A Foochow coffee boy’s journey through Singapore’s kopitiam history

At 12, Choo Ee Choo came to Singapore from Fuzhou and began life as a kopi kia in Balestier. Now 80, he recalls a time when brewing coffee was a guarded craft, and the Foochow Coffee Restaurant and Bar Merchants Association helped settle disputes and support the community. For Choo, coffee wasn’t just a drink — it was a way of life, even for the poorest coolies with only half a cup to spare. Lianhe Zaobao lifestyle correspondent Tang Ai Wei finds out more.

At around 12 or 13 years old, Choo Ee Choo, 80, came to Singapore from Fuzhou to join his fellow countrymen who had already come. He worked as a “coffee boy” (kopi kia in Hokkien, meaning coffee server) in the Balestier area, earning between S$20 and S$30 a month.

He told Lianhe Zaobao, “I was doing all the random jobs — everything no one else wanted to do. One of them was delivering coffee to a dozen stores. The timing had to be just right, too, when the store owners were actually there. If I offended them and we lost these long-time customers, I would get scolded by the boss.”

In 1964, Choo took over a drinks stall in the cafeteria on the second floor of the Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce Building on Hill Street. Although he became a small business owner, he still had to continue serving coffee. He recounted, “The building had eight floors, and the lift attendant wouldn’t let me use the lift, as they were afraid that I’d dirty it. So I had to take the stairs. Back then, I was still young and strong, and I didn’t mind the hard work to earn money.”

Choo then became a shareholder of Oasis Taiwan Porridge in 1968, and only retired after the restaurant moved to Toa Payoh in 2008.

Power of a promise

Although no longer running a coffee stall, Choo still cares very much about his peers. He joined the Foochow Coffee Restaurant and Bar Merchants Association in the 1970s and served in various roles on the executive committee. He later took on the role of arbitrator, a position he holds to this day.

“Young people nowadays insist on seeing everything in black and white, and they turn to lawyers for everything. The association’s function in this regard has gradually weakened.” — Choo Ee Choo

