China moves to raise retirement age to bolster workforce, ease pension pressure

As China grapples with a rapidly ageing population, the delay in retirement — a decade-long initiative — is nearing reality.

(By Caixin journalists Zhou Xinda, Xu Wen, Tang Yanyu, Jiang Moting, Cui Xiaotian, Huang Huizhao and Han Wei)

After more than a decade as a recurring tea-time conversation topic, the delay in retirement is nearing reality in China, set to impact over 500 million workers as the country grapples with a rapidly ageing population.

The five-year reform blueprint, released last month following a key Communist Party gathering, includes a commitment to raise the retirement age. According to the resolution adopted at the third plenum of the party’s 20th Central Committee, China will gradually increase the statutory retirement age based on the principle of “voluntary participation with appropriate flexibility”.

For the first time, a key policy document outlines the principles of the reform, fuelling expectations that the decade-long initiative will soon be implemented.

China’s current minimum retirement age to receive pension benefits — 60 for men and between 50 and 55 for women, depending on their job — is among the lowest globally. In comparison, the retirement age is 62 for men and women in the US and 66 in Germany.

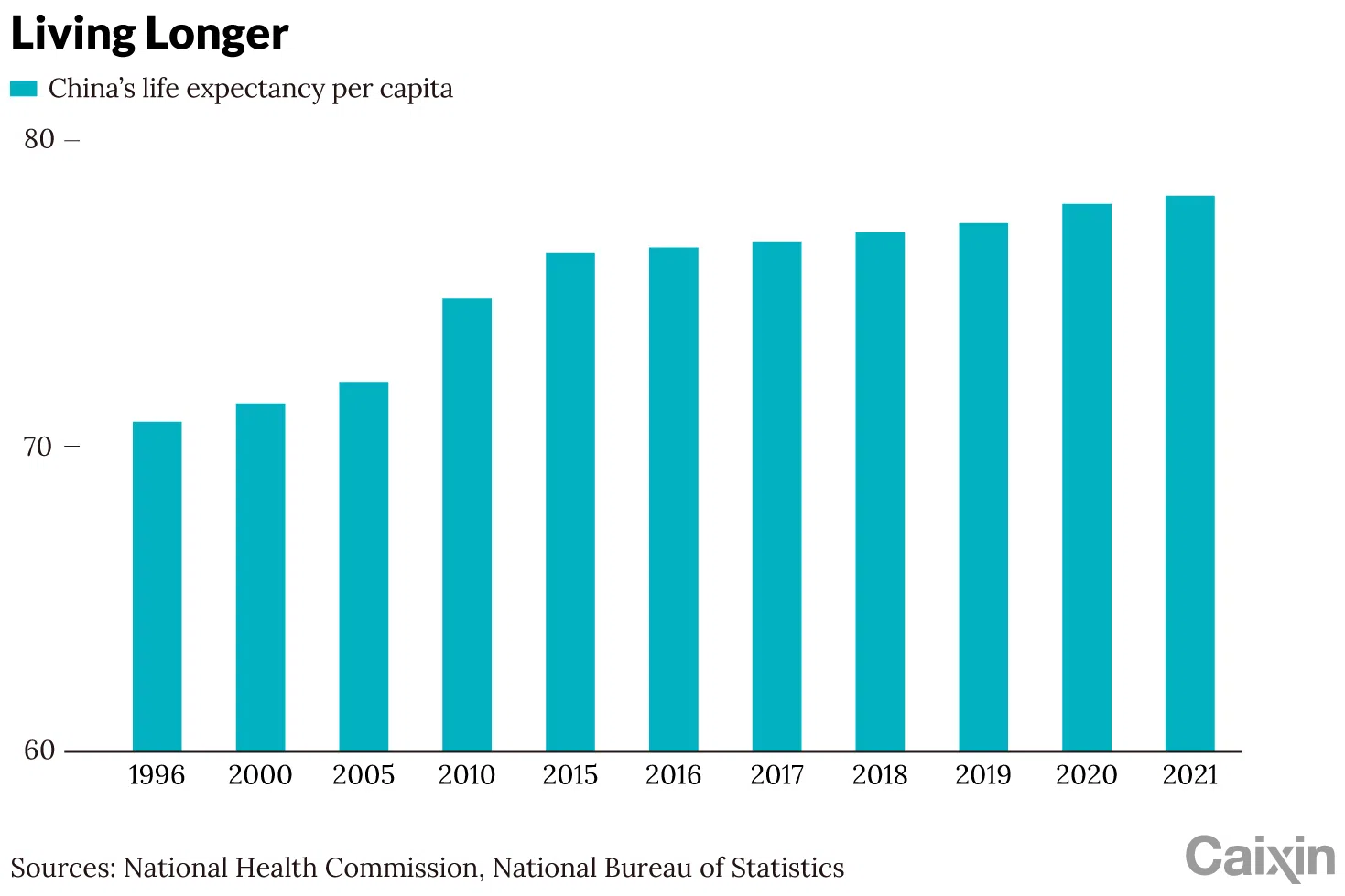

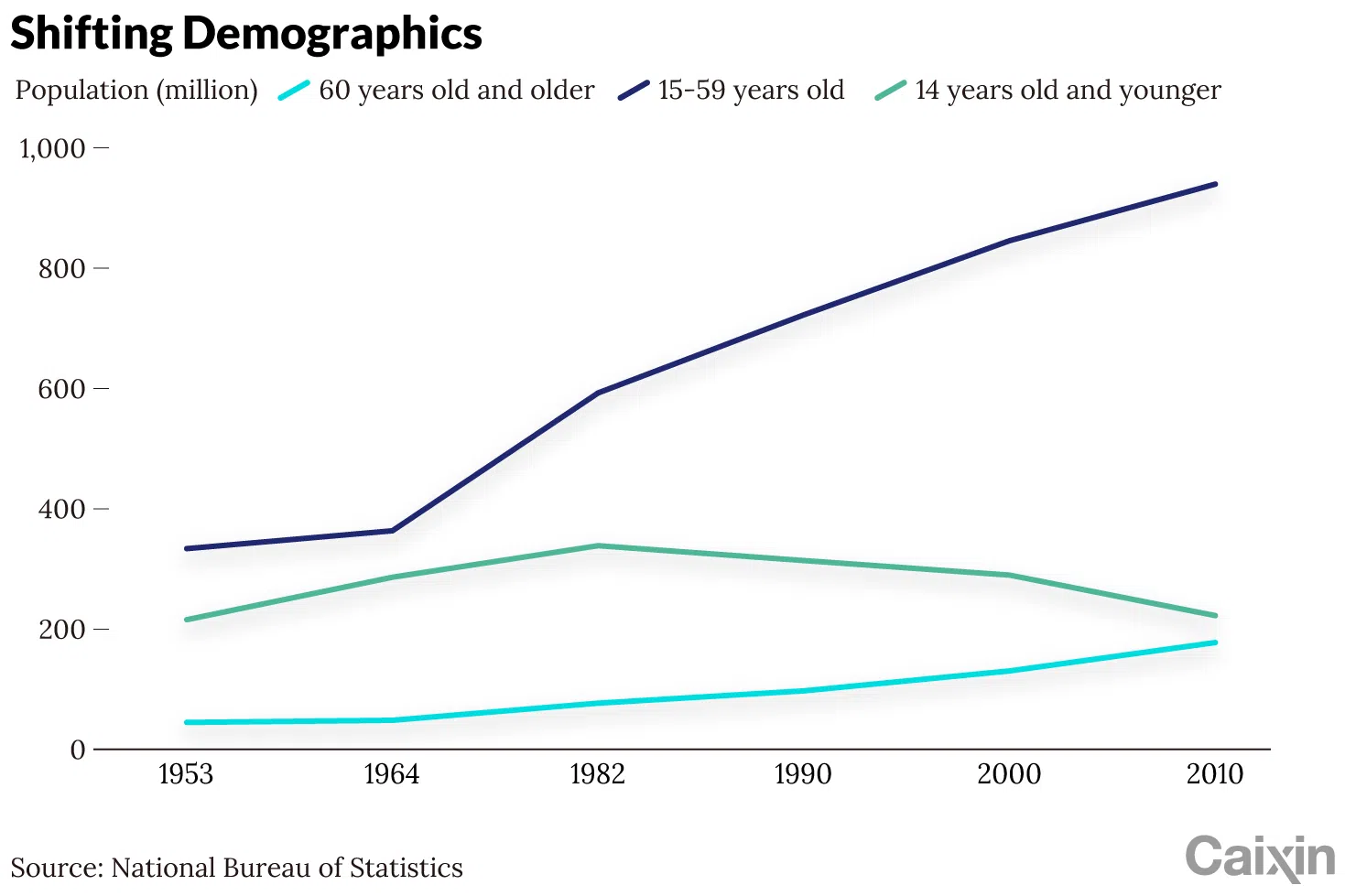

