these sectors — almost entirely in loans — accounting for 94% of its total aid to the region in the period. This was nearly eight times the US’s US$597 million. However, US grants in these sectors, totalling US$685 million, was more than double China’s US$333 million (Figure 2).

In contrast, the US’s aid prioritised soft infrastructure, focusing on human capital, good governance, and grassroots empowerment across six sectors – education, environmental protection, government & civil society, health, humanitarian aid, and water and sanitation. Its grants in these sectors totalled US$7.6 billion — more than five times China’s US$1.5 billion. This reflected US commitment to capacity-building, sustainable development, public health and uplifting of vulnerable groups, with a view to fostering long-term social, community and institutional resilience. Meanwhile, China provided US$1.6 billion in loans for these sectors, following its preference for loan-based financing.

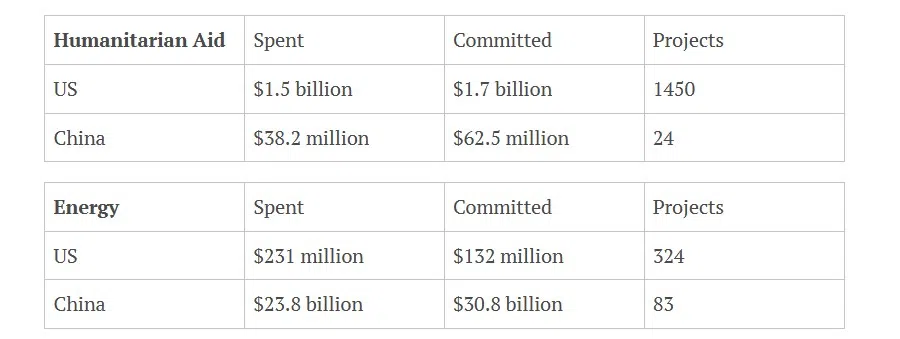

The US’s leadership in humanitarian assistance, contrasted with China’s primary focus on energy, highlights their differing priorities in development cooperation with the region.

US leads on soft infrastructure

The US’s leadership in humanitarian assistance, contrasted with China’s primary focus on energy, highlights their differing priorities in development cooperation with the region (Table 1).

China’s energy aid, at US$23.8 billion, accounted for half of China’s hard infrastructure aid to the region. Its energy aid comprised primarily loans for large-scale projects such as power stations, transmission lines, pipelines, and power plants. US aid in this sector was a fraction of China’s, at US$231 million, focusing on technical assistance, regulatory reforms, and renewables. This aligned with its emphasis on institutional capacity-building and sustainable development.

Meanwhile, the US took a commanding lead in humanitarian aid, providing US$1.5 billion, compared to China’s US$38.2 million. This disparity highlights that China’s development cooperation takes a much more pragmatic approach, where aid serves as an extension of economic cooperation, emphasising mutual benefit over unilateral assistance. China’s model aligns more with “development financing” whereas US aid fits the traditional definition of “development assistance”.

China’s aid disbursement was unevenly distributed and appears strategically aligned with its foreign policy objectives, with higher disbursement rates in geopolitically prioritised or aligned countries...

China’s strategic aid

Of note, China’s aid to the region between 2015 and 2022 saw a relatively low actualisation rate. Of the US$132 billion committed, only US$50.5 billion – just 44% – was disbursed. In contrast, the US disbursed US$8.9 billion of its US$9.5 billion commitment (85%).