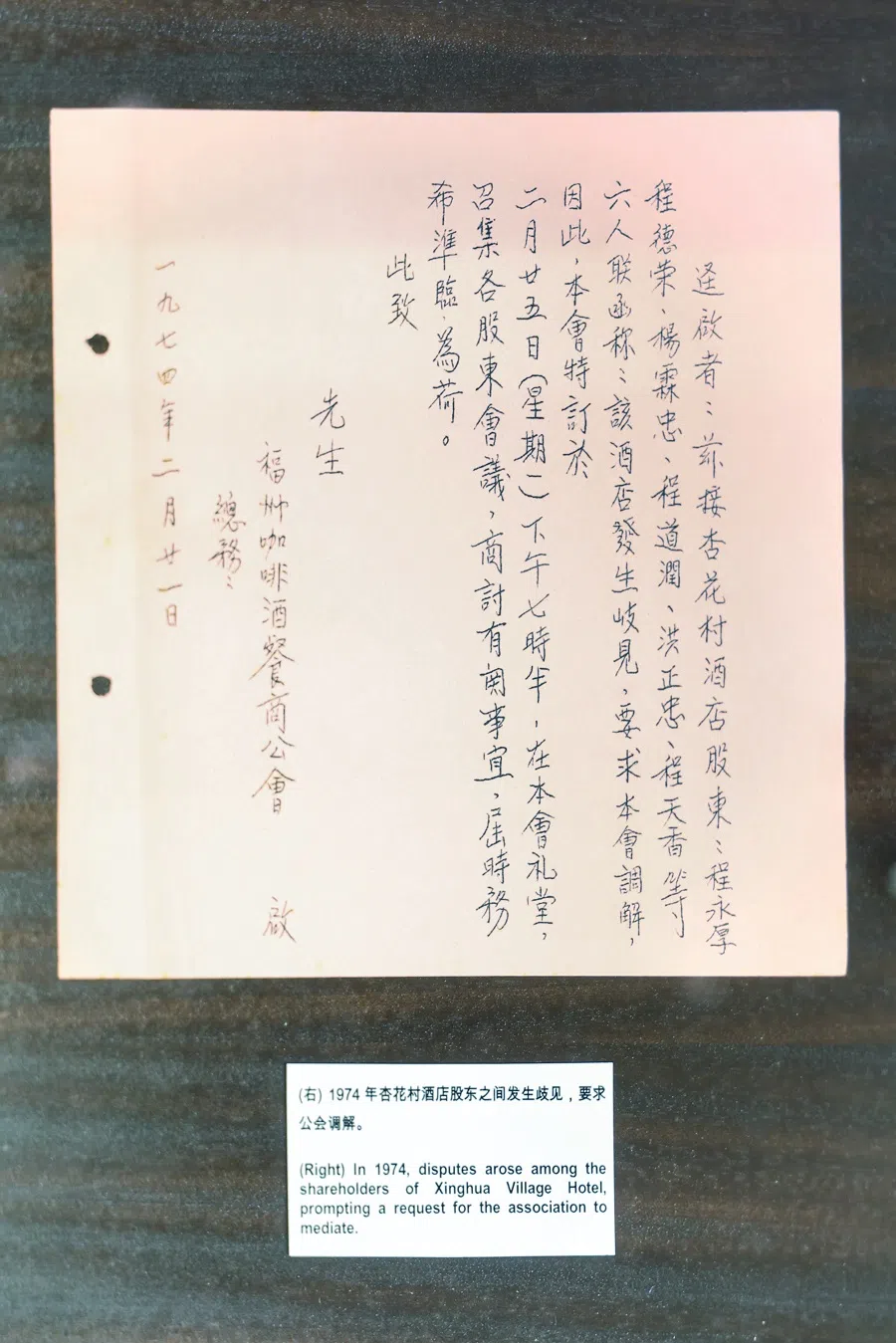

The role of arbitrator feels like a relic of a bygone era. Choo explained, “Back in the day, the association had a lot of respect from its members. Hiring a lawyer wasn’t cheap, so people would just go to the association when they needed something notarised. Like, if a coffee shop had a few different owners, they’d ask the association to help sort out the share distribution and make it official. And if there were any fights over profits, they’d call in the association’s arbitrators to help settle things.

When our forefathers journeyed to Southeast Asia from China, they had very strong bonds of loyalty and trust, and a verbal agreement was as good as a written contract. Choo lamented, “But what their fathers promised back then, their sons don’t necessarily acknowledge today. Young people nowadays insist on seeing everything in black and white, and they turn to lawyers for everything. The association’s function in this regard has gradually weakened.”

Coffee from the heart

Within the Singapore Coffee Shop Heritage Gallery, several precious handwritten documents from the Foochow Coffee Restaurant and Bar Merchants Association are on display. There is also an 80-year-old signboard of the “Kiew Heng (侨兴)” coffee shop, a donation from Choo. Kiew Heng was the name of his father-in-law’s coffee shop, located near Whampoa market. It closed its doors about 20 years ago. Choo also donated four 1-cent coins from the 1920s.

He said, “The Foochow people are very frugal. They would place two coins in the water boiler. When the water boiled, the coins would clink. Hearing this, they would remove the firewood, saving fuel and preventing the water from evaporating.”

“Brewing coffee isn’t just about using boiling water, good coffee powder and pouring the right amount of milk. The most important thing is the heart — remembering each customer’s preferences.” — Choo

In the past, head brewers guarded their craft closely. As a kopi kia, Choo did not get to touch a coffee pot until three years later, when he finally got the opportunity to brew coffee for half a day. He said, “Brewing coffee isn’t just about using boiling water, good coffee powder and pouring the right amount of milk. The most important thing is the heart — remembering each customer’s preferences. Some like it weak, some like it strong. If a different brewer makes the coffee, the customer might find it unsatisfactory because it doesn’t suit their taste.”

A glistening set of old copper coffee pots that sits in the heritage gallery holds special significance. Choo explained, “In the past, working in a coffee shop was considered a bottom-rung job. Now, running a coffee shop has entered a golden age, and holding a coffee pot is like holding a golden rice bowl.”

Singapore’s first coffee shop heritage gallery

The Singapore Coffee Shop Heritage Gallery is located on the fourth floor of the Foochow Building at 21 Tyrwhitt Road, within the premises of the Foochow Coffee Restaurant and Bar Merchants Association. It is open from 10 am to 5 pm on weekdays, and is free for the public to visit.

Coffee shop owners would sell them half a cup of coffee, even allowing them to buy on credit. To this end, they made miniature coffee cups — half the size of regular cups — but filled them to the brim.

Sherry Lim, curator of the Singapore Coffee Shop Heritage Gallery, shares some interesting historical facts.

More Foochow coffee shop operators than Hainanese operators

Hainanese and Foochow immigrants arrived in Singapore relatively late and were often relegated to marginal service industries. In 1927, there were 195 coffee shops run by Hainanese. After World War II, the Foochow community overtook them, dominating the industry. By 1950, there were over 2,000 coffee shops in Singapore operated by Foochow and Hainanese immigrants.

Named after plantations

Early vendors would push their drink carts to plantations (园 yuan, lit, “park” or “garden”) to sell drinks there. When they were finally able to open their own coffee shops, they named them after these plantations. Later coffee shops followed suit, adopting the “XX Yuan” naming convention, such as Sheng Ping Yuan (升平园), Bin Zhen Yuan (滨珍园), Jing Xing Yuan (景星园), and Le Tian Yuan (乐天园).

Half a cup of coffee

One of the display cases in the heritage gallery features smaller coffee cups. In the early 1920s, coolies earned meagre wages, and some who smoked opium would add butter to their coffee to soothe their throats. Coffee shop owners would sell them half a cup of coffee, even allowing them to buy on credit. To this end, they made miniature coffee cups — half the size of regular cups — but filled them to the brim.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “从咖啡仔到仲裁员 见证行业苦尽甘来”.