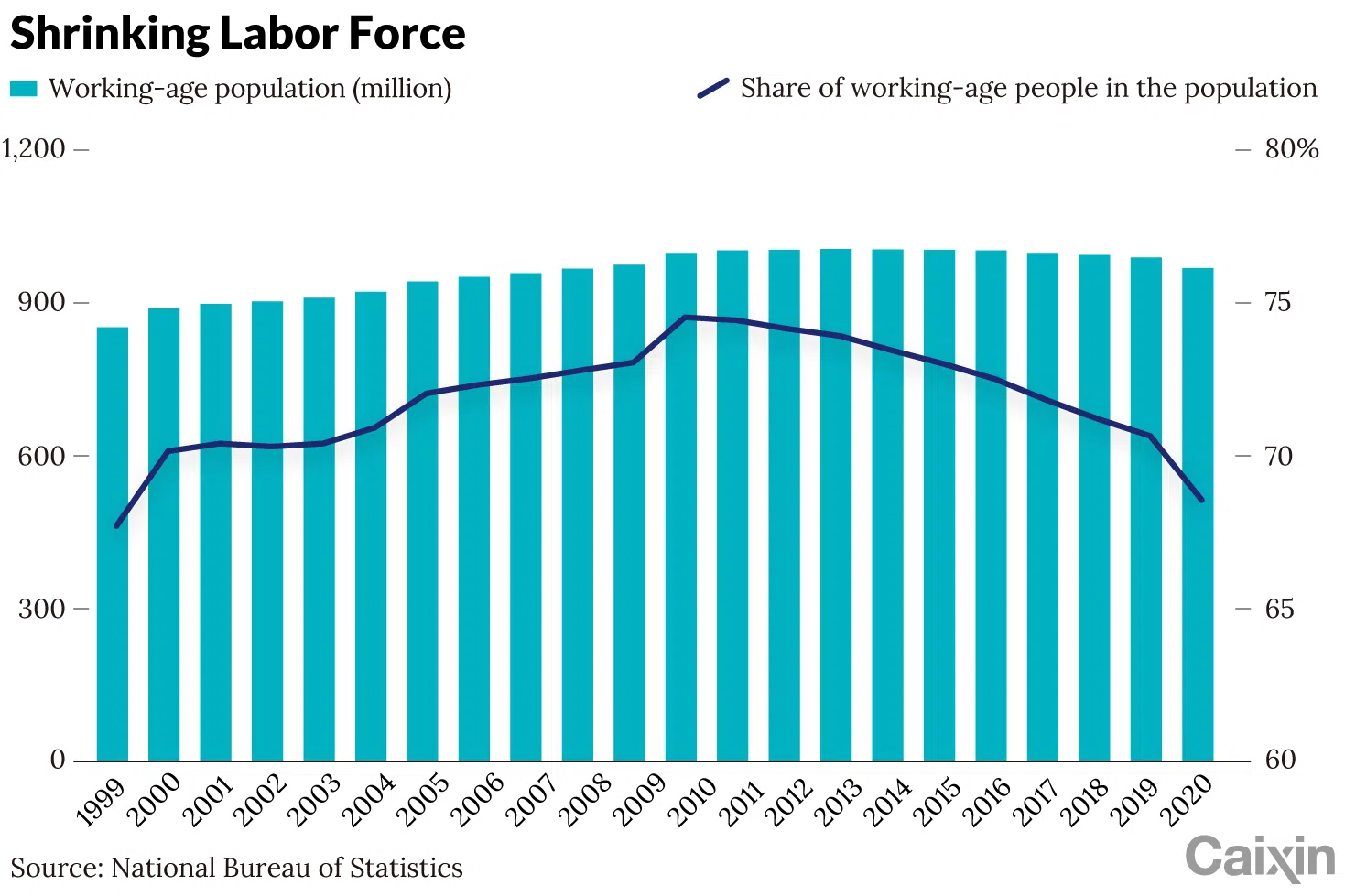

While retirement rules have remained unchanged since 1951, China’s average life expectancy has increased from 67.9 years in 1981 to 78.2 years in 2021. Meanwhile, the world’s second most populous country is experiencing an unprecedented demographic shift. The number of people aged 60 and older has risen from 126 million in 2000 to 297 million in 2023, doubling their share of the population. According to the International Monetary Fund, the number of working-age Chinese, those who are 15 to 64, will shrink by about 170 million over the next 30 years, while the 65 and over population will surge to nearly 380 million, marking China as a “severely ageing” society.