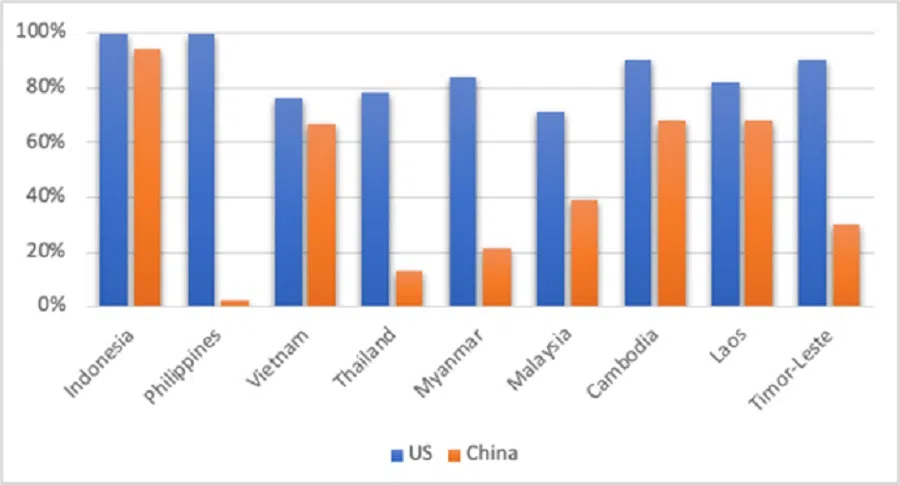

China’s aid disbursement was unevenly distributed and appears strategically aligned with its foreign policy objectives, with higher disbursement rates in geopolitically prioritised or aligned countries: Indonesia led at 94%, followed by Cambodia and Laos at 68%, and Vietnam at 67%. The Philippines ranked last at 2%, illustrating Beijing’s failure to fulfill its pledge to support then President Duterte’s “Build Build Build” agenda.

In contrast, the US maintained consistently high actualisation rates across the board, regardless of political alignment, with Myanmar and Cambodia at 84% and 90%, respectively (Figure 3).

US more reliable in disbursing promised aid

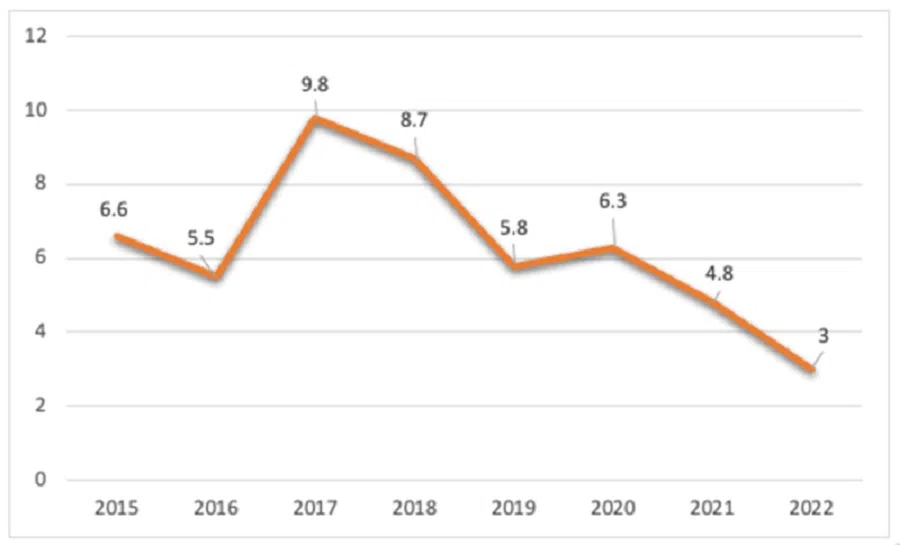

Lastly, China’s overseas development financing has been declining globally, peaking in 2016 after the surge associated with the roll-out of the Belt and Road Initiative in 2013. Reflecting this trend, its aid to Southeast Asia peaked in 2017 and has since been on a downward trajectory (Figure 4). With its current economic challenges, the expectation that China will readily fill the gap left by the American aid withdrawal is even far less guaranteed.

Capabilities and political willingness aside, the stark differences in the two countries’ approaches to aid mean that China cannot simply step in as a direct substitute for America. China’s development cooperation is rooted in pragmatism, serving as an extension of its domestic economic strategy, unlike the US’s focus on human capital, institutional capacity and local community well-being. However, there is room for evolution.

To strengthen its credibility as a development partner, China could improve the fulfilment of it pledges and focus more on human resource development and local community welfare, alongside its signature investments in roads, bridges, and pipelines. This would go a long way in winning the hearts and minds of Southeast Asians.

This article was first published in Fulcrum, ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute’s blogsite.