From 2012 to 2021, the dependency ratio for the elderly — persons 65 and over — rose from 12.7% to 20.8%, meaning that every 100 workers had about 21 elderly people to support in 2021...

Exacerbating the situation is the nation’s declining birth rate. The number of newborns has continuously declined since 2017, leading to a shrinking population in 2022. In 2023, the number of births fell to a record low of 9.02 million as India passed China as the world’s most populous country.

The dual challenges of ageing and declining birth rates are profoundly impacting the economy and burdening the social security system. From 2012 to 2021, the dependency ratio for the elderly — persons 65 and over — rose from 12.7% to 20.8%, meaning that every 100 workers had about 21 elderly people to support in 2021, reflecting the growing pressure on the working-age population.

This raises concerns about the sustainability of China’s pension funds. Several research institutions estimate that the country’s basic pension funds, which cover urban employees, will run out in about a decade.

One feasible solution to address these challenges is to delay retirement. Scholars have suggested that pushing back the retirement age is not only an important step to alleviate pension burdens, but will more importantly expand labour force participation and optimise the allocation of human resources.

For delayed retirement to be implemented smoothly, it requires coordination with industrial, fertility support and healthcare policies. Ultimately, the solution must address the challenges of an ageing and low birthrate population by providing comprehensive support for families and individuals, and creating a social environment that better adapts to the new demographic structure, experts say.

Ten years in the making

In 2013, Chinese policymakers first proposed raising the retirement age “in progressive steps”, but authorities have never spelled out details.

In March 2015, then Minister of Human Resources and Social Security (MHRSS) Yin Weimin said that the delayed retirement plan would be formulated that year. “We will first announce the plan, but its implementation will take at least five years,” he said.

However, no concrete progress was made until October 2020, when delayed retirement was included in the reform agenda of China’s 14th Five-Year Plan for the 2021 to 2025 period.

A person close to the MHRSS told Caixin that accelerating the implementation of reforms was emphasised again at an internal meeting in 2023.

Analysts warn that extending the retirement age may only weaken job opportunities for young people.

The slow rollout partly reflects regulators’ concerns about the potential impact on the job market. China’s youth unemployment rate has remained high since the pandemic. Despite a gradual decline this year, the jobless rate for 16- to 24-year-olds was 13.2% in June. Analysts warn that extending the retirement age may only weaken job opportunities for young people.

But as the population ages and birth rate declines, extending retirement has become an increasingly pressing issue. Between 2012 and 2021, China’s working-age population fell from 1.006 billion to 949 million, a drop of more than seven million people per year, according to Tong Yufen, a professor at the Capital University of Economics and Business in Beijing. With the declining birth rate, the “younger elderly” group will be crucial for addressing future labour shortages, he said.

Experts are calling for the reform plan to be announced as soon as possible. The window of opportunity is narrowing and the longer the delay in putting retirement reforms in place, the harder it will be to make the changes, one expert said.

“The specifics of the plan are not that important at this moment,” said Dong Dengxin, director of the Finance and Securities Institute at Wuhan University of Science and Technology. “What matters now is to disclose it as soon as possible to give the public time to adjust their expectations,” Dong added

The latest resolution from the third plenum introduces for the first time the principle of “voluntary participation with appropriate flexibility”. Several experts said that it signals that raising the retirement age is about to happen.

Progressive steps

The key is designing a reform plan that balances current pension payment challenges with minimising public resistance. That puts the focus on the pace and extent of the changes.

Making changes “in progressive steps” is the consensus among decision makers and will be the primary approach in future plans.

According to international practices, most countries have extended the retirement age by 1 to 2 months per year until reaching 65 to 67 years, with men and women retiring at the same age. Since January 2012, Germany has planned to raise the retirement age from 65 to 67 over 18 years, extending it by one month per year for the first 12 years and two months per year for the next six years, aiming to reach 67 by 2030. The US has a similar plan, with the retirement age increasing from 66 in 2021 to 67 by 2027.

Change will have a much longer process in China. If the country extends the retirement age by two months each year, it will take at least 30 years for men and 60 years for women to reach the retirement age of 65.

Extending the retirement age by two months a year is somewhat slow given China’s current population age structure. If necessary, a “slow jog” approach should be considered, said another social security policy expert.

Changes are likely to come at a faster pace, according to Fang Lianquan, a senior social welfare expert at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in Beijing. “The pace of delaying retirement depends on the difficulty of implementing the policy,” he said.

Some researchers suggest extending the retirement age by three or four months a year is widely acceptable and would reduce the prolonged timeline.

Over the past decade, pension benefits for different occupational groups have diverged further, complicating reform efforts. According to data from the MHRSS, the average monthly pension payout for rural residents and non-employed urban residents was 204.70 RMB (US$28.56) in 2022, while the payment was 3,148.60 RMB for enterprise retirees and 6,099.80 RMB for government and public institution retirees.

“Delaying retirement must be coordinated with other pension system reforms,” said Nie Riming, a researcher at Shanghai Institute of Finance and Law. “Policies should not simultaneously delay retirement and widen the pension payout gap. And the interests of different groups must be balanced.”

Reforming the retirement age involves the principles of actuarial fairness and incentive neutrality, which require an incentive-compatible mechanism for employment and pension payments, Fang said. A key issue in China’s existing pension policy is the negative incentive that encourages early retirement, as the marginal benefits of longer-term contribution decrease.

The principles of “voluntary” and “flexible” set by the third plenum mean individuals will be able to decide when to retire. After reaching the minimum retirement age, they can choose to retire immediately or delay, with a corresponding system of pension rewards and penalties. In similar arrangements in OECD countries, the average reward rate is between 6% and 8% for each year retirement is deferred.

Fang said reform measures are needed to better reward people who make longer pension contributions. “A key aspect of policy design is finding ways to incentivise workers to work longer, contribute more to social security and choose to delay retirement,” he said.

“Many systemic barriers to elderly employment remain, such as inadequate employment protection, limited information access for older job seekers and a lack of job training for re-employed seniors.” — Professor Lu Jiehua, Department of Sociology, Peking University

Systemic works

Keeping people in the job market longer will require more supportive policies tailored to elderly employees, analysts said.

Lu Jiehua, a sociology professor at Peking University, said many systemic barriers to elderly employment remain, such as inadequate employment protection, limited information access for older job seekers and a lack of job training for re-employed seniors.

As the population ages, both young and elderly job seekers face greater challenges in the job market, said Zhang Chenggang, an associate professor at the School of Labor Economics at Capital University of Economics and Business.

Li Changan, a researcher at the University of International Business and Economics in Beijing, highlighted several deep-rooted issues hindering employment in China. These include relatively low average wages, large income distribution gaps, limited social security coverage, and vast differences in levels of protection. Additionally, there are problems such as excessively long working hours and employment discrimination.

Employment equity is particularly important in the current context, Li said. This requires eliminating various forms of employment discrimination and removing unequal restrictions on workforce mobility, including those based on household registration, gender, age, physical disabilities, algorithmic biases and the digital divide.

“It is necessary to strengthen legislation and increase penalties for employers who engage in employment discrimination,” he said.

Mao Yufei, an associate professor at the School of Labor Economics at Capital University of Economics and Business, said delayed retirement “needs to be coordinated with industrial policies”.

Extending the employment years of Chinese workers has become an inevitable policy choice to address the problem of an ageing nation. However, the fundamental solution lies in tackling the issues of ageing and low birth rates, and alleviating the population imbalance crisis. Boosting the birth rate, infusing society with new blood and nurturing new labour forces have become essential policy priorities.

The reform plan of the third plenum also pledged to build a “childbirth-friendly society” by bringing down the costs of childbirth, parenting and education.

Song Jian, a professor at the Population and Development Research Center at Renmin University of China in Beijing, said a “childbirth-friendly society” should extend the focus beyond childbirth to support the entire reproductive-age population, particularly women. He said creating such a society is a collective task and a public welfare project.

Supportive fertility policies and incentives are key to addressing this issue. Since 2021, various strategies have sought to help families with the costs of raising children. These include preferential housing policies for families with multiple children, developing childcare institutions, providing parental leave and increasing individual tax deductions. Additionally, more than 30 regions have introduced fertility subsidy policies, according to Caixin’s calculation based on public information.

As the cost of raising children continues to rise, having children is no longer just an individual choice. The government plays an increasingly important role in encouraging childbirth and supporting parenting and creating a childbirth-friendly society is a comprehensive social undertaking, an analyst said.

“A childbirth-friendly society depends on the entire social environment,” said Lu at Peking University. “It involves not only care, education and fertility but also employment and medical insurance, encompassing the entire lifecycle.”

This article was first published by Caixin Global as “Cover Story: China Moves to Raise Retirement Age to Bolster Workforce, Ease Pension Pressure”. Caixin Global is one of the most respected sources for macroeconomic, financial and business news and information about China.

